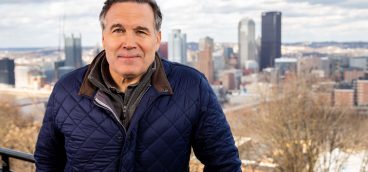

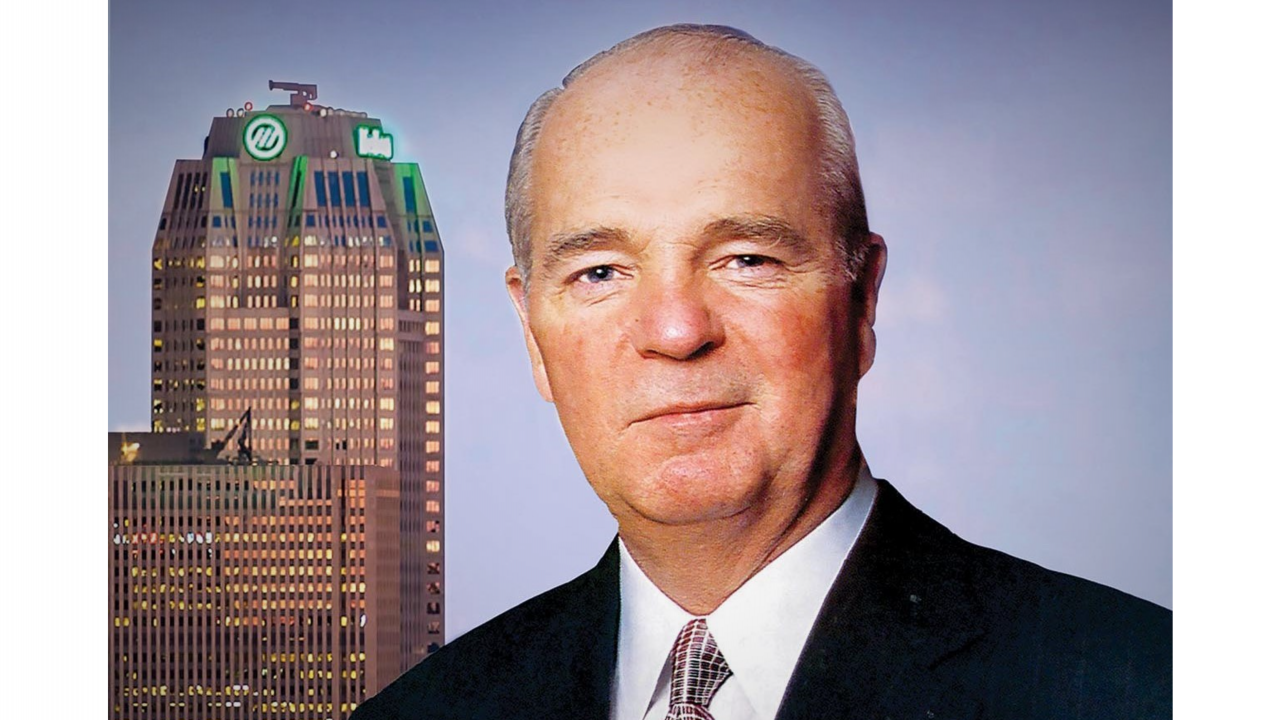

Editor’s Note: This article is based on the upcoming book published by Lyons Press:

“From Swampoodle to Mellon Bank CEO; An Irish American’s Journey, the Autobiography of Martin G. McGuinn Jr.”

When I came to Mellon Bank in 1981, it was the dominant bank in Pittsburgh, much to the chagrin of Pittsburgh National Bank, which later, through expansions, became PNC. When I arrived, Pittsburgh National was very envious of Mellon’s business and its reputation, so there was a real rivalry, although not on Mellon’s part in those days. People wondered how long PNC would survive on its own. Ironically, it was Mellon that ultimately was sold and PNC became one of the nation’s biggest banks. This is my account of how and why Mellon was sold.

