Pittsburgh’s Gentleman Scholar

I wasn’t sure when i knocked on the door that I was really at the right house. I thought I had the correct address, but it had been a long trip. I took the passenger ferry to Martha’s Vineyard and then rode my bicycle 10 miles out to West Tisbury. And then I had to hunt around the neighborhood for a bit. When an attractive, smiling woman answered the door, that was a good sign. She didn’t even ask me my name, but cheerfully ushered me into the family kitchen. And I knew I was in the right place when the beaming, avuncular visage of David McCullough appeared in the room, joining me and his wife Rosalee for lunch.

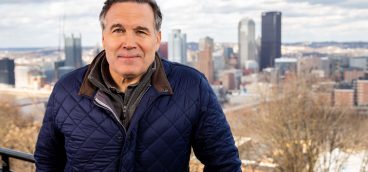

I had met David 10 years earlier when he came to Pittsburgh to give the keynote address to the inaugural meeting of the Riverlife Task Force, the group that would help transform Pittsburgh into its new-urbanist 21st century renaissance. That was back in 1999, when Pittsburgh was still emerging from the recession it suffered from the loss of heavy industry in the last 20 years of the past century. I was working on behalf of The Heinz Endowments and other area foundations to organize Riverlife as a strategy to use the city’s 36 miles of waterfront as an urban-renewal catalyst. One of my assignments was to ask McCullough, a native Pittsburgher and America’s leading writer of history, to be the speaker who would set the direction for the work of the task force.

He did that in the most powerful, eloquent evocation of Pittsburgh’s character, coupled with a compelling vision of the city’s potential for an exciting future. In the 23 years since, Riverlife’s execution of an ambitious master plan for the city’s waterfront has become a principal ingredient in the city’s 21st century renewal, resulting in $130 million in direct riverfront investment and as much as $2 billion in indirect economic benefit.

The clarity of purpose for Riverlife was set in those early remarks by McCullough, who grew up in Pittsburgh’s East End and remained devoted to the city ever after:

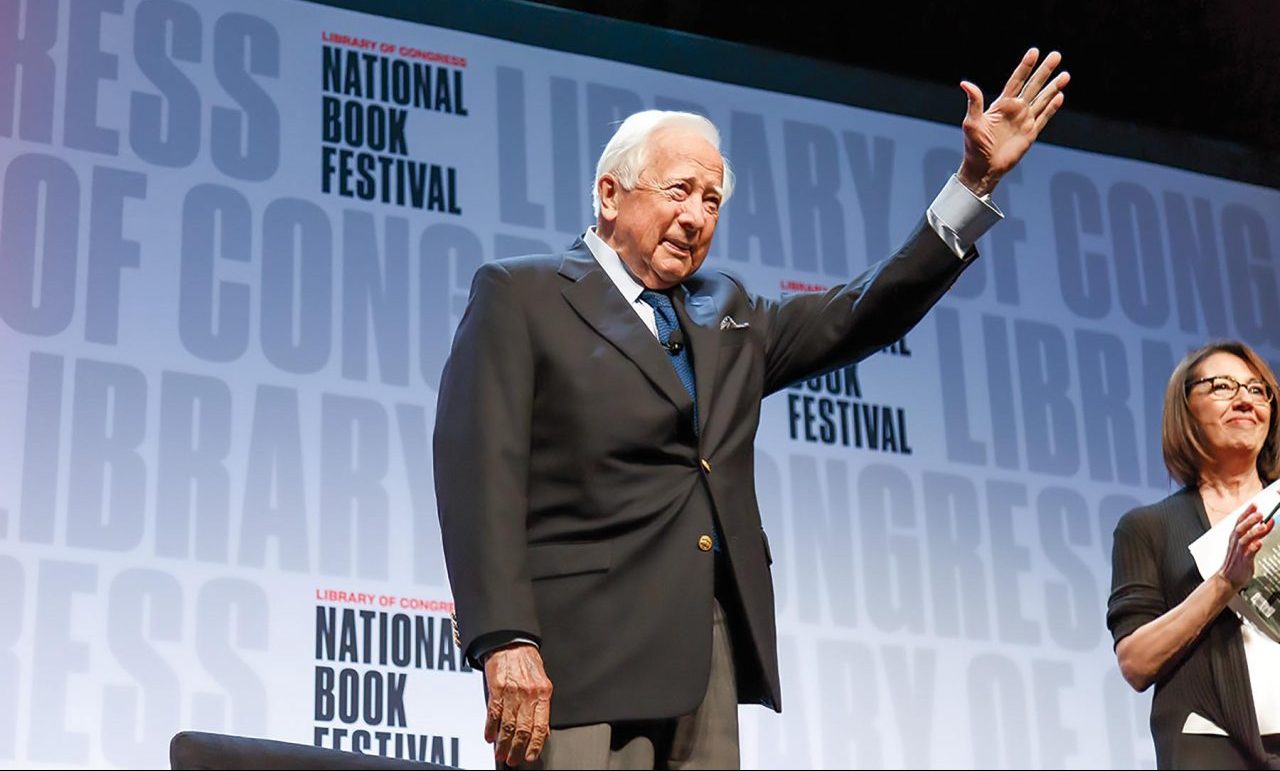

“I think this is an opportunity such as no city in the country has. And I think that it isn’t just a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity — it’s a once-in-a-century opportunity,” he told the hundreds of Riverlife supporters gathered on a tour boat in the middle of the Ohio River, the city’s lighted skyline framing him at the podium.

