Monty Murty casts a tiny fly — a Parachute Adams — from his bamboo rod to the surface of a stream in Linn Run State Park, instantly tempting a wild brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) to bite.

He brings the feisty fish to hand, pausing to admire its vibrant, speckled skin before removing the barbless hook from its mouth and returning it to the water unharmed.

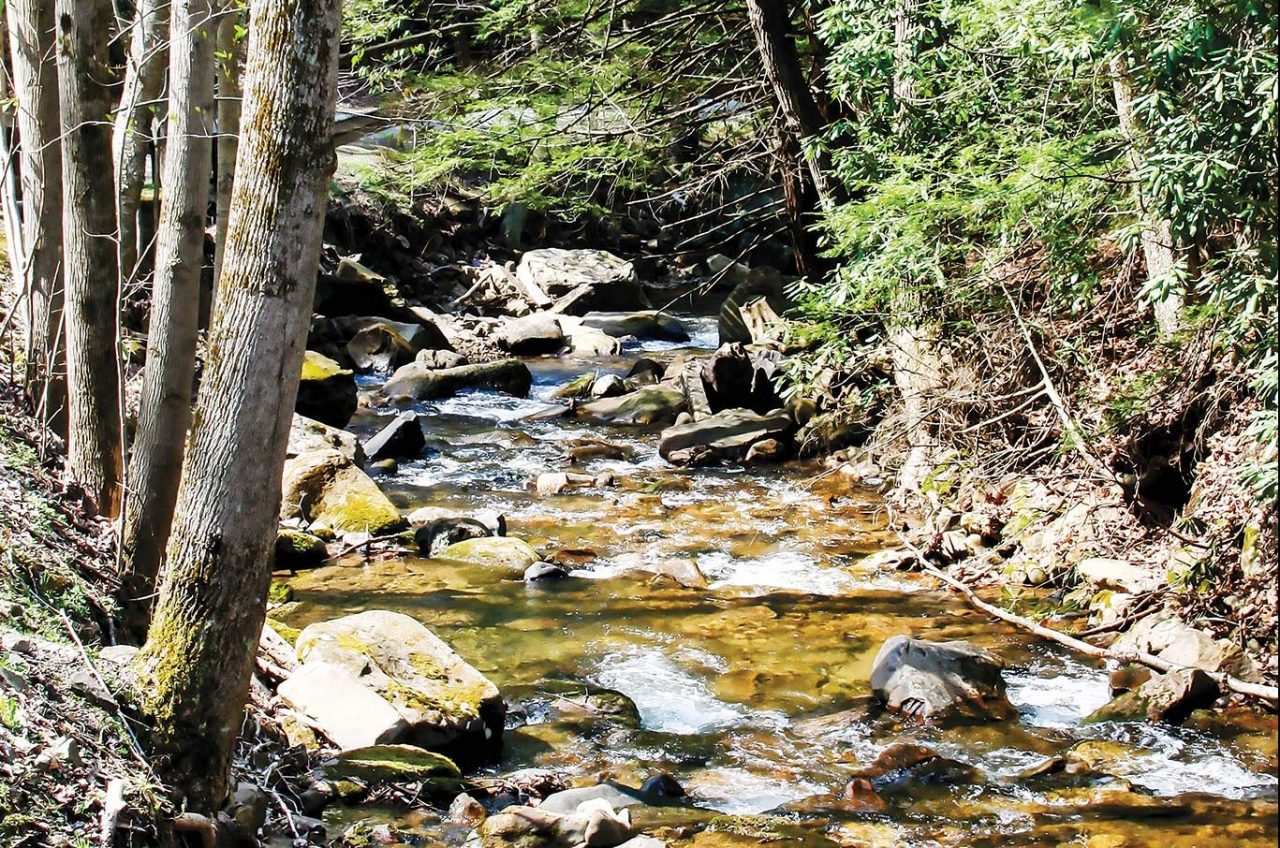

Still spry at 76, Murty continues up the small mountain stream, stealthily targeting pockets and pools around boulders and logs for the little native gems that inhabit this and other parts of the Linn Run watershed in Westmoreland County. Although hatchery trout are routinely stocked just across the road in Linn Run, for Murty, a past president of the Forbes Trail Chapter of Trout Unlimited, targeting them is the piscine version of miniature golf, and he is drawn instead to stream-born brookies — Pennsylvania’s state fish — as both an angler and a conservationist.

“Fly fishing is as much about protecting wild, native trout as it is catching them,” he says. “They are a precious natural resource.”