By the time I became CEO in 1999, I had been general counsel and built a captive law firm with 125 in-house lawyers. I’d run many of the bank’s biggest operations: retail, credit card, mortgage servicing, cash management, real estate, strategic planning, marketing, communications, and community and government relations. Mellon was on solid footing, having come back, under Frank Cahouet’s leadership from near bankruptcy in 1987 after a collapse in oil prices spilled into real estate and caused Mellon to report a $60 million loss in one quarter. Cahouet was then brought in and he fired almost 4,000 of Mellon’s 18,000 employees. He was difficult and demanding to say the least, but he did what was necessary to save the bank. The Cahouet years saw a great deal of success. He was CEO during what had been until that point the biggest economic expansion in U.S. history and one of the greatest bull markets of all time. And he oversaw our purchase of Dreyfus and The Boston Company and our expansion of wealth management. But by the end of his tenure, the bank had stalled, and because of his harsh personal style, other companies had no interest in merging with or being purchased by Mellon. Employee morale was low.

In a February 1998 board announcement, I became CEO- elect, with Cahouet retaining the title until the following January. In the organization, the news of the succession was received well. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette had my picture on the front page, and the article said there was a new “affable” CEO at Mellon, and this was going to be a change. One newspaper said it was going to be a “kinder and gentler” leadership at Mellon. I was 55. At that time, Mellon had about 20,000 employees, with 12,000 of them in Western Pennsylvania.

In April of 1998, Tom Renyi, the CEO of Bank of New York, called. We had considered merging with them years before but didn’t because it became clear that our cultures were too different and that it would not really be a merger of equals. Renyi told me, “We would like to re-ignite our talks, but this time we’d like to acquire you.” I said we weren’t interested and issued a press release: “Mellon not for sale.” Then Renyi announced a hostile takeover attempt, and we had to fight them off. Our defense against Bank of New York was all-out warfare. We had gotten to know BNY pretty well in the previous negotiations. It wasn’t a fit, culturally or otherwise. A few months later, BNY withdrew its hostile offer after they realized they could not win the shareholder vote.

A NEW MELLON

Our new leadership team included Kip Condron, Steve Elliott and me, and on Jan. 1, 1999, we hit the ground running. We immediately announced a name change from Mellon Bank Corporation to Mellon Financial Corporation. We wanted to signal that things were going to be different, that Mellon was not a traditional bank, and this was going to lead up to many changes. Our strategy was to invest more in the faster growing businesses such as asset management and asset servicing.

In our first year, we produced record earnings. We had $2.7 trillion in assets under management, administration or custody, including $488 billion under management. We were the leading bank manager of mutual funds. We were off to a good start.

One of the first things we did that first year was to announce “The Employer of Choice” program. Morale was really bad, and I wanted to let the employees know immediately that we intended to change this by investing more in them.

In his first five years, Cahouet, appropriately, had focused on restructuring the company by laying off employees and cutting expenses. The problem was, he never gave up doing that. It just turned out to be his nature. Even when the company was growing and doing well, he was still micromanaging, cutting expenses and reducing staff levels, cutting salaries, and forcing people to work long hours sometimes unnecessarily.

I truly believe that you get a lot more with sugar than you do with vinegar. And I traveled to all of our major offices around the world to conduct what I called a “listening tour.” I met with employees to find out what was working, what wasn’t and what could we do better.

The former Mellon Bank headquarters building at Smithfield Street, between

Oliver and Fifth avenues, which later housed the Lord and Taylor department

store

We wanted to have strong employee benefits. We were one of the first employers to provide domestic partner benefits. And we made changes to the merit increase approval process and salary increases for promotion. We gave every employee stock options and this included everybody, all the way down to part-time workers. The overall idea was “You’re an owner of the company. Think like an owner. And we’re going to all succeed together.”

We also started what we called a Customer Focus Initiative. The idea was, you’re always thinking about the customer. That was everybody’s job whether they were facing the customer on the front line or in the back office providing support. It was a big change, and to some degree it also was different culturally for Pittsburgh, which unlike many other cities, had never been a service-oriented city. In Pittsburgh, people had traditionally been in the steel business and other primary industries where the customers often came to you. Our theory was if we took care of our employees, they would take care of our customers. And if we took care of our customers, we were going to grow and succeed.

