Date With Destiny

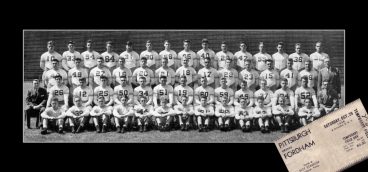

The Washington & Jefferson football team had its work cut out for it on Jan. 2, 1922.

The Presidents had gone unbeaten that year, taking on powerhouses such as Pittsburgh, West Virginia and Syracuse. They were invited to play the University of Detroit in a postseason matchup, and after winning that game, touted as a “mini-Rose Bowl,” they were invited to the real thing, to take on the University of California Golden Bears. It would be a daunting task.

The Wonder Team of California hadn’t lost a game since 1919, and in the previous year’s Rose Bowl, had demolished Ohio State, 28-0. That team had become one of the great powers of the Midwest, thanks to All-American Chic Harley, who inspired so many fans that a new stadium was under construction on the banks of the Olentangy River in central Ohio. Who knew anything of Washington & Jefferson? Certainly not anyone west of the Mississippi. Jack James of the San Francisco Examiner said the only knowledge people in California had of Washington and Jefferson “is confined to one simple, salient fact: They’re both dead.”

In fact, James reported, California asked for the bulk of the gate receipts (at least one-third, or $48,000) with the knowledge that they were going to be the main draw. What kind of fight could Washington & Jefferson put up, especially after a weeklong train trip to California?

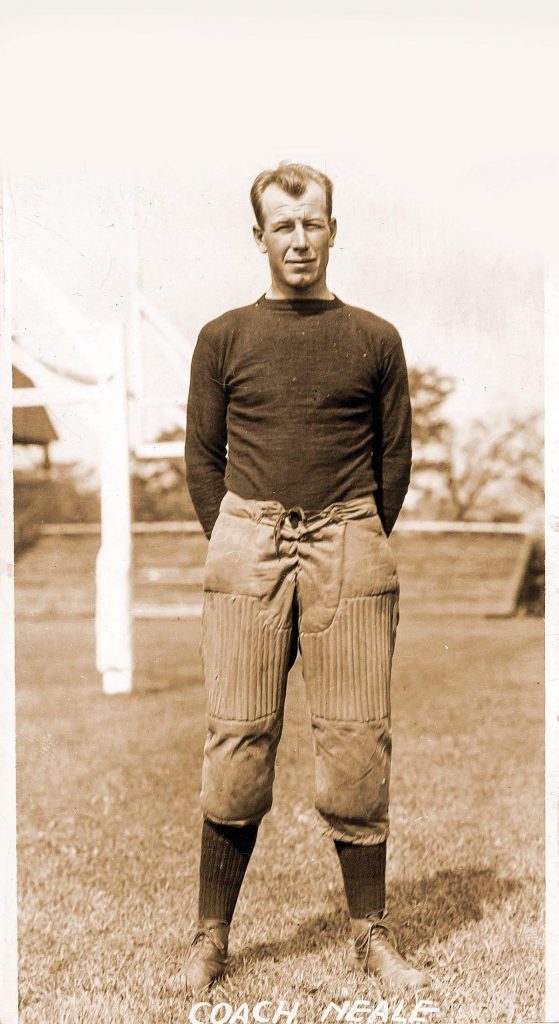

“The California papers acted as though our presence in Pasadena was a deliberate insult,” W&J coach Earl “Greasy” Neale recalled in a 1951 Collier’s magazine article. The morning of the game, one fan told Neale that W&J would lose by 14 points. “Listen,” Neale said. “California couldn’t score 14 points against this team if they started now and played until it got dark.”

He turned out to be right.

Given that every fall weekend is wall-to-wall college football, an enormous (and enormously lucrative) spectacle, it’s hard to believe the humble origins from whence it came.