Murty wants to see more of them in the Laurel Highlands, where they no doubt thrived before acidic rainfall and climate change began to take a toll on their numbers. To that end, he and other senior members of Forbes Trail Trout Unlimited have embarked on an ambitious plan to assess the watershed and determine where habitat can be improved enough to help wild brook trout proliferate.

The research — much of it performed by trained volunteers — began last year to assess the quality of habitat, aquatic insect life, forest canopy, and the health of wild brookies. Data collection and analysis continued this year with generous funding and in-kind support from a slew of partners, including The Foundation for Pennsylvania Watersheds, Powdermill Nature Reserve, Saint Vincent College, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, and various state agencies.

releasing it back to the water unharmed.

“We’re looking at the watershed from the first raindrop at the top of the mountain to the end of Linn Run — about six miles,” says Forbes Trail Trout Unlimited president Larry Myers, 71. “At the end of two years, we’ll have the first-ever coldwater conservation plan for Linn Run and its tribs. We’ll know where remediation is needed and, if our partners agree, seek the funding to get it done.”

A draft plan is expected to be finished sometime this summer.

While the entire Linn Run watershed is designated High Quality–Cold Water Fishes, of pivotal interest is how much the pH of the streams has improved since Penn State University research 40 years ago revealed that acidic rainfall was leaching limestone from the upper reaches of the mountain and thus diminishing geologic buffering capacity.

The hope is that a decline in coal-fired power plant emissions since passage of the Clean Air Act Amendment of 1990 has helped to ease impacts, Myers says, noting that there are encouraging signs. The results of a 2021 study of macroinvertebrates in more than a dozen streams, including Linn Run, indicate good water quality.

Sampling in June and November confirmed a rich presence of mayflies (Ephemeroptera), stoneflies (Plecoptera), and caddisflies (Trichoptera) — the EPT orders — says Powdermill entomologist Andrea Kautz, who led volunteers in the collection effort and then analyzed the insects in her lab to determine not just their families but their genera. “We found lots of great bugs — the kind trout like to eat.”

These pollution-sensitive orders generate hatches prized by anglers, too, and their abundance and diversity reflect habitat health, Kautz says. “Mayflies are especially vulnerable to acidic waters and can be missing. But we found plenty of mayflies.”

Linn Run State Park once a month. Water chemistry is a pivotal factor in native trout survival and productivity.

Coincidental to the Trout Unlimited project, Grove Run and another, unnamed, Linn Run tributary were added in 2021 to the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission’s list of Class A wild trout waters, which means that the bio-density and year-class diversity of naturally reproducing trout meet the agency’s highest standards.

Coaxing other streams — currently ranked classes C and D — to excellence will be a significant challenge, says fish and boat commission biologist Gary Smith. “I think Trout Unlimited has something to work with, so I won’t say it’s not possible. But acidic water is a problem and it’s going to take a lot of money to address.”

Trout Unlimited has evidence that it can be done, with the success of a limestone dosing project it began experimentally in 2007 on Rock Run, Linn Run’s largest tributary. So far, a total of 575 tons of sterilized, granulated limestone — at $58 a ton — have been shoveled into the run at its headwaters on the Laurel Mountain summit to sweeten water in the lower reaches. Brookies placed in the stream a decade ago to see if they would survive have evolved into a self-sustaining colony near the mouth of Rock Run.

Elsewhere in the watershed, other more emergent problems are being addressed, including hemlock woolly adelgid, a non-native, sap-sucking insect threatening conifers on some streams, Myers says. “Trout need cold water to survive, especially in summer, so losing trees that provide shade and cover could be devastating to a fishery.”

Also worrisome are gill lice, a parasitic crustacean common in trout streams across the state and now documented in Linn Run tributaries. Although the extent of their impact on longevity and reproductive success isn’t fully known, studies suggest that trout populations decrease where gill lice occur, Kautz says.

insects are living there. Recent sampling of more than a dozen streams in the Linn

Run watershed revealed a rich presence of mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies,

which are indicators of water quality

There is much work ahead for TU and its partners, but the half-dozen Forbes Trail members who are shepherding the effort have eagerly taken it on in homage to the fly-angling tradition.

“The highest form of trout fishing is providing for future generations of anglers,” says Murty, who sees the project as the legacy of those who cherish the resource.

“We love to catch fish,” says Forbes Trail vice-president Denny Hess, 67, who leads the Rock Run limestone remediation project. “And this is our way of giving back.”