SELLING THE RETAIL BANK

In early 2001, carrying through with this notion that we were a financial services company and not a traditional bank, we made a big change. We agreed to sell our retail bank branches. From the beginning, we tried to send a signal when we changed the name from Mellon Bank to Mellon Financial Corporation. We weren’t looking to sell the retail bank at that point. But we were definitely thinking of emphasizing the higher growth businesses. So now, selling retail seemed to be the logical strategic evolution.

We were narrowing Mellon’s strategic focus so that we could be more of an asset manager and asset servicer and be in higher growth and higher return businesses. We kept the wholesale bank business for those corporations where we managed their pensions and had custody of their assets. So we would be left with corporate lending, cash management, all the asset managers, asset servicing, and the private banking and trust business.

After we announced it, Cahouet (who was no longer on the board) used a friend of his to call each one of the directors and tell them to vote against it. He didn’t tell me; I heard it from the other directors. I told the directors, “We think it’s the right thing to do. We’re going to present it to you, and we’ll answer all your questions and then the board will vote on it.” The board unanimously approved it in June 2001.

The deal closed that December. Mellon had been in the retail business since the 1940s, and it was a big community brand. People in the community didn’t know our corporate bankers; they knew retail. So it was a bold move, to say the least. With the sale, we also cut our dividend, which was very unpopular with a lot of people particularly in the Pittsburgh area, where Mellon investors were like “coupon clippers” and counted on that dividend.

We had to cut the dividend because if you’re in higher growth, higher return businesses, those businesses pay lower dividends so that you can invest more in the businesses. We knew we’d take some lumps on the dividend and we did, but not more than expected. I probably could have explained it better. But the move was also unpopular in Pittsburgh because we had all these branches, branch employees and support people, and they were, in effect, being sold — thousands of people. So it had a lot of emotional repercussions.

We were cutting a lot of expense and revenues as well. But we were getting paid $2 billion for the retail bank too. The premium was about 17 percent, which was one of the highest in banking industry history for similar transactions. And we insisted that the sales contract required Citizens, the buyer, to retain all the employees.

FALLING MARKETS

All of these moves in the first two and a half years were designed to improve morale, make us customer-oriented and position the company for future growth and faster growth. We felt the pieces were in place for a very successful future, and our share price in the 40s reflected that. Sometimes, however, despite your best efforts, events occur over which you have little or no control but which affect your fortunes and, in this case, the fortunes of the company. Sometimes luck, good or bad, plays a role.

The markets were an example of that. When the terrorist attacks struck on Sept. 11, 2001, the markets fell 14 percent, continuing a downward trend that had begun when the speculative dot-com bubble had burst in late 2000. But the decline in stocks was a grinding and continuing process that lasted a couple of years and became one of the worst equity markets since the Depression. From 1988-1998, the S&P 500 had a huge average annual increase of 16.5 percent. During my seven years, though, the S&P 500 increased by an average of only 1.6 percent a year — significantly below the historical average of about 10 percent a year and one-tenth of the unparalleled increases during Cahouet’s time.

The troubled markets were a problem because this was our business now — asset management and the complementary asset servicing which involved all the back office functions — the reports to investors about transactions, stock prices and how their accounts were doing. It was a big business, but the market decline did two things. First, it hurt our business. We got paid in most of our asset management business by the value of the account. We got a percentage of that account value for each quarter and year. And so to the extent that that value declined, we were paid less revenues and profits. The negative impact on our profits went on for several years. And the second thing was that it was impacting our stock price too.

TROUBLE BREWING

By the June 2005 board meeting in Miami, I had been CEO for six and a half years. And at that board meeting, Robert Mehrabian suggested that it was time to start considering finding my successor. The board agreed that we should hire a president and chief operating officer. They said that it would take at least a year to get him or her and then that person would be groomed to succeed me — and that it would provide for a good transition. I would serve until I was 65. On that basis, it was very hard for me to argue against it. I wasn’t aware of it then, but another agenda by several directors was beginning to play out.

