It Turns Out, the U.S. Really is Exceptional

“America, you are better off than our continent, the old.” – Goethe

Previously in this series: On Agency, Part VIII, America – Where Agency Flourishes

Last week we observed that the vigorous human agency of the American colonists allowed them to defeat a powerful antagonist – the combined forces of France and numerous Native American tribes. A few years later that same remarkable agency was employed to defeat an even more powerful foe – Great Britain itself.

But it wasn’t until the United States of America was officially established that the potent agency of the nation began to astonish the world. Unlike anywhere else on the planet, protection of human agency was hard-wired into the American Constitution – the world’s first – especially in the Bill of Rights. Freedoms that had been mainly traditional in England (especially as regards the common people) were now spelled out in detail.

In addition to those freedoms, so determined were the Framers to protect human agency from the terrifying power of the State that many – some would say way too many – structural features were included in the Constitution to ensure that the central government would not degenerate into tyranny.

There would, for example, be no king in America (an impossibly radical idea at the time) and the President that substituted for the king would be elected – indeed, would have to be reelected every four years. Legislation, even if passed by both houses and signed by the President, could be invalidated by the Supreme Court – an unelected body serving life terms.

While the House of Representatives reflected the differing populations of the states, the Framers were keenly aware that dictatorship by the majority was an ever-present danger. Therefore, the Senate was designed to represent the states evenly. Francis Fukuyama recently calculated that, in an extreme case, senators representing only 16 percent of the U.S. population could block legislation. The Framers would be proud.

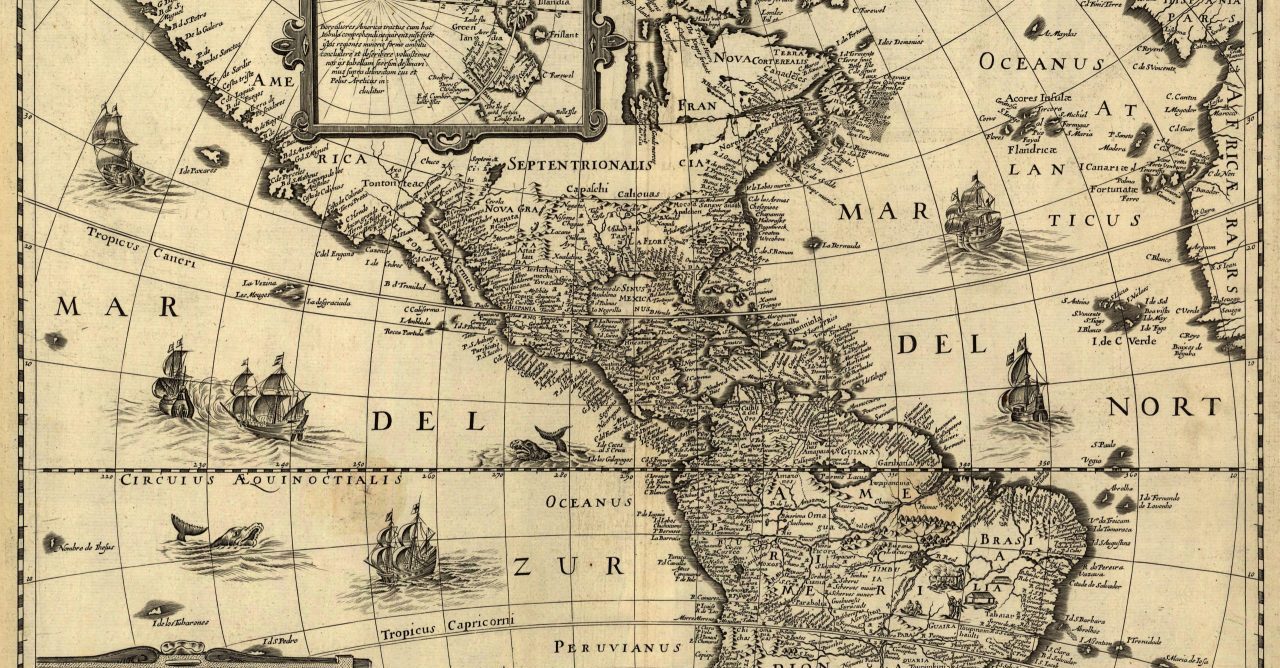

In 1800, the tiny United States of America, a few polities huddled up against the Atlantic Seaboard, boasted a population of five million people. This made the USA about the same size at the time as Siam and Morocco, and smaller than Iran, the Kingdom of Naples, or Vietnam. The U.S. was roughly one-tenth the size of France, Britain, and the Holy Roman Empire, and was one-fiftieth as large as China and India.

But the world was about to amazed at the power of human agency unleashed. In the 1860s, barely seventy-five years after the U.S. was formed, the two most powerful armies in the world were both American. Two decades after a terrible Civil War America’s economy had surpassed that of the United Kingdom, and by 1890 the U.S. was the largest economy in the world, surpassing China.

So desirable was the freedom offered by America, and the economic opportunities afforded by the huge human agency in the country, that millions of people wished to migrate to this magical new land. Starting from almost nothing, America eventually became the third most populous country in the world (out of almost 200).

Far more important, America became one of the only very large countries in the history of human civilization (and the largest) to become wealthy on a per capita basis. Countries with huge populations can easily generate high GDP on an aggregate basis, but creating per capita wealth on that scale is a very different matter.

Here, for example, are the five largest countries in the world today by population (not counting the U.S.), and their per capita GDP as a percent of America’s:

China = 16%

India = 3%

Indonesia = 6%

Pakistan = 1.5%

Brazil = 11%

Over the two centuries of America’s existence the country has faced many competitors for dominance. The first and most formidable was Britain itself, whose human agency was most similar to that of the U.S. But as noted above the U.S. surpassed Britain economically by 1880, and America became the most powerful country in the world after World War I.

But after Britain no country ever came close to surpassing the U.S., for the simple reason that those nations possessed far less agency.

Consider the Germans who, notwithstanding their defeat in two consecutive world wars, rose again after World War II. Many observers believed Germany’s “Economic Miracle” would allow it to surpass the U.S., due mainly to the famous German discipline. It didn’t happen.

Japan was next. The ability of the Japanese people to work cooperatively for the common good, to seek consensus, seemed certain to outcompete America’s radical individuality. But that didn’t happen, either. Instead, Japan has endured three decades of economic stagnation and, last I looked, the U.S. economy was four times that of Japan.

After that it was the USSR. Economist Paul Samuelson infamously predicted that the Soviet economy would surpass that of the U.S. by 1984: “The Soviet economy is proof that, contrary to what many skeptics had earlier believed, a socialist command economy can function and even thrive.” The USSR certainly boasted high collective agency, but its very low individual agency doomed it to collapse only a few years after it was supposed to surpass America.

As noted, America’s only serious challengers have all fallen by the wayside because they lacked the radical individual agency of the U.S. and, in the long term, simply couldn’t compete. Collective agency can accomplish great things in the short term, but over the long haul the evidence suggests that it doesn’t hold a candle to individual agency. China take note.

My thesis in this series of essays has been that societies with higher individual agency outcompete societies with lower individual agency. We observed this outcome in China and now we have observed it in the case of the world’s highest-agency country, America.

Next week, though, I’ll quit with the American triumphalism and instead we’ll ask ourselves this question: Can individual human agency go too far? What might stop it in its tracks?

Next up: On Agency, Part 10