Glory Daze, the region’s annual extravaganza of vintage and custom motorcycles, is moving. This year’s show will take place Sept. 21, and it will be hosted by Pittsburgh Brewing Company.

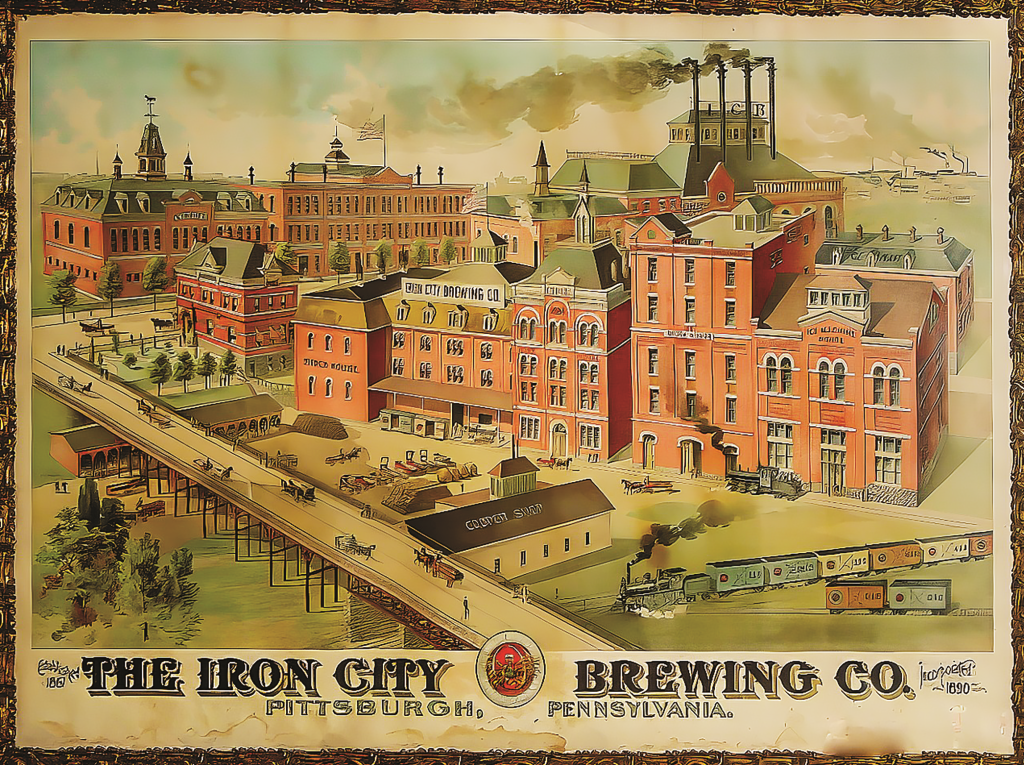

Wait, what? An event that draws up to 10,000 people is occurring at a brewery? Where they make Iron City and I.C. Light? Strange as it seems, Pittsburgh Brewing, with 42 acres of green expanse along the Allegheny River at Creighton, is an up-and-coming venue for live performances and celebrations of all types. Clearly, this is not your father’s Pittsburgh Brewing, a company that once dominated its segment regionally but that flirted with failure for much of this century. And while live events are an effective marketing tool for the new-look Pittsburgh Brewing, the more important takeaway is that the company is thriving, regaining market share and relevance once again.. Pittsburgh Brewing traces its roots to its 1861 founding by a German immigrant named Edward Frauenheim. Through organic growth and mergers, the company expanded and became a Pittsburgh institution; its historic Lawrenceville plant spanned more than 20 buildings, and Iron City became the first name of beers in the region.

But as industry heavyweights invaded the space, sales of I.C. Light dropped dramatically; according to the company, I.C. Light market share regionally plunged from 75 percent to 3 percent. Pittsburgh Brewing was ill equipped to respond in its antiquated, inefficient plant. In 2009, the company began outsourcing its brewing to the old Rolling Rock plant in Latrobe, a desperate money-saving ploy. That came amid a series of six ownership changes, yet none of those new teams could get black ink flowing.

Enter Cliff Forrest, a North Hills native and career-long entrepreneur who was seeking to diversify from the coal mining business where he’d been successful.

“Being a born and raised Pittsburgher and being a bit of a history buff of our region, I thought there wouldn’t be anything cooler than being a part of Pittsburgh Brewing,” Forrest says. “You talk about iconic! There can’t be too many companies with the history of Pittsburgh Brewing. So it was enticing from that perspective.

