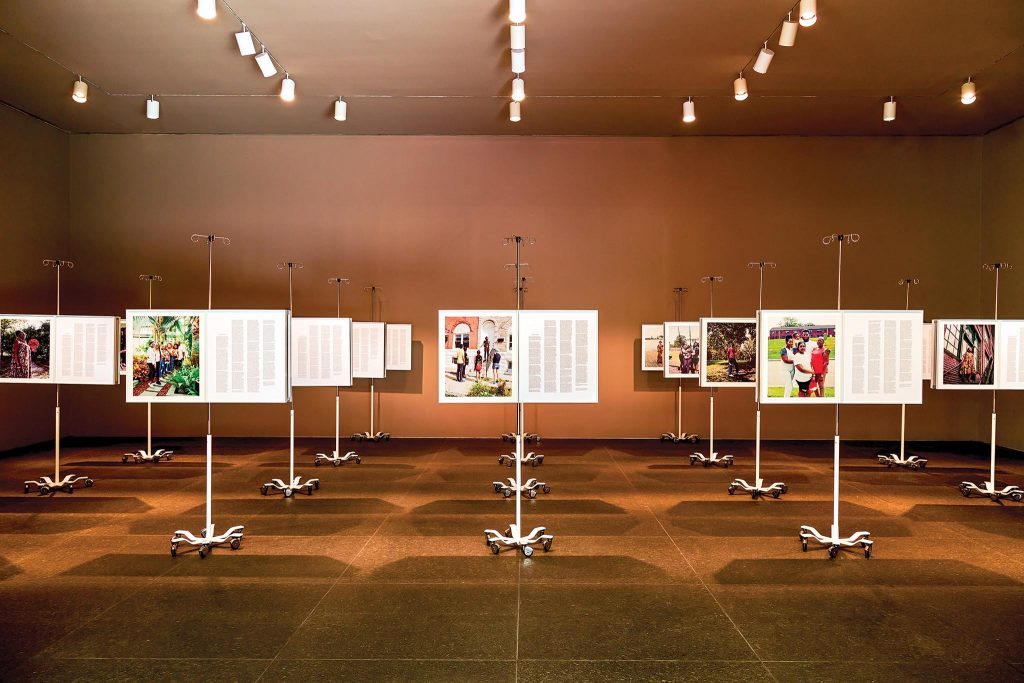

The latest iteration of the Carnegie International dropped in the era of the pandemic. What would it say about our world situation as reflected in the work of contemporary artists? How would it fit within the historic framework of the exhibition that has been instrumental in shaping the character of the Carnegie Museum of Art?

The first question the exhibition raises is the nature of what we mean by the terms “contemporary” and “international.” Although this long-running exhibition is now called the Carnegie International, it was started in 1896 by founder Andrew Carnegie to prove that American art was just as good as the more recognized European art. For most of its history, it has included primarily western art, but it has become much more international in scope in recent years. That path continues in today’s 58th version.

While this year it presents many more artists than usual, it has the smallest-ever number of American and European artists balanced with much larger contingents from the rest of the Americas and various parts of Asia. Rounding out the list is the growing number of diaspora artists who have moved from their homeland to art capitals primarily in Europe and the U.S. Different voices have been raised, with many artists showing here for the first time.

This realignment responds to the growth of and access to the larger international world, the disruption of established hierarchies privileging the West, a continued search for the new, and inroads made by non-Western curators. Sohrab Mohebbi, the International’s first non-western curator, was raised in Iran (B.F.A. in photography) but lives in the U.S., where he earned an M.A .from Bard College’s Center for Curatorial Studies. With a foot in more than one place, his world view diverges from previous organizers who relied heavily on international advisors. His team widens the purview with two curators who have worked at several international venues, and advisors who hail from Saigon, the Philippines and Southeast Asia, Sao Paulo, Hong Kong, Guatemala, Amsterdam, Dakao, Nairobi, and San Francisco. As a result, many of the selected artists are not the names that appear in most of the large surveys, thus bringing a freshness and sense of discovery.

This global point of view has been expanding in the past several decades. Many still remember the Paris exhibition Magicians of the Earth that replaced the city’s traditional biennial in 1989. It was seen as a response to the groundbreaking, controversial Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1984. While the MoMA show dealt with the influence of so-called “primitive” art on the development of modern, western art, Magicians redressed the balance with half the artists from the West and half from elsewhere.

This year’s International is a descendant of that show with its plusses and minuses. The juxtaposition of work by artists with advanced studio art degrees who are steeped in critical theory with artists more interested in experiences, can produce a disconnect that is difficult to bridge. For example, Ēdgar Calel draws on his Guatemalan heritage in his piece “Oyonik” (The Calling) from 2022. He arranged pottery vessels filled with water and flowers on the floor because water is considered a conduit to communicating with people who are deceased or far away. This connection to beliefs represented in rituals is hard to reconcile with the work of Anh Trân, who examines the language of abstract expressionist painting. These oppositions parallel discussions about the relationship of art and craft, design and/or function.

One possible solution is to use a theme, such as nature or spirituality, so that the works share a commonality, allowing for the differences to be recognized but not necessarily judged according to still prevailing hierarchies. The International has, for the most part, stuck to the survey format, but in 2008, there was a stated theme, “Life on Mars,” that asked what it meant to be human in the contemporary world. In two other recent versions, the 1988 and the 2004, themes emerged subconsciously as the former was inhabited with work revolving around an end-of-millennium malaise, and the latter focused on the ideas about the ultimates as defined by philosopher Immanuel Kant.