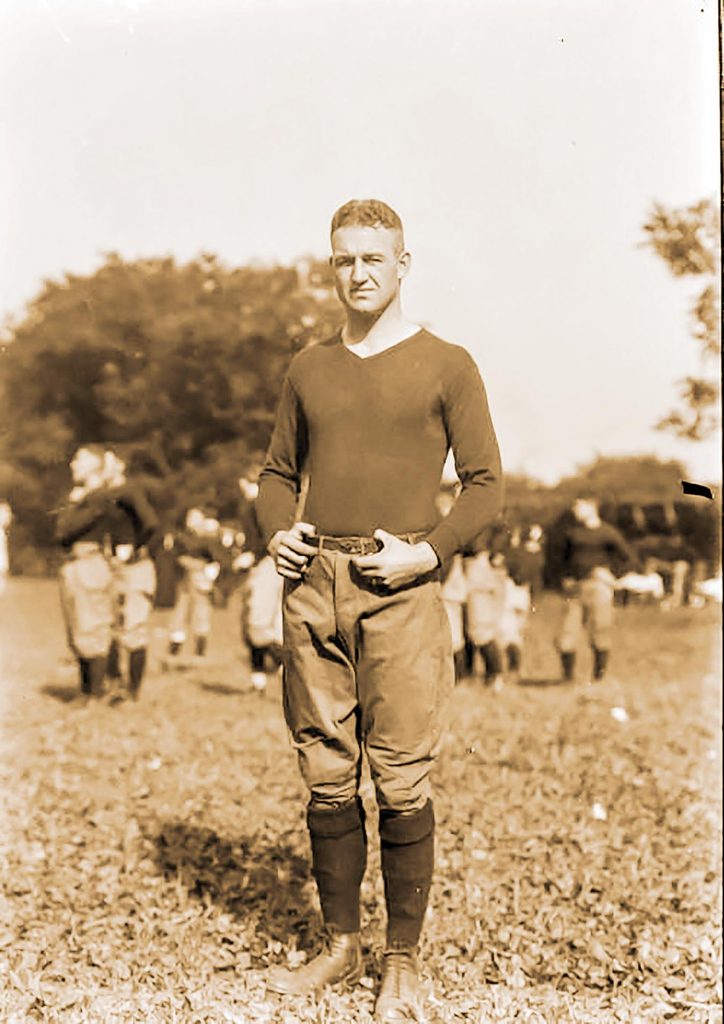

A century ago, the game of football — on every level — looked vastly different from how it’s played today. Players wore little padding, no face masks and leather helmets, and it was not only common for players to play offense and defense, it was expected. In response to college football players regularly getting seriously injured or even killed, President Theodore Roosevelt had convened administrators from the largest universities in the country to standardize rules for safety’s sake. Thus was born the NCAA, which promptly legalized the forward pass. Still, in 1921, the running game dominated.

Conferences didn’t have the stranglehold on the game that they do today, and many teams were independent, scheduling games with whatever opponents they could. There were no bowl games other than the Rose Bowl, which started out as a secondary focus for the Tournament of Roses Parade, first held by the Valley Hunt Club in 1890 in Pasadena. Photos of roses in bloom in the dead of winter so mesmerized eastern audiences that it became an annual tradition. The secondary activities included tug-of-war, track events and a polo game.

In 1902, parade organizers invited the University of Michigan to play Stanford’s football team. The Maize and Blue, featuring Fielding Yost’s famed “point-a-minute” offense, beat Stanford so badly, 49-0, that the game was called with eight minutes remaining, putting an end to football at the Tournament of Roses — at least for 14 years. The tournament decided to hold chariot races until 1916, when the game was revived, with Washington beating Brown, and has been played annually since.

In sum, it was the perfect landscape for a team like Washington & Jefferson to be a prominent player. The Presidents are now Division III, but a century ago, the nascent NCAA made no distinctions for divisions for schools. The team had some success in the 1910s, as coach Bob Folwell amassed a 35-8-3 record in four years as coach, including an unbeaten record in 1913, but their fortunes had declined following his departure for the University of Pennsylvania.

