The Studied Neglect of the Hill District

The dreariest part of a recent trip to Pittsburgh was not the memorial service I attended, but revisiting the Hill District.

I’ve always felt a connection to the place, first referred to as “Jew’s Hill” during my grandparents time. Then with the great migration of blacks coming north after the Civil War, the named changed to “Up South” and then “Little Harlem.”

From the 1880s to the 1930s, Jewish life was centered in the Hill District which at its height featured some 25 synagogues, several community centers, hundreds of businesses and theaters featuring Yiddish productions. My non-observant grandfather used to tell stories of trying to provide for a family on Reed street, drowning in the depth of the Depression. On a daily basis he’d run into an observant shopkeeper named Wecht, wanting to discuss Torah and incessantly “kvelling“ about his gifted son, Cyril. Eventually my grandparents and the Jews moved to Squirrel Hill.

Blacks came to populate the hill, first as a result of the Jim Crow repression after the Civil War. In the words of scholar Emmett J. Scott, “They left as though they were fleeing some curse. They were willing to make almost any sacrifice to obtain a railroad ticket.“ The Great Migration from the 1910s until 1970 came as a result of unmet promises of the Civil War. In the 1880’s Jim Crow laws retained a caste system that would not ostensibly end until the passage of the Civil Rights laws in the 1960s.

The social realities were such that young men were scared to be near white women, given the distinct possibility that they would end up hanging from an oak tree. Also economic reality was such that black sharecroppers were often left with nothing at the end of a growing season as a result of annual accountings rigged by landowners. And the ever-declining prices of cotton made for a losing situation. As a result, some six million blacks migrated to northern urban centers. Contrast this to America’s second biggest migration west involving 300,000 people during the Gold Rush.

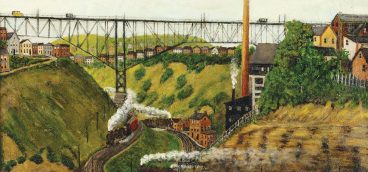

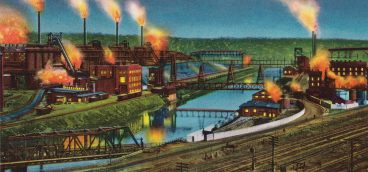

A dedicated public relations campaign promised a secure future in the north, with mail order catalogues sent south in the early 1900s touting unmatched opportunities. The Pennsylvania Railroad, meat-packing houses and steelmakers dispatched recruiters. Mindful of the violent propensities of southern landowners who depended on black workers, recruiters assumed the guise of door-to-door insurance salesmen. And with immigration to the U.S. plunging by more than 90 percent from 1914 to 1918, industries needed a new source of labor. In the 1880s, the population of the Hill District was 10,000, exceeding 20,000 in 1907, 25,000 in 1910 and 100,000 by 1960.

Promises notwithstanding, good jobs in the mills and mines were generally not available to blacks. Instead, they held menial jobs; janitors, laundresses and maids. If they were lucky they worked as shop clerks, railroad porters, or low-level laborers.

My lonely mid-day drive through the Hill’s various avenues evidenced nothing of the vibrant community, which between the 1930s and 1950s was called the “crossroad of the world” when it came to sports, music, arts and culture. I didn’t come across one person.

Starting from the US Steel Building I drove up Centre Avenue, passing on my left a massive earthen pit that was once the Civic Arena. The Arena was completed in 1961; a key component of the Pittsburgh “Renaissance.” While it was a boon to the steel industry and big labor, it took a massive bite out of homes and businesses, eviscerating the Lower Hill District. This was all the brainchild of a host of white-shoe corporate types who were eventually called “The Allegheny Conference.” Munching on crudites at the Duquesne Club, they worshipped the deity of “urban renewal.” What made this exercise viable was the endorsement of Democrat kingmaker, Mayor and then Governor, David L. Lawrence. He supplied the muscle to secure passage of the Urban Renewal Act which created authorities that could condemn property through the power of eminent domain and issue tax-exempt bonds paying for projects to combat “blight.” Needless to say, one man’s blight was another’s community.

The URA later admitted that over 1,000 units of dwellings were lost. Some 8,000 people and four hundred businesses were displaced.

The promise of upscale living close to downtown Pittsburgh came with 24-story luxury apartment Washington Plaza, designed by no less an architect than I. M Pei. Across the street still remains Saint Benedict The Moor Parrish established in 1889 by Holy Ghost University (now Duquesne) specifically in recognition of the spiritual needs of black Catholics. In 1968 an immense statue of a moor with outstretched arms was installed, looking down from its lofty perch on the entire City below. The question remains as to whether it is a welcoming gesture or something foreboding. Maybe it’s about a last stand against the Renaissance which was killing its community.