At that point, board member Wes Von Schack, the former Duquesne Light CEO who was chair of the Human Resources Committee, said at that June 2005 board meeting, “Why don’t we sell the company?” I told him at the meeting that selling the company wasn’t a strategy. It was throwing in the towel and saying, “We’ll make more money for shareholders by selling it and getting out of the business.” I said, “We can always do that. I don’t think it’s the best course of action.”

In the second, third and fourth quarters of 2005, we beat Wall Street expectations and had excellent earnings. In November of 2005, we had the annual meeting of senior management from all over the world, which was a big success because we had so much momentum and everyone was feeling good about our progress. The stock was up 29 percent from May/June until the end of January. Things were really going great, and in 2005, we were Fortune magazine’s Most Admired Company in our category.

At that time, however, without my knowledge, there was a faction on the board, and Cahouet was driving it (Cahouet, Von Schack, and Ruth Bruch, the CIO of Lucent, all were also on the board of Teledyne led by Mehrabian). I believe their aim was to get me out and to sell Mellon to the Bank of New York.

In November of 2005, I got a call from Rodge Cohen, the lawyer from Sullivan & Cromwell who was a close friend and adviser and who frequently represented Mellon. He was very attuned to the industry and was the dean of all bank lawyers. Rodge said to me, “I’m hearing in the marketplace that the recruiters are telling people that they’re interviewing that they want someone to come in and be CEO immediately.”

Under Andrew Mellon (above), Mellon Bank

arguably became America’s first venture

capitalist. The family’s extraordinary

success has spanned generations and

numerous branches, creating one of the

nation’s largest enduring philanthropies.

So I called up Von Schack and he called back with Mehrabian on the phone and I told them what I was hearing. “Oh no,” they said. “That’s definitely not true. Absolutely not.” Why would they deny that’s what they were doing? Because I could have started to lobby the board and could have done a lot to fight it.

At that point, on the Human Resources Committee were several people, including John Surma, the CEO of U.S. Steel, and Mark Nordenberg, the chancellor of the University of Pittsburgh, Mehrabian, Ruth Bruch, and Ted Kelly, who was CEO of Liberty Mutual Insurance from Boston. I don’t think Surma and Nordenberg were pushing it. The rest of the directors may have known what was going on, but why they went along with this charade, especially later, is still beyond me.

I’ve spoken with a couple of them since then, and one of them said, “Well, I thought we had to defer to the Human Resources Committee.” I told him that all of the directors shared the same fiduciary obligation.

That fall, in 2005, articles started appearing in the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, the city’s secondary, conservative newspaper owned by Richard Mellon Scaife. The Tribune-Review was writing these articles every week saying, “McGuinn should go.” That was the headline. They said I was going to sell Mellon. And they accused me of living in New York. Literally once a week Scaife was doing these articles. And I’d be going down to the Duquesne Club, Downtown and someone would ask, “What’s going on?” People knew Dick Scaife was odd, but his articles were part of several things that were stirring up the waters, and I think that was its purpose. Scaife had gone after Jim Rohr at PNC another time, and Rohr and his board just waited him out until he finally went away.

At that time, our board meetings were becoming fractious. Some people were saying we should speed up the succession process. Some said we shouldn’t. We should do this. We should do that. Candidates were coming in and one of them was Bob Kelly, who ultimately became CEO. I liked him and he was one of the candidates that I recommended, and although I liked him, I said, “You talked about getting someone with operating experience. This guy’s been the chief financial officer. He doesn’t have any operating experience. What are we talking about here? Let’s be honest with ourselves.”

I got another call from Rodge Cohen saying that several board members were pushing this agenda of speeding the hiring up. And at that point, alarms started to go off for me. They should have been exploding by now, but I was still trying to run the bank and believed what the board was officially telling me. In retrospect, you can call it naiveté or stupidity, at least.

FORCED OUT

In January 2006, I went off to Davos, Switzerland, which I’d been doing every year since I was CEO. It was at a ski resort, but I don’t ski. So for me, it was all work and it was good work, filled with business meetings. Two days after I arrived, I was at a dinner hosted by one of our biggest clients, and I got a message saying to call the office immediately.

I excused myself and called. I was told that the board had voted unanimously to hire Bob Kelly and, at his insistence, they made him CEO immediately. They said I had to be out in two weeks.