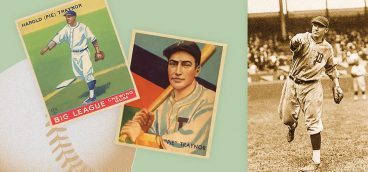

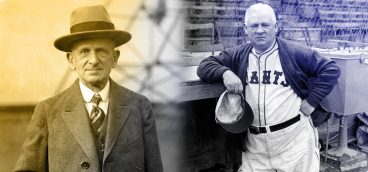

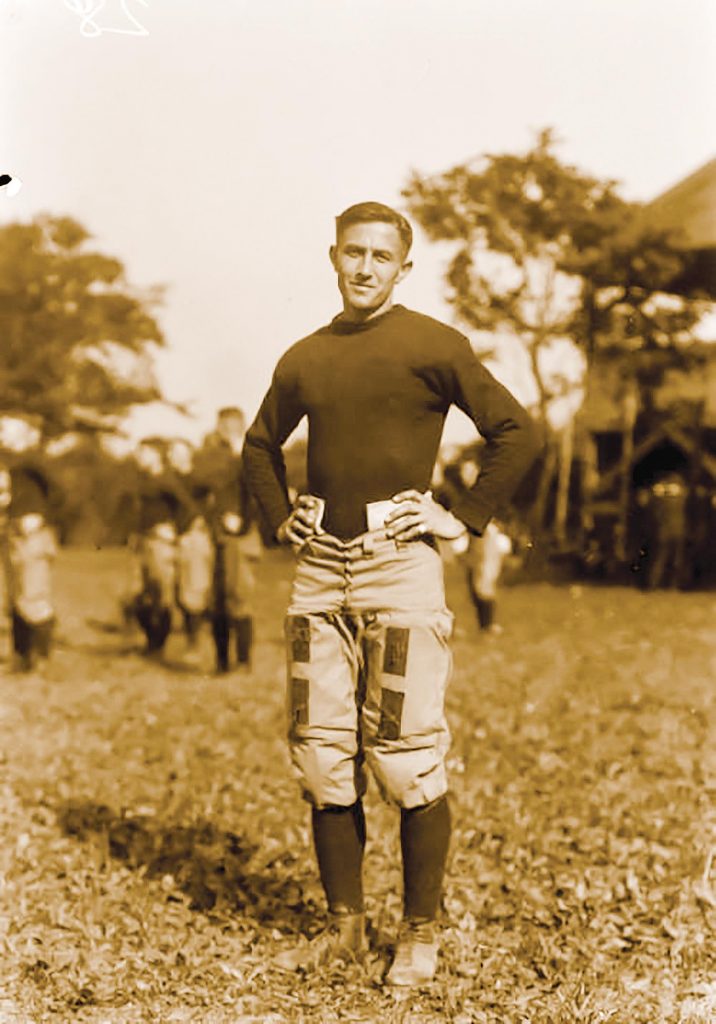

That changed on March 6, 1921, when the college hired Earl “Greasy” Neale as head coach. Neale had started coaching while he played football for his high school in Parkersburg, W.Va. Baseball was his first love — he played for the Cincinnati Reds, and coached as his off-season job — but he would end up having more success in football than baseball. He’d spent time on the sidelines at his alma mater of West Virginia Wesleyan and Marietta College before being hired at Washington & Jefferson.

W&J originally wanted Gil Dobie, a titan of college football coaching at that time who’s been mostly lost to history since, but Dobie turned the job down.

“The entire football season at Washington & Jefferson hinges upon defeating Pop Warner at Pitt and that’s too much of a task,” Dobie said.

