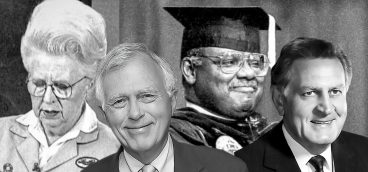

Gailliot, Kuller, Dudreck, Charny, Calaboyias, Barricella, Harris

Henry Gailliot, 80

A Central Catholic valedictorian, Gailliot earned a BS and MS in industrial management, followed by a PhD in economics from Carnegie Mellon. He spent his career at Federated Investors, becoming the company’s senior economist and a member of the Executive Committee.. He served on the boards of the Children’s Museum and the Carnegie Museum of Art, where he co-founded the Collections Committee. He was a Life Trustee of Carnegie Mellon and a founder of the National Institute for Newman Studies. Aside from the opera and symphony, Gailliot loved spending summers on Nantucket with his family or sharing adventures with them in Europe, Africa, and Asia.

Dr. Lewis Kuller, 88

He chaired Pitt’s Department of Epidemiology from 1972 until 2002, overseeing research in aging, women’s health, diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular disease, including the landmark Women’s Health Initiative and the Cardiovascular Health Study, which made significant contributions to understanding the progression of heart disease. He received numerous awards, including the American Public Health Association’s John Snow Award, the Chancellor’s Distinguished Research Award, and the American Heart Association’s Peter J. Safar Pulse of Pittsburgh Award.

Albert Dudreck, 91

He was the ad man behind many well-known print, radio and TV ads. He created the Kings Family Restaurants billboards with owner Hartley King holding bowls of ice cream. He hired Kathy Svilar as the “Shop ’n Save lady,” a job she kept for 25 years, and made the Seven Springs Mountain Resort logo. Dudreck was co-founder of Dudreck, DePaul, Ficco & Morgan Advertising, better known as DDF&M, and ran the firm for 30 years.

Dr. Joe Charny, 95

A Tree of Life synagogue shooting survivor, Charny said in his autobiography, “We are born, we laugh and we die.” It was his version of the bleaker sentiment, “We are born, we suffer and we die,” and reflected the optimism for which he was known. The former Tree of Life board president hoped the synagogue where he led services for 20 years would reopen. A psychiatrist who taught at Pitt, he practiced privately full time as an advocate of psychoanalysis and served as director of clinical services at Woodville State Hospital.

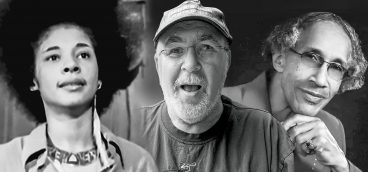

Peter Calaboyias, 82

His sculptures, installations and public art projects dotted the country but his most recognized piece was “Tribute,” a bronze sculpture he designed to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Olympic Games. The work, commissioned for the City of Atlanta, includes bits of nails and other shrapnel from a pipe bomb that tore through Atlanta’s Centennial Olympic Park in the summer of 1996. Calaboyias’ “Silver Grid Wall,” a 78-foot-long aluminum-paneled screen, greeted visitors at Pittsburgh International Airport for nearly 20 years.

Judith Barricella, 75

Contracting polio at 4, she used a wheelchair her whole life, so it was with some experience that Barricella became Allegheny County’s first American with Disabilities Act coordinator. She was at the White House in 1990 for the signing of the landmark legislation aimed at improving equality for those with disabilities. Early in her career, she started a speech therapy program at the Association for Retarded Citizens (now Achieva), and in 1980, she was the founding director of the Center for Independent Living, where she served for 10 years.

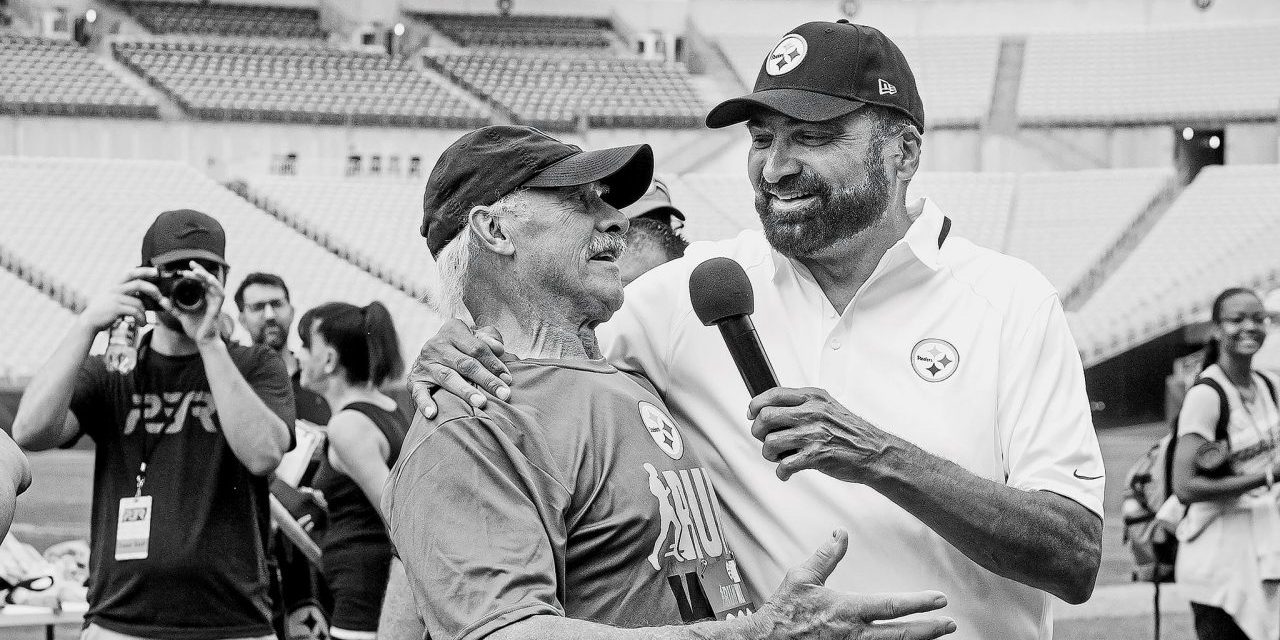

Franco Harris, 72

Harris was a Hall of Fame Pittsburgh Steeler who was the hero of pro football’s greatest play and an exemplary Pittsburgh citizen who set the standard among local sports heroes for using his celebrity status to improve his city. A biracial New Jersey native — his father was a black U.S. soldier who met his mother, a native Italian, during World War II — Franco was a standout running back at Penn State who was the Steelers’ first-round draft pick in 1972. His arrival changed the Steelers’ trajectory from long-time losers to the greatest NFL dynasty. He was named “Offensive Rookie of the Year” the same year that he entered NFL and U.S. cultural history with a play that electrified anyone who saw it. Harris rescued an apparently failed, last-minute desperation play — catching a ricocheted ball just before it hit the ground and running it in for the winning playoff touchdown — “The Immaculate Reception.” He was one of the most powerful, dominant running backs in NFL history; when he retired, he was third all-time in yards — trailing Jim Brown and Walter Payton and ahead of O.J. Simpson. But it is broadly acknowledged that his true greatness was in his tireless and selfless efforts to help others — from a sick youngster in a hospital to Pittsburgh’s most ambitious civic campaigns (The Pittsburgh Promise and many others). Always a warm, gracious and friendly presence, Franco Harris was that rare example of the tremendous power for good that a celebrity can have in making the world a better place. As longtime Steelers public relations director Joe Gordon said, “As great as he was on the field, no one could ever match who he was off the field.”