Holy cow! I was shocked. I heard what they’d said and knew it was a fact, but I couldn’t comprehend it. At that point, I felt I’d been betrayed. But how could the other directors go along with it? I was hurt, but that doesn’t seem strong enough. I was also angry. I felt it was grossly unfair.

Kelly had been at Wachovia in Charlotte. When I later went out to dinner with Kelly to plan the transition, he told me upfront, “I just want you to know I did not ask to be CEO. I was told to say that.” I don’t think the rest of the directors knew that. I think this was the final part in their planned coup, guided by Cahouet. I felt that I’d been stabbed in the back. At the time, it was very emotional. And Mellon was doing very well, including the stock price. In fact, Mellon’s total return to shareholders from Jan. 1, 1999, when I became CEO, until Jan. 27, 2006, the day before my departure was announced, was 23.7 percent. This compares to the increase in the S&P 500 of 16.4 percent. And there was a lot of momentum. Beyond that, here I was, a guy who’d been at Mellon for 25 years and they say to get out in two weeks? Was there no dignity or fairness? Why did the other directors go along? That’s the part I still to this day can’t fathom.

What really added to the hurt was that outsiders and employees might think there was something wrong with the bank. Had there been some fraud committed? Was I a bad person who’d done something illegal or immoral? My reputation was damaged, to say the least. My reputation in the industry had been very strong – I’d chaired the Financial Services Roundtable and been president of the Federal Reserve Advisory Board — and when I was fired, people probably thought, “There must be more that we don’t know. But obviously, it’s bad. If it were good, he wouldn’t be fired.”

In retrospect, should I have been better prepared? Should I have managed the board better? The answers are “yes.” I wasn’t paying enough attention to the board.

Ultimately, it was driven by Cahouet. He wanted to get rid of me partly for revenge — and I think the others went along — but I think in the larger scheme they also wanted to get rid of me so they could sell Mellon. It wasn’t obvious to me until later, but what was really driving this was that Cahouet saw an opportunity. I think he held a grudge against me because he perceived that I pushed him off the board and because I sold the retail bank. And Cahouet enlisted a new ally, Dick Scaife, to join in the effort to move me out.

It was a confluence of many events. Analysts were saying the stock price should be doing better and we should break up the company, and maybe this isn’t the right management to do that because they’re going to be defensive. One big institutional investor — CalPERS — was saying, “Break up the company and get rid of some of the shareholder protections.” And then the Tribune-Review was coming out with weekly attacks.