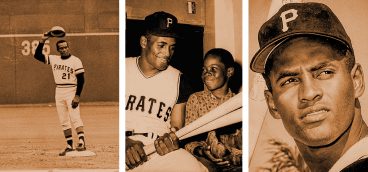

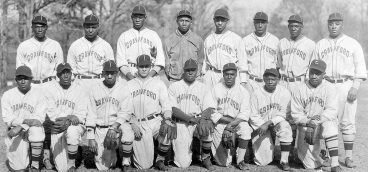

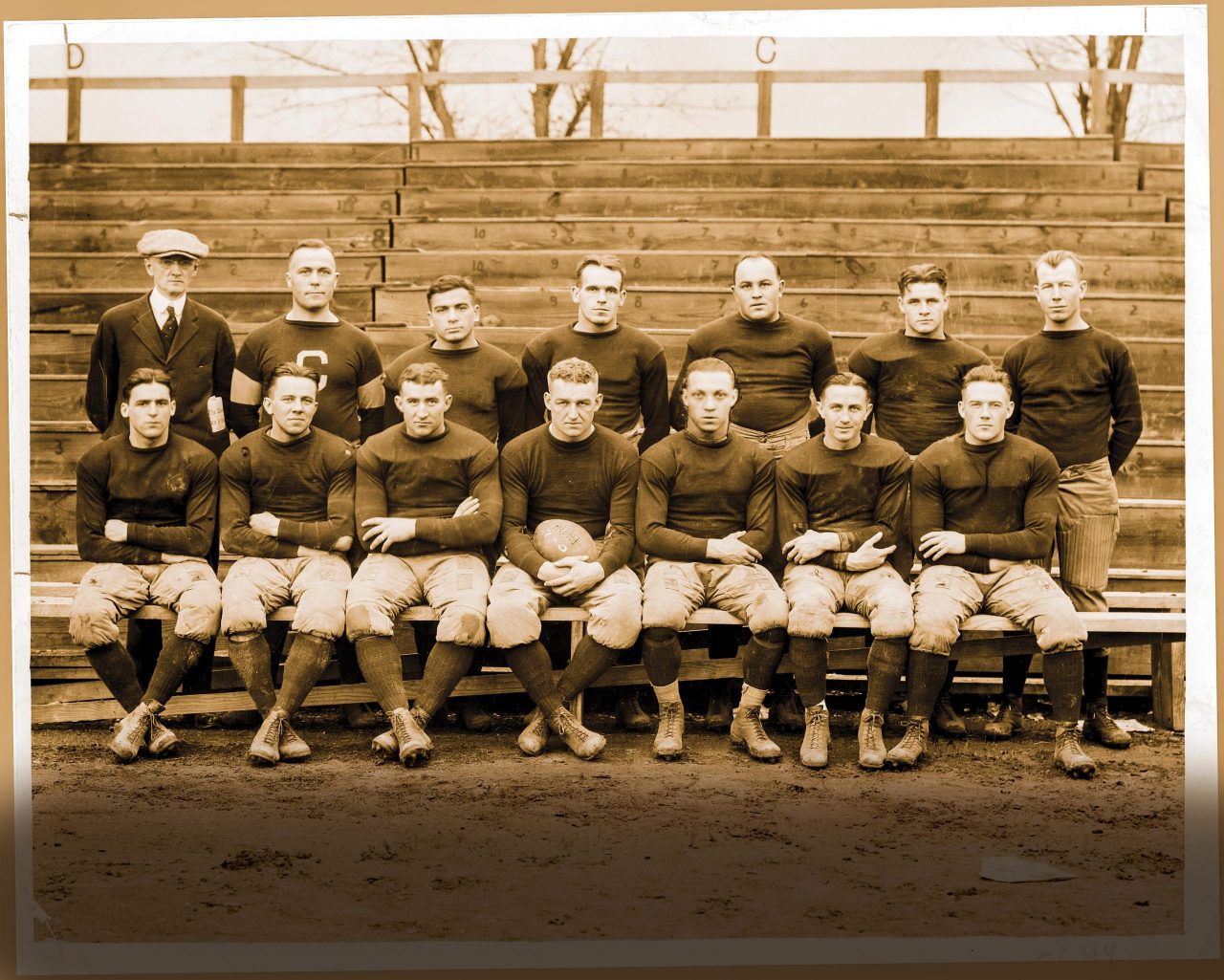

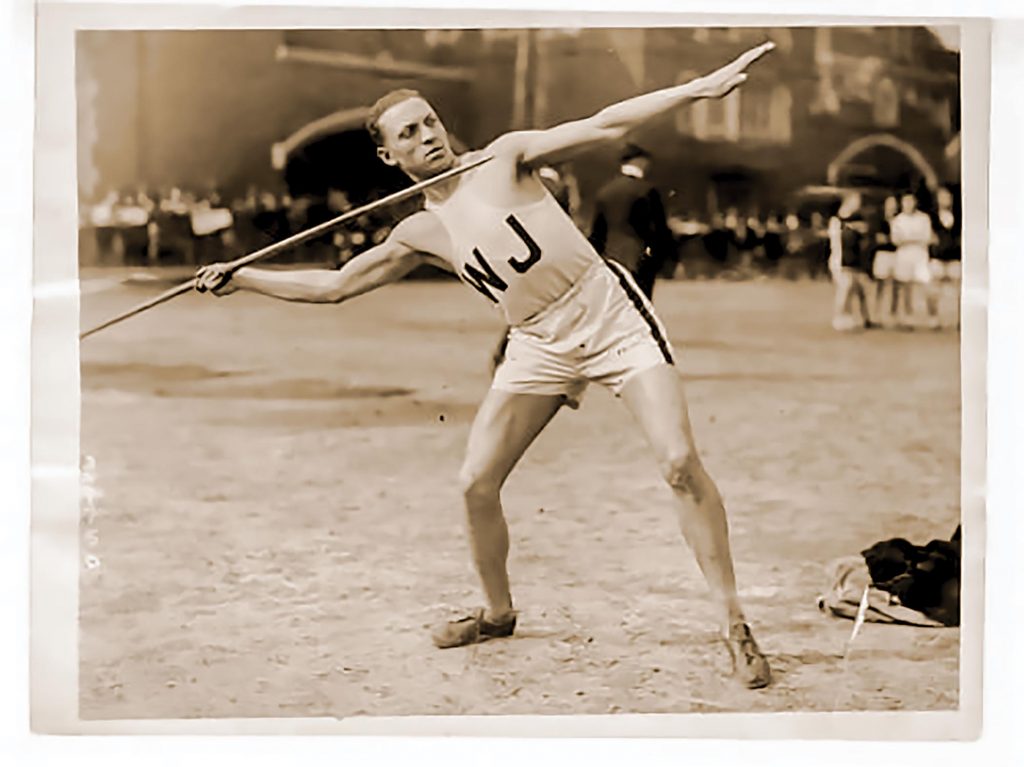

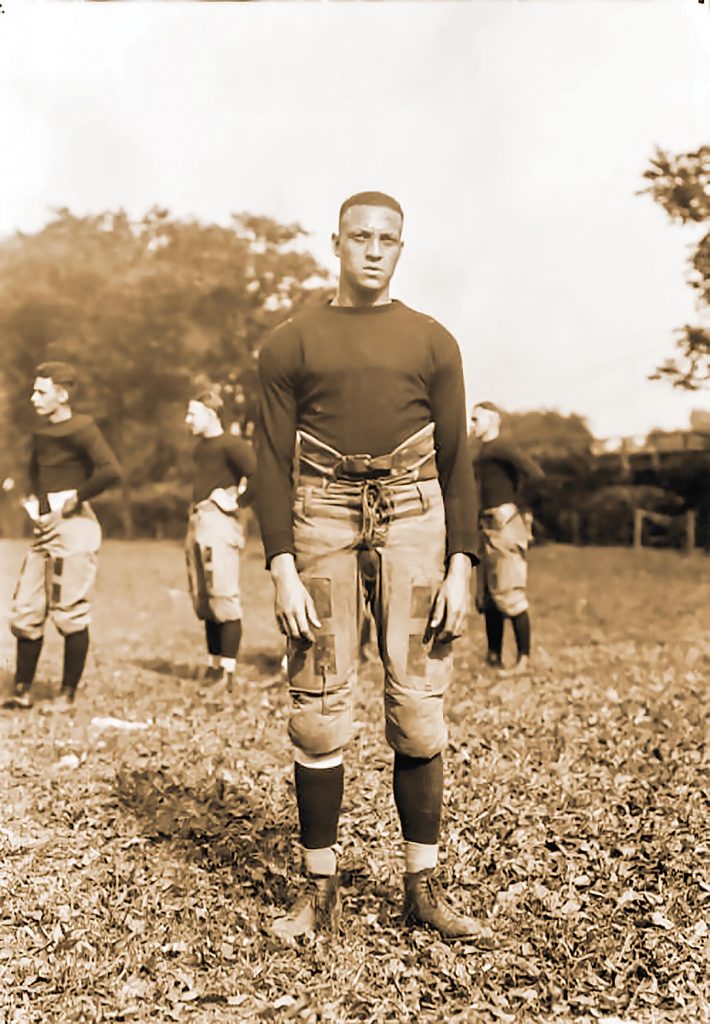

Not only did Neale think he was equal to the task, he said if he couldn’t beat Pitt, then he’d coach for free. He knew he had the horses to do it. Team captain Russ Stein was an All-American. At halfback was Charles “Pruner” West. The son of a local store owner, West was an honorable mention All-American and a star on the track team. He was also a rarity: An African-American student at a private college.

Neale was also able to get his hooks into freshman Herb Kopf, whose brother Larry was Neale’s roommate with the Reds. “Herb wanted to go to Princeton,” Neale recalled. “Just before he left to take the entrance exams, I shouted at him, ‘I hope you flunk.’ He didn’t even take the exams.”

The Presidents hosted four straight home games to open the season, pitching a shutout in each of them. (Neale gave no quarter to his alma mater, shellacking West Virginia Wesleyan 54-0.) The Presidents went on the road to beat Lehigh