“The folks that had been advising me said, ‘This is the dumbest investment you ever made.’ There are things I do that are not completely profit motivated.”

The acquisition occurred in phases. First, Forrest bought the intellectual rights to such things as brands and recipes. Next was the question of the old Lawrenceville plant.

“The dream was to rebuild the brewery back in Lawrenceville as it was in 2009,” Forrest recalls. “We got an estimate at what it would cost, and it was crazy expensive.”

As luck would have it, Forrest had just purchased a property in Creighton that was the first glass plant PPG built in 1883. The plant was sold by PPG to Pittsburgh Glass Works, which made automobile windshields but was shut down in 2018 due to a smoldering fire under a portion of the glass factory. Long ago, PPG had used coal from their mine adjacent to the plant in the glass-making process. Later PPG built buildings over the area used to store the coal. After 50 years, the residue of the old coal pile started to spontaneously combust, making the buildings unsafe. In 2019, Forrest bought the site as a true fire-sale — literally — of just more than $1 million. With his mining experience, Forrest razed the buildings, doused the coal fires, and was ready to convert the site to the new Pittsburgh Brewing.

Forrest won’t say what he’s spent renovating the property — “I don’t want my wife to know” — though he does allow that he invested more than $3 million on new slate roofs to protect some of the old brewery buildings in Lawrenceville. One of the buildings houses the controller’s office, which has served as the Pittsburgh Brewing office continuously since the 1870’s. The other buildings will eventually be a brew pub and restaurant. Whatever the cost, the new brewery is a marvel, all functions laid out logically and efficiently.

And the beer is relevant again. The new brewery retired several of its workhorse brands, including American and American Light, which together accounted for 17 percent of sales. Even with that big hole to fill, sales in 2023 grew to 119,000 barrels, up from 90,000.At the heart of this success are several factors. Forrest credits his employees. Beyond that, are automation and ensuing increases in efficiency; product diversification and new partnerships; innovative marketing highlighted by on-site events (see sidebar), and the entrepreneurial spirit of Forrest, a risk taker but not a micro-manager.

“As state-of-the-art as you can build”

In traditional depictions of large-scale brewing, technicians in white lab coats climb tall ladders to reach the top of ginormous vessels, there to dip thermometers and such into the bubbly mix. There’s very little of that at the new Pittsburgh Brewing, where a casually dressed brew team makes most adjustments by computer.

“There are so many sensors and alarms,” says Mike Carota, who grew up in Latrobe across the street from the Rolling Rock plant, used his degree in chemistry to land a job with Pittsburgh Brewing right out of college, survived all the ownership changes and now serves as the company’s brewmaster. “If something doesn’t adhere to the software program, the system lets us know.”

That’s just one component of the automation that marks the re-imagined Pittsburgh Brewing.

“We could have gone out and bought used brewing equipment and cobbled this thing together for probably a third of what we invested here,” Forrest says. “But what we have is, from a brewing point of view, as state of the art as you can build.”

Another example is the brewery’s filling machine. Not only can the filler pour beer into any sized can but, with a quick changeover, it also can fill bottles. Filling typically requires separate lines for cans and bottles, which means higher costs and longer fill times. To beat that, Pittsburgh Brewing sourced its dual filler in Slovenia through the German company that designed the brewery. Forrest is proud that all of the construction was done by local workers.

Significant, too, is headcount, which back in Lawrenceville’s heyday totaled over 200. Today, that number stands at 41, including all production and sales staff, although some functions are outsourced. Still, it’s a lean operation.

That efficiency can be seen in a number of metrics. Where the old brewery used up to nine gallons of water for every gallon of beer, the new brewery has cut that ratio to 3-1. The company also has reduced can wastage dramatically. In Lawrenceville, the wastage rate was about 10 percent. Now, it’s negligible. Notes Forrest: “The fellow that took the scrap out of Latrobe wanted to come here and get our scrap, so he put in a bin. But our wastage is, like, .4 percent. The guy said, ‘I’m wasting money here.’ He came and removed his bin.”

New brews, new partnerships

Pittsburgh Brewing has tried to regain market share in a number of ways, including diversifying its product line. It carried over a number of products, such as Old German, Block House and I.C. Light Mango; the latter premiered in 2011 and now accounts for sales of more than 100,000 cases annually. The company also freshened its product mix.