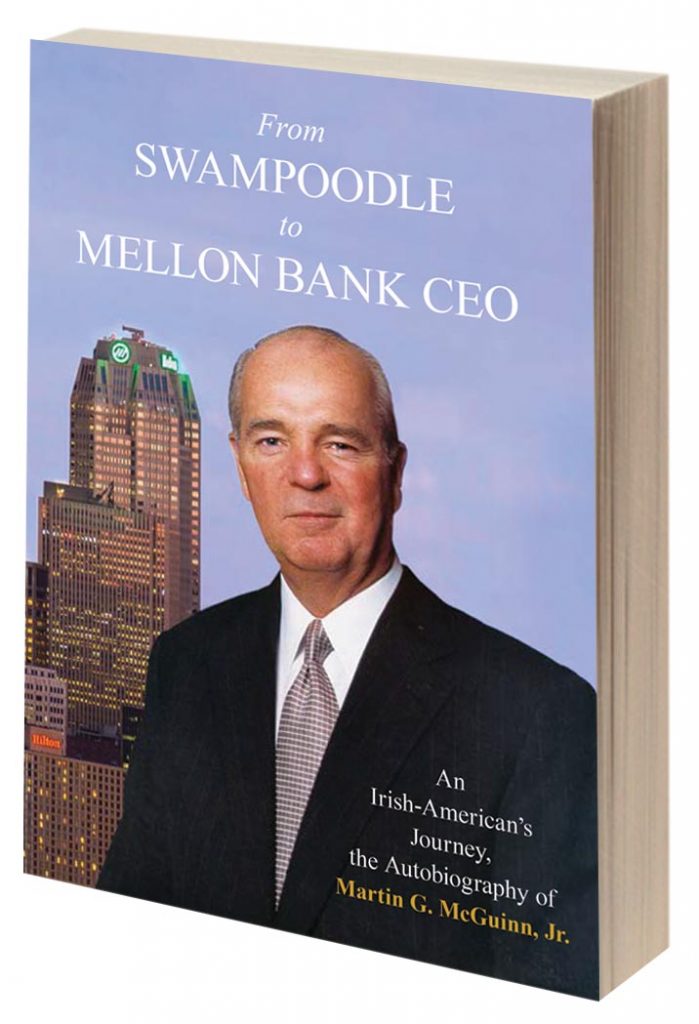

Former CEO Cahouet stopped the financial bleeding and saved Mellon Bank. His

successor believes that years later Cahouet was a major force in the sale of Mellon.

Ultimately, some directors on the board had a separate agenda, so it wasn’t a question of whether our strategy was right or wrong. Cahouet told them: “You’ve got to get rid of McGuinn.” And when they started the search in June 2005, they were committed. Even though that quarter before and the next two quarters after were record quarters, and our stock price was going up. They didn’t back off and say, “Maybe we were wrong – look at the facts.” They were too committed then and the rest of the board sat back and let them drive it. That was the real mistake. That was the part that upset me. I left Feb. 6, 2006 and when the first-quarter earnings came out, they were at a record high.

SELLING OF MELLON

Within three or four months after the Mellon board removed me in January of 2006, it was in negotiations to sell the company to the Bank of New York. The sale was announced Dec. 4, 2006, and it took all that time to negotiate it. I was surprised but not shocked because Bank of New York had been pursuing Mellon literally for decades.

At the surface level, there was an obvious fit. They were two of the four so-called Trust companies. We had sold our retail bank back in 2001, and they sold theirs in 2005. So they were kind of following our strategy, if you will. I’m guessing the initial discussions between Kelly and Renyi went on for at least a month. What was decided was that it was going to be a “merger of equals,” which is almost always a euphemism. Very rarely are the two equal in fact. The reason you do it is so one side doesn’t have to pay the other a premium. In most acquisitions there’s a premium paid.

That’s one of the reasons the acquiree agrees to be acquired. Not only do they think that, by selling, they’ll be better off by not implementing their own strategy, but they’re also getting a pop in the stock.

They hardly ever use the phrase, but legally the phrase is a “change of control.” So before the deal, Mellon shareholders obviously controlled Mellon. With the deal, there was a change of control. That means there were more directors from Bank of New York, more shareholders from Bank of New York, and more senior managers from Bank of New York.

BNY paid a very small premium, which was almost worth nothing. But Kelly got the CEO role, which was an argument for saying it’s more equal, even though he’d been with Mellon for less than a year. It’s been 14 years, and the stock price has done very little. In the same time period, Northern Trust is up by about 73 percent, State Street is actually down slightly, and PNC, Mellon’s former Pittsburgh rival, is up 159 percent.

I was disappointed by the sale. I was interviewed by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette at the time, and I said Mellon didn’t have to be sold. I thought Mellon’s strategy and position were strong and Mellon could do better on its own. After that article, Mellon had a lawyer call me and he said, “If you ever say anything again, we’ll take away your office and see if we can take away your retirement benefits too.”

I think people were surprised by the sale and the fact that it was for little or no premium. But I think people on Wall Street saw the fit. These were two logical competitors who could be stronger together. Now there would be three trust banks, and BNY Mellon would be the biggest. So there was a lot of logic behind it. But the cultures of the two organizations were drastically different and making the “merger” succeed was difficult.

Why didn’t the board fight harder to keep it in Pittsburgh? It’s a little like why didn’t some of them fight harder to keep me in the job? Maybe some didn’t want to jeopardize their board seat. With the merger, the number of directors from Mellon would be reduced in the merged company. The compensation for a director was $200,000 to $250,000 a year, half in cash and half in stock.

The merger took a while to close because it needed regulatory and shareholder approval. But by July 1, the merged company was off and running.