and Syracuse (with West scoring on a 95-yard kickoff return). Neale and several other staff members skipped the team’s game against Westminster — a 49-14 win — to scout Pitt. The following week was the showdown at Forbes Field. Wayne Brenkert threw a 19-yard touchdown pass to Kopf, the only scoring in the Presidents’ first win against Pitt since 1914, prompting a day of celebration in Little Washington. W&J closed out the season with a shutout of West Virginia, and then were invited to play a game in December against Detroit at what was then called Navin Field, but would later be known as Tiger Stadium. Cornell, Lafayette and Penn State were, like Washington & Jefferson, undefeated, but it was the Presidents who got the invitation to the Rose Bowl.

Of course, they accepted. But how would they get there?

Just as college football of the 1920s bears little resemblance to the game played today, traveling at that time was much more difficult as well. In 1919, a convoy of military vehicles — including a young West Point graduate named Dwight D. Eisenhower — left Washington, D.C. to travel to San Francisco on the new Lincoln Highway. They averaged 58 miles a day. There was no commercial air travel to speak of. That meant traveling by train to southern California.

The team left from Pittsburgh on Christmas Eve. Just 20 people made the trip. It was literally all who could afford to go; Athletic Director “Mother” Murphy mortgaged his house for travel expenses. Neale had also brought gallons of water with him from Washington. The lackluster performance of eastern teams out west was attributed in part to dysentery, and he would take no chances.

Two days later, the team got out for a practice at the Kansas City Athletic Club. They were forced to leave Lee Spiller in Kansas City. He had pneumonia. The train ride itself was a learning experience for the Presidents, as a headline from the Washington Reporter on Dec. 28, 1921, noted, “Flat Country a surprise to W&J gridders.” The paper also detailed the Presidents’ trip to the Grand Canyon on Dec. 29. (Neale didn’t allow the team to take burro rides down to the base of the canyon, fearing the toll the altitude might take on his team.) Finally, the team arrived in southern California on New Year’s Eve.