The current exhibition supposedly doesn’t have a theme; indeed, curator Mohebbi calls the organizing principle a way to situate the discussion, a point of view, an approach or, as he calls it, a “catchphrase.” That is a matter of semantics, as this version is obviously political in nature and intent. Mohebbi discusses the “emancipatory potentiality” of art with its capacity for reconstitution and resistance, choosing artists who emphasized a critique of entrenched politics and the desire and need for change. This show becomes part of the continuing dialogue about the relationship between art and political commentary and/or social activism. It’s the art of resistance or, conversely, the resistance of art. Political commentary has been part of the contemporary art scene for a long time now and has been present in almost every International since the 1980s, but this year it dominates the show. The emphasis on issue-based art over aesthetics is timely in our increasingly divided world.

This International deals with human rights issues — predictably, the war in Vietnam, human rights violations, health workers and accessibility during a world pandemic, migration, the environment, the economic haves and have nots, etc. What changes the discussion here is the inclusion of artists from more places around the world, bringing many other inequities to our attention. The color photographs of bucolic ponds in Cambodia by Vandy Rattana (born in Phnom Penh, lives in Taipai) ignore their troubled history of recovering from toxic poisoning from U.S. bombs, while Thu Van Tran (born in Ho Chi Minh City, lives in Paris) stains the walls of the Hall of Sculpture with ethereal frescoes by mixing the color-coded hues of chemical warfare that left a stain in Vietnam. Soun-Gui Kim (born in Buyeo, lives in Viels-Maisons) combines real-time global stock market indices and videos from food markets as a comment on the effect of capitalism in projections onto the floor and passing visitors. And in one of the more exuberant pieces, Banu Cennetoğlu (born in Ankara, lives in Istanbul) installed 10 balloon bouquets made of letters from the alphabet in the classically inspired Hall of Sculpture. Each set of gold letters, if assembled in sentence form, would spell out one of the tenets of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights released by the United Nations issued in 1948. Sited in homage to Greek culture and democratic ideals, the balloons will deflate during the run of the show, reflecting the impossibility of adhering to these newer ideals. Entitled right?, this work adds a light touch in an otherwise somber and sober show, yet how many will understand it?

These are a few examples in a show that sets an agenda of dealing with issues associated with the influence and acts of the United States. In his essay, Mohebbi proclaims the stage for the work in the show as an examination of the kind of world the U.S. attempted to bring into existence politically and economically as well as culturally and in terms of lifestyles post World War II. His two main examples show the consequences of the war in Vietnam and the building of the Panama Canal, assigning blame for resulting destructive consequences to the U.S., when the actual history is much more complicated. In turn, the work included rests primarily in the political arena, leaving aside the impact of cultural exportations, especially the fantasies of the Walt Disney Company. The influence of the U.S. as a superpower in the last century is an enormous subject, too large and complicated for one single exhibition, leaving viewers with a less than fully interrogated narrative.

The concentrations outlined in the catalog and evident in the exhibition lead to two more concerns. What is the relationship between the desire to express the need for systemic change and an interest in the aesthetic in works of art? This show is strangely flat and distant despite the potent subject matter with many viewers probably left confused, a marked change from the last International that seemed to elicit emotional responses. Labels are necessary to understand the importance of much of the work, and the aesthetic seems to be downplayed all too often. Rafael Domenech (born in Havana, lives in New York) designed an ellipse (a symbol of exile as a non-centered structure for the artist) as a site for performances. It is misplaced in the outdoor sculpture courtyard, its bright red and blue a harsh contrast to a space designed to bridge the gap between the old, neo-classical building with the modern style of the 1974 addition of the art museum. That disconnect stops any interest in the meaning of the work.

The other concern raised by the “catchphrase” is the overwhelming number of works within the show and the decision to include historic works alongside contemporary ones. While Mohebbi uses a definition of “contemporary” as the dialectic between a center (government, institution) that is responsible for happiness and yet relies on surveillance to control the population, most still think of it in terms of time periods. Yet Mohebbi and his team have chosen many works of previous generations. Kate Millett, the acclaimed feminist author, for example, is represented by sculptural cages made in 1975. For her, cages were actual prisons as well as metaphorical ones, devices designed to subjugate people and ideas, a parallel to surveillance tactics.

The successful pop artist Claes Oldenburg is represented by a poster he designed as a call against U.S. intervention in Central America as part of a 1984 campaign that united efforts by several art and political collaboratives in the Americas. Both show the continuing interest in political gestures made by artists but call into question what has been included and what excluded. Why, for example, use Oldenburg but ignore the activist leanings of Nancy Spero and Leon Golub? It’s funny how this strategy to add a historic context to a particular theme is unconvincing here, actually adding a degree of confusion and a sense of fatigue while a similar strategy enhanced the curated show “The Milk of Dreams” at this year’s Venice Bienniale. Then again, the latter was rooted in the imagination with work that was more poetic and open-ended.

Resistance, as privileged by the curatorial team, is as complex as our contemporary situation. It raises questions about the role of art and artists in changing the realities of our world. How can they help us envision a different future by pointing out the problems of the past and the present? Is that possible or desirable in the world of art and what happens to our concept of art in the process? Is beauty a thing of the past?

This International is ambitious, sprawling, and info-centric, but it is grounded in the past in ways beyond the contours of the show. Dia al-Azzawi (born in Baghdad, lives in London) excavates the ruins of Mosul and Aleppo in a map-like presentation, following in the footsteps of artists such as Kathy Prendergast and Zarina who have mapped contested areas. This exhibition and this kind of work begin the process of peeling away the many layers of the onion. As the motivating phrase for the exhibition — “Is it morning for you yet?”— implies, answers depend upon our experiences, histories, realities and subjectivities, with some unexpected similarities but also some alarming differences.

Everything is relative, from the curator’s approach and intent to the artists’ interpretation to the understanding of the viewers. At the very least, this International brings more disturbing situations to a greater audience, quite literally performing its educational underpinnings.