“It starts with marketing and their research,” Carota says about the selection process for new beers. “You don’t develop an idea and ask Marketing, ‘Can you do something with this?’ It’s the other way around.”

Among the new family members: Block House Pumpkin; Block House Double Chocolate Block; Block House Poolside. The company partnered with Dancing Gnome, a Sharpsburg craft brewery, to produce Robin Hood Cream Ale, and it collaborated with Giant Eagle and Food21, a nonprofit that promotes the local food economy, on Harvest PA Helles Lager. If you’ve never heard of these brews, it may be because Pittsburgh Brewing narrowly targets its advertising for limited releases.

“A lot of marketing is through social media and billboards; those are the areas in which we play,” says Todd Zwicker, company president. “We don’t necessarily do common or similar media. We do more grassroots. That definitely plays with our brands.”

Such limited releases have helped Pittsburgh Brewing attract new customers and, at the same time, form new partnerships within the industry and the community.

To keep the innovations coming, the company has created a small-batch brew house, capacity 10 barrels, to enable it to experiment with potential new releases without committing large-scale resources. And it’s added a distillery, where branded rye, bourbon and single-malt whiskey are aging until they’re ready for release.

“The staff gave me a barrel of the bourbon as a Christmas present,” Forrest says. “It’s only seven months old, but it’s aging very well.”

A 20-to-30-year plan

For all that, if Pittsburgh Brewing is to continue its success, the most important factor likely will be the entrepreneurial spirit of Forrest, who has little use for standard corporate governance. The company, for example, has no board of directors and files no annual reports.

“One thing that’s nice when you’re a sole owner — we can make decisions very quickly,” he says.

Forrest’s drive to own and operate businesses wasn’t immediately apparent, as he studied mining engineering at Pitt before dropping out to pursue an unusual opportunity. His brother-in-law, George Romero, the late, acclaimed zombie film master, was making Dawn of the Dead and offered Forrest the job of grip, the guy who schleps cameras around. Forrest accepted and, as a reward, Romero allowed him to appear on camera with the film’s opening lines: “You all right? Shit’s really hit the fan.” Despite that spectacular cinematic debut, coal mining soon beckoned.

“My father had been in the coal business,” Forrest says. “He lost the company, went broke when I was about 12 years old. That was my burning desire, to get back in the coal business.”

He started as a coal broker and, still in his early 20s, had the chance to start up a mine. He took that chance, and the mine became the foundation for Kittanning-based Rosebud Mining, which Forrest has grown into the third largest deep mining company in Pennsylvania, according to industry data. Over the years, he’s acquired other business interests, including:

-Chemstream Inc., a water treatment company headquartered in Indiana County.

-Pennsylvania General Energy Co., a Warren, PA, natural gas producer.

-Oberg Industries, a well established, highly regarded business, based in Freeport, that provides machined and stamped metal components.

-The Lodge at Glendorn, a Bradford Relais & Châteaux that Forrest describes as a “boutique lodge” offering cabins as well as fishing, hunting and hiking amenities. Forrest stayed there once, liked it and bought the joint.

Although these businesses have thrived, that can’t be said about every enterprise in the Forrest empire. One, in fact, was a complete disaster. That would be Freedom Industries, a chemical supplier in Charleston, WV. Practically before the ink was dry on Forrest’s 2013 acquisition, investigators discovered that a foul-smelling substance was leaking into the Elk River from Freedom’s storage tanks, threatening to contaminate the public drinking water supply. The culprit turned out to be malodorous but not toxic — “Not one guppy died,” Forrest insists — and the leak was attributed to the company’s previous management. Two of them were convicted on various charges; the former company president was sentenced to 60 days in jail.

Freedom Industries soon was bankrupt. Though Forrest and his team were blameless, the incident represents the sort of debacle that can befall entrepreneurs. Yet where Pittsburgh Brewing is concerned, the tap is always open.

“What I hope over time is that people will have an opportunity to try our beer,” Forrest says. “Western Pennsylvanians generally are pretty loyal. Someday, someone will say, ‘Why in the hell am I drinking a Milwaukee beer? I should be drinking our local production.’ It’s a treasure to western Pennsylvania, what we’ve built here.

“It’s a ground game for sure: two yards forward, one yard back, maybe two yards back. I look at this as a 20-to-30-year type of plan . . . This is something that I hope is in multiple generations of my family.”