The Blackest Day

“It isn’t the first step that concerns me, but both sides escalating to the fourth or fifth step and we don’t go to the sixth because there is no one around to do so.” JFK to EXCOMM

Previously in this series: DEFCON 3, Pt II

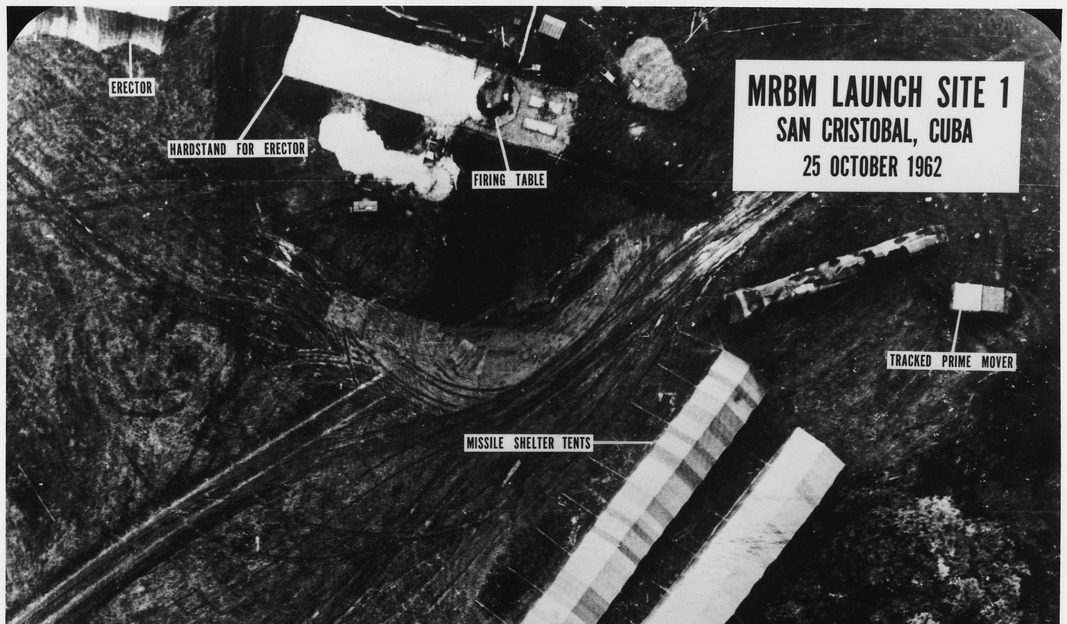

On October 25, 1962, the world was very close to nuclear war. The US had refused to accept the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba and was prepared to go to war over the issue. The Soviets had refused to remove the missiles and had accused the US of committing an act of war by quarantining Cuba. Soviet ships were heading to Cuba to break the blockade.

Then matters deteriorated.

Following the failure of the emergency session of the UN Security Council, the US put its military on DEFCON 2 status – the only time in American history this has happened. US B-52 bombers went on continuous airborne alert, 145 ICBMs stood on ready alert, and the entire American military was ordered to be ready to fight a nuclear war on six hours’ notice.

That same day the American quarantine was challenged by several Soviet vessels, but since those vessels were believed not to contain military equipment they were allowed through, thus at least delaying a final confrontation. Other Soviet vessels, however, were approaching the “quarantine.”

At 5:00 p.m. President Kennedy authorized the loading of nuclear weapons onto aircraft under the command of the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR, headed by General Lauris Norstad) – planes whose mission was to attack the USSR.

Friday, October 26

By October 26 President Kennedy himself was convinced that only a US invasion of Cuba had any chance of removing the missiles from the island. He issued an order to increase the frequency of the U-2 flights, but was persuaded by others at EXCOMM to give the Soviets a bit more time.

Saturday, October 27 – The Blackest Day

On the morning of October 27, a U-2 piloted by Air Force Major Rudolf Anderson departed its Florida base, flew to Cuba and positioned itself directly above missile sites near Guantanamo, taking hundreds of photos.

Seventy thousand feet below, two Soviet commanders were monitoring the U-2’s progress with increasing agitation. General Leonid Garbuz, Deputy Commander of the Soviet Forces in Cuba, and General Stepan Grechko, Deputy Commander of Air Defense, wanted to shoot the U-2 down, but technically only the overall Soviet commander in Cuba, General Issa Pliyev, could make such a decision.

One might have supposed that, given the crisis and the nuclear stakes involved, Moscow might have ordered its Cuban military not to cause trouble without Moscow’s approval, but this hadn’t happened.

In any event, General Pliyev couldn’t be located. “He was nowhere to be found,” Grechko would later say. Pliyev suffered from kidney problems, but it is also possible that Grechko’s remark was code for “Pliyev was too drunk to function,” a common problem with Russian generals then and now.

Now fully enraged and worried that the U-2 might escape, Grechko called Colonel Georgi Voronkov, Commanding Officer of the 11th Air and Defense Division, and, acting on his own authority, shouted, “Destroy Target Number 33!”

EXCOMM had considered the possibility that the Soviet’s might shoot down a U-2. Recognizing that this would represent a very serious escalation and would be a clear signal that the USSR intended to fight to keep its missiles in Cuba, the EXCOMM members decided as follows, according to Robert McNamara: “Before we sent the U-2 out, we agreed that, if it was shot down, we wouldn’t meet. We’d simply attack.”

Now the Soviets had shot down a U-2 and its pilot, Major Anderson, was dead. Why didn’t a nuclear war begin?

It so happened that when General Maxwell Taylor informed Kennedy about the downed U-2, Kennedy was meeting with EXCOMM – if that meeting hadn’t been going on, war might have broken out that afternoon. (The meeting had been convened to consider requesting that UN Secretary General U Thant ask the Soviets to pause work on the missiles.)

Outraged as the EXCOMM members were by the U-2 incident, the fact that they were gathered at the White House allowed discussions to happen, and those discussions considered the possibility that the incident had been as shocking to Moscow as it was to the US.

And this was, in fact, the case. Gen. Grechko had acted on his own authority and Khrushchev immediately ordered Gen. Pliyev not to shoot at unarmed U-2s.

But the blackest day wasn’t over. When Khrushchev announced that Soviet ships would ignore the American “quarantine,” he sent a flotilla of submarines to escort Russian freighters and to harass the US Navy ships enforcing the quarantine.

While Kennedy and EXCOMM were still reeling from the U-2 incident, the US Navy had located one of the Soviet subs – a B-59 Foxtrot-class sub. The Navy ships dropped “signaling” depth charges (about the size of a hand grenade) designed to let the sub commander know his ship had been located without actually harming the ship. These signaling charges sent this message: “We know where you are. Surface immediately or we will destroy you.”

This put the captain of the Soviet sub – Valentin Savitzky – in a terrible position. He had been out of radio contact and didn’t know if war had broken out or not. If he did nothing his ship would be sunk. But what the Americans didn’t know was that Savitzky’s sub was carrying nuclear-tipped torpedoes. If Captain Savitzky fired those torpedoes he would destroy the American surface ships, along with himself.

According to Soviet standing orders, nuclear torpedoes could only be launched if both the captain and sub’s political officer agreed. Under intense pressure, Captain Savitsky sought out the political officer, Ivan Semyonovich Maslennikov. The men discussed their plight and agreed that the torpedoes should be launched – they would die as heroes. And that certainly would have launched a nuclear war.

But it didn’t. Why not? We’ll look at that interesting issue next week.

Next up: Ukraine through the Lens of Cuba, Part 4