AFTERMATH

It’s amazing how many people — including the man on the street — said to me afterwards, “Why’d you sell Mellon?” That really upset me. All I could say was, “I didn’t.” You’re not going to get into it on the sidewalk and get into a prolonged defense of the situation. But there was a lot of misunderstanding because it happened so fast after I left. By the time they started negotiating, it was only three or four months after I left, which is very fast.

I was upset, first of all, that Mellon was being sold to anybody but particularly to Bank of New York. We knew them very well from having voluntarily tried to do a deal previously. We knew they hadn’t invested in their businesses, especially in their technology. We knew they had a different culture — they were more of a top-down organization and didn’t have the employee and customer orientations that we had built. I thought their lack of investment and their culture were problems.

So I wouldn’t have done the Bank of New York deal because I didn’t think it was as good a fit as it appeared to be. I would have done other deals if they had made sense. But I definitely would have resisted losing Mellon as the surviving company and therefore Pittsburgh as the surviving headquarters. Now, having said that, if the deal was so compelling that it was good for the shareholders and good for the other stakeholders when all the things were negotiated, I would not resist that kind of deal. With any deal, I would have tried to protect Pittsburgh because Mellon Bank was founded in Pittsburgh more than 100 years ago. It’s a major part of the community.

In terms of the community, if it’s a sale, as it really was with Bank of New York, you’re going to lose the headquarters clearly and you’re going to lose a lot more. If you’re positioning it as a merger of equals, which they did, Pittsburgh gets a little more. The only way we would have kept Pittsburgh as headquarters would have been if Mellon had been the acquiror — or if it had been truly a merger of equals.

One of the things that is very common in mergers or acquisitions is for the acquiror to give certain benefits to the acquiree – particularly to the community because it’s losing its headquarters. This helps get the approval of the selling directors and the shareholders, and it’s an important incentive. These benefits are to help get the deal approved and get you through the early years. And then they’re gone. Bank of New York did that. They set up a community fund of about $200 million to support charitable groups because Mellon had been a major community supporter for years. That $200 million from the acquiror’s point of view is just a cost of doing the deal. But that was very positive for the Pittsburgh community.

An Irish American’s Journey,

the Autobiography of Martin G. McGuinn, Jr.

Lyons Press ($29.95)

Bank of New York also said they’d try to keep as many people as possible in Pittsburgh. And they have, in terms of the numbers of people but not in the level of the people. To this day, BNY Mellon still has about 7,000 employees in Pittsburgh. So the numbers are there, but there are very few senior officers still in Pittsburgh. Some were around for the first two or three years and then either retired or went to New York. Some middle officers and junior officers remain in Pittsburgh.

Having the senior officers in the city is a big benefit of having the corporate headquarters because there’s a tradition of supporting the community, and the senior officers themselves are involved in the fabric of the community as leaders who support the community. It’s not just the corporate support; it’s the individual support. And so now, obviously Pittsburgh has lost some of the corporate support and the individual support from the senior officers.

Ultimately, with regard to Mellon’s decision to fire me, abandon our strategy and sell, the facts speak for themselves. In terms of the stock price, State Street and Northern Trust stayed independent and I think they’ve done a whole lot better. And certainly PNC had a different strategy, but they’ve also done much better. I think Mellon would have done much better on its own too. On Jan. 27, 2006 (the day before I was terminated), Mellon’s stock price was $36.11; 10 years later, at the end of the first quarter of 2016, Bank of New York Mellon’s stock price was $36.83. But now, BNY Mellon is doing much better and under CEO Todd Gibbons, the future is much brighter.

Being part of the Pittsburgh community has been an important part of my 40 years here, and I still have a residence here. Among my activities, I chaired the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, and the Senator John Heinz History Center. I have served as a Life Trustee for the Carnegie Museums and recently completed an eight-year term as Chairman of the Carnegie Museum of Art board. I was a board member of UPMC for 27 years and Vice Chair of the Pittsburgh Promise. I’ve supported the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, my alma mater Villanova University and many other colleges and schools. I have contributed substantially to the Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh and serve on the Bishop’s Advisory Board. With all of that, I’d like to think my commitment to Pittsburgh has been recognized as enduring.