“What can be done can change the character of the city, can improve the good life in the city for at least another century. And that’s a terrific, thrilling chance. It’s also a tremendous responsibility . . . And don’t make it like other places, because Pittsburgh was never, ever like other places. Make it a place where people want to bring those they love — their children, their family from some other place, some other city, to live here. Make it a place for music and sunshine and trees by the water. Make it possible to walk out of an office building down to the river, or to bring your family to a picnic by the river . . . But think of it on as large, as ambitious, a scale as you possibly can. And build for the long run, not for what’s going to work next week or next year — the long run. And make it in keeping with the city’s heroic past.”

As McCullough became famous in the last half-century as a great writer of history and biography — two Pulitzer Prizes, two National Book Awards and the Presidential Medal of Freedom — he remained devoted to the well-being of his hometown. In addition to kicking off Riverlife, he was instrumental in the organization and development of the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh and the Johnstown Area Heritage Association. Over the years, he came back to town frequently. Occasionally, when he did, he asked me to have lunch to talk about ideas he wanted the regional foundations to focus on. Mostly, he was concerned about public education — sometimes despairing of the fact that most American high school students knew little American history and almost no world geography.

Typically, when we were having lunch, other people would come over to the table to say hello and express their appreciation for McCullough’s work. Always, he was modest: unfailingly polite and considerate. Like that other Pittsburgh hero of humility, Fred Rogers, McCullough would steer the conversation to the person with whom he was speaking, intent on learning about that person’s life in western Pennsylvania.

In addition to this graciousness of character, he was exceptionally generous with his time and his thinking. That is how I ended up at lunch with David and Rosalee some 10 years after the Riverlife kickoff: He agreed to give me an afternoon of free advice on writing a biography.

When I was at the Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at St. Vincent College in 2010, the subject of a biography of Mister Rogers came up, since there had never been a full-length life-history of the great educator and television creator. Joanne Rogers suggested I call David McCullough and ask him to write it. When he explained that, although he liked the idea, he couldn’t do it because he had a long list of projects underway, he suggested I should take it on. When Joanne endorsed the idea, I decided to do it. But I had never written anything longer than a magazine piece, and I asked McCullough for help. Hearing that I was staying nearby in Massachusetts, he asked me to come to West Tisbury for an afternoon tutorial.

Before lunch, he invited me out back to see his writing shed on the edge of an open field. Inside: no computer, no printer, no telephone, no technology whatsoever. Just a 1940s Royal typewriter, a stack of writing paper, a paste pot and a pair of scissors. I asked him if it wouldn’t be easier to use a computer to move text around. “I don’t want easier,” he said. “I want to take my time.” There were no screens on the windows of the little hut, all of which were open. “David,” I said, “don’t the flies fly in?” Opening his arms wide, he said: “The flies fly in . . . and the flies fly out.”

A great deal of what David McCullough wrote was fashioned in that little hut. All of it was written on that ancient, second-hand Royal. His first editor and most important critic was Rosalee. They would read his texts aloud to each other; she would comment, and he would correct.

McCullough gave me a wealth of good advice for a writer. Two things stand out:

First off, he said: start writing right away. When I told him I thought I would do two or three years of research and then start writing, he said, “Wrong. You have to start writing now, and keep on writing the whole time while you do your research.”

According to McCullough, the act of writing, early on, would shape the research in positive ways. “It doesn’t matter what you write, or where it fits in the book, or even whether it finally fits in the book. Just write. You’ll ask better questions and do sharper research if you’re writing.”

Secondly, range far and wide in your inquiry and do not be constrained by any preconceptions about your story. “If you are working on your field of research and an interesting tangential question comes up, follow it,” he said. “Follow it right off the field and into the woods and go as far as it seems interesting. You can figure out later what to do with it.”

McCullough’s counsel about writing improved my books immeasurably. Just as important, it made the process much more fun. That was another piece of advice I got from him: Make sure you are having a great time writing your book, and it will be the better for it.

One of the last honors McCullough achieved in his life was the renaming of Pittsburgh’s 16th Street Bridge as the “David McCullough Bridge” in 2013. Said the author: “I’ve had many honors that mean a great deal to me . . . But no pat on the back has ever touched me to the heart, to the depths of what I am, the way this announcement of a bridge named in my honor has.” And he acknowledged that, for a man who made so many connections — for his readers and for his hometown — the bridge was the perfect symbol. He died on Aug. 7 of this year at his home in Hingham, Mass.