Driving up another block to Dinwiddie Street, I passed the remains of a strip shopping center originally designed to anchor a full service grocery store, that proved unsustainable. Across the street, I came across a ragged multi-story building, coming apart at its seams, standing upright thanks only to mausoleum-like scaffolding. Passers-by wouldn’t know that this was the renowned “Roosevelt Theatre: The Showplace of the Hill” which opened in 1929 complete with a lobby oil painting of Teddy Roosevelt, vaudeville shows and “photoplays.”

Onward to the intersection of Centre and Kirkpatrick, once the bustling “Times Square” of the Hill. This is where I worked in the summer of 1969 in a two-story walk-up that was the district office of State Representative K. Leroy Irvis. Only one year earlier, five days of rioting over the Martin Luther King assassination resulted in 505 fires, 100 businesses being vandalized and 1.000 arrests. Nonetheless, during my internship, activity remained in the way of a gas station, several stores and community service storefronts. It seemed normal enough to me, but I did not realize that Irvis had a neighborhood guy serendipitously appear to accompany me on my neighborhood outings. It only dawned on me decades later that this naïve 17-year-old was being provided protection. Now the district office and much everything else at the three-way intersection is either boarded up or demolished.

Turning left on Kirkpatrick, I drove up to Wylie Avenue. Again, there was no evidence of life there either. Proceeding left down Wylie avenue I saw what was symptomatic of the remains of the Middle and Upper Hill. It was as if a neutron bomb went off, leveling nine of every 10 structures, replacing them with grass.

Next up was a three-story dilapidated building undistinguished except for a historic marker describing it as the “Crawford Grill.” Another closed bar? Hardly. The Crawford Grill symbolized a once-thriving black renaissance preserved on film by Teenie Harris, the son of parents who operated a boarding house for those coming north around World War I. He was the younger brother of numbers king Woogie Harris, and a former numbers runner. Known as “One shot,” given the need to conserve film and flashbulbs, Teenie depicted life in all aspects on the Hill particularly during the two decades from World War II on. The breadth of those activities were every bit as rich as those engaged in by whites. There were portraits of patriotic supporters conducting blood drives and war bond efforts. There were pictures of children with Santa, horseshoe contests, swimming excursions, YMCA events, mariachi bands, equestrians complete with jodhpurs, gloves and riding crop, hunting clubs displaying deer that were just bagged, and a host of elite fraternal groups, male and female, one of which was oddly enough named “The Frogs.” There were portraits of funeral homes, their owners and their proudly displayed cavalcade of vehicles, not to mention every conceivable keep sake remembrances of births, weddings and deaths. Politicians, be they Presidential aspirants or local candidates courting the black vote, were memorialized. All are gone except for files in the Carnegie Museum.

Sports and music loomed as large, if not larger, in the Hill than in the white community. Naturally all of the national boxing and baseball greats visited, including Joe Louis, Jackie Robinson and Willie Mays. Thanks to his numbers empire which back in the thirties was taking in $25,000 per day and employing 500 people out of a barber shop front, Gus Greenlee was literally the RK Mellon of the Hill District. Afterall, major Pittsburgh banks wouldn’t touch the place. He also built a ball park in 1932 for his Pittsburgh Crawfords, one of two Pittsburgh Negro League baseball teams , the other being the Homestead Greys. In the thirties he also bought the block-long Masio Hotel which featured indoor golf. He renamed it the Crawford Grill complete with a first-floor bar and elevated stage with mirrored piano, a second floor with a theater and revolving stage, and then a third floor housing the private Crawford Club featuring gambling for white and black patrons. National talent, including Duke Ellington was attracted to the place. The Crawford Grill also spawned local, soon to be national, talent like Billy Strayhorn, Billy Eckstein, Earl Father Hines, “Little Georgie Benson” and a singing daughter of a numbers runner named Lena Horne. Yet signs of any life, let alone that life are long gone. A desolate skeleton remains.

Using a side street I crossed the Hill District avenues in a northerly direction: Wylie, Webster and Bedford, over to what was once playwright August Wilson’s neighborhood. The scene was much the same. Proceeding up a hill to the corner of Webster Avenue and Erin street, I came across a hulking mass of a building, blackened and choked by overgrown vines. Beneath a domed-roof can be seen a Jewish Star of David above the entrance. Like a number of other buildings, as the Jews moved from one hill to another, synagogues became churches; in this case Zion Hill Baptist church in 1956. Undoubtedly, this once-elegant edifice promises to be reduced to broken brick fragments and eventually grass.

Driving ever upward, I ended up in a graveyard. How appropriate.