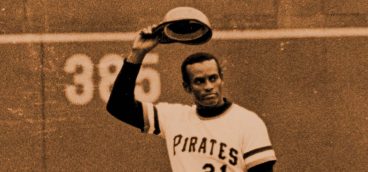

More than 50,000 people were on hand for the football game at Tournament Park. (Plans were being made for a new stadium, and construction would begin in February on a facility modeled on the Yale Bowl, then the largest stadium in the country.) Just by taking the field, West and Kopf were part of history. Kopf was the first freshman to play in a Rose Bowl, and West, who had assumed quarterback duties as the season went on, was the first black quarterback, and just the second black player in the game’s history.

Back home, fans were enrapt, following along as best they could. It had been little more than a year before that KDKA in Pittsburgh had started broadcasting news, sharing returns from the presidential election, where Warren Harding, the first popularly elected senator from Ohio thanks to the 17th Amendment, had defeated Ohio Gov. James Cox, whose running mate would go on to great things in his own political career: Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Prior to the advent of radio, people would gather outside the local newspaper office for scoring updates — and some newspapers went as far as to put up a simulated field to re-enact game action. Fans who couldn’t make it to Pasadena, or couldn’t get to a radio, were invited to the Globe Theater in downtown Washington to watch the game be “reproduced,” according to advertisements at the time. A model gridiron, replete with hundreds of small lights, would be able to convey basic action. “Lights skillfully manipulated all around the board show the audience not only the position of the ball on the gridiron, but which side has possession and the member of the team making the play, be it a line plunge, end run, forward pass or punt,” wrote the Washington Reporter.

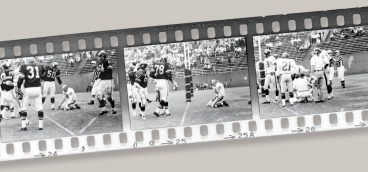

W&J got the ball to start the game, and moved down to the Cal 35-yard line. The Presidents lined up in punt formation, but Brenkert ran the ball for a touchdown. But the score was called back. Stein was offside. On the next play, Cal intercepted, but could only gain two yards before turning the ball over on downs. It had rained on New Year’s Day, but it wasn’t field conditions that stymied Cal. The Washington & Jefferson defense swarmed them, and the game became a punters’ duel.

W&J had two more scoring chances, as Stein tried two different field goals, one going wide and the other blocked. The game ended in a scoreless tie. Cal was held to two first downs — a mark that will probably never be equaled, nevermind surpassed at a Rose Bowl. Another historic mark? W&J played the game with no substitutions. Only 11 players saw the field for the Presidents.

Even the San Francisco journalist Jack James had to admit this Washington & Jefferson was very much alive, saying, “A truly remarkable eleven from a little college in western Pennsylvania came across the continent and accomplished a feat that numerous institutions of ten times the enrollment and treble the athletic reputation have found impossible.”

Following the Rose Bowl, W&J won its first six games in 1922. But the season ended with three losses and a tie, and Neale was forced out, going to the University of Virginia, where he also served as baseball coach. He called his time in Charlottesville “the happiest years of my coaching career.” He then went to Yale and joined the pro ranks, serving as coach for the Philadelphia Eagles. He’s an inductee of both the college and professional football halls of fame.

“Pruner” West was named to the 1924 Olympic team, but didn’t participate. He ended up going to medical school at Howard University and was a doctor in the Washington, D.C. area until his death in 1979. In 2017, he was inducted into the Rose Bowl Hall of Fame.

Herb Kopf coached in the college and pro ranks, and was one of the last surviving members of the team when he died in 1996. Russ Stein played professional football in the nascent NFL. A native of Niles, Ohio, he ended up in the Cleveland area, and for years after, his teammates busted his chops about being offside. “Aww, c’mon, fellas,” he said at a reunion in 1961. “Let’s let bygones be bygones.”

Neale’s successor at W&J was even more highly touted, a well-traveled football coach with two national championships under his belt: John Heisman. But Heisman, too, was forced out, and W&J’s internal issues — combined with the rise of other midwestern powers — led them into the ranks of also-rans.

But as the smallest school ever to play at “the granddaddy of them all,” W&J will always be a part of Rose Bowl history. And with all the conference tie-ins and the bowl’s participation in the College Football Playoff, that’s a record that will likely never be eclipsed.