Charming and Impossible

Stefan Lorant was a dashing, debonaire fellow when he was young, and even in his late old age he remained attractive to women. One 40-year-old divorcée recalls having an affair with Lorant when the latter was in his eighties. “He was impossibly romantic,” she told me.

Previously in this series: Stefan Lorant Part II, The Book On Pittsburgh

Another woman, Rosemary, emailed Lorant’s biographer, Michael Hallett, explaining how she had fallen desperately in love with the 93-year-old Lorant in 1994, shortly before he died. Rosemary was in her thirties.

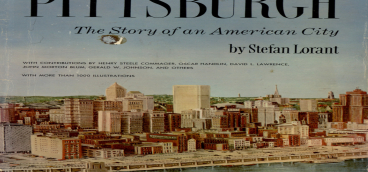

As the fifth edition of Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City began to take shape, the production team was Lorant, Bruce and Gail Campbell, and me. I was “Chairman of the Editorial Board,” but Bruce and Gail did most of the work, writing a final chapter for the book and updating the massive chronology at its end.

That chronology began in 1717 and went right up to the (then) present, sometimes representing an almost day-by-day history of the city. It seemed to me an odd way to end a book – an 85-page, fine print chronology – but in fact it has been a huge boon to urban historians.

My job, really, was to ride herd on Lorant, which turned out to be like riding herd on a thousand angry water buffaloes. When he came to Pittsburgh his days were a whirlwind of activity, meeting with potential funders in the foundation community, cajoling CEOs of major corporations to commit to buy his book, hobnobbing with Pittsburgh’s powerful and the merely glittering.

Lorant could be the most charming man in the world or the most impossible person you had ever known – sometimes in the same sentence. If he liked you or if you were interested in his book, he was all charm. If he thought you were a fool, or you didn’t appreciate the brilliance of the Pittsburgh book, he could be almost violently rude.

Lorant hated book publishers, among other assorted people. The first edition of the Pittsburgh book had been published by Doubleday, but Lorant was so enraged by the firm that all the subsequent editions were published privately – and Lorant’s profits accordingly went way up.

As one of Lorant’s wives wrote, Stefan’s “judgment of ability was unerring,” but the flip side was that he simply could not suffer fools. And Lorant believed that every charitable foundation president, like every publisher, was a congenital fool. (This was probably because they tended to turn down his grant requests.) As he and I made the rounds of Pittsburgh’s larger foundations, I did my best to convince Lorant to be his charming self, but this proved to be hopeless.

On one occasion we were sitting with the long-serving, self-important president of a very large foundation, and the fellow was paging through his own annual report, regaling us with the size and diversity of his grantmaking. He said, “What do you think, Mr. Lorant? Impressive, no?”

Lorant leaned toward the fellow and said, “Why would you waste good money on that [rhymes with ‘bit’]?”

On another occasion, as we were leaving the office of a foundation, but were still well within earshot, Lorant said to me, “Is that lady a complete idiot or am I missing something?”

Needless to say, raising money for Stefan’s book was a challenge. In addition, I had to constantly remind him that I was a foundation president. To which Lorant invariably responded with an airy wave of his hand, saying “Pffft!”

There were so many weird episodes involving Lorant that I could write a book about them. But for purposes of these essays, I’ll just mention a few of my favorites. I’ll call this episode:

The Penthouse Suite

When Lorant visited Pittsburgh he insisted on staying in the penthouse suite at the old Pittsburgh Hilton, located at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, where the Ohio River begins. If the penthouse suite wasn’t available for some reason, Stefan refused to come to town until it was.

On one of his trips I had dutifully reserved the penthouse suite for Stefan, but shortly after he checked in, my assistant, looking deeply alarmed, stuck her head in my office and told me that “Mr. Lorant is on the line and he’s very upset!”

I sighed and picked up the phone. Stefan was hollering so loud I couldn’t at first make out what he was saying. Then I realized he’d lapsed into Hungarian, his native language. “Speak English!” I shouted into the phone. “Eh? Oh!” he said, somewhat calming down.

The problem, I learned, was that the penthouse suite had a small library in the living room, with most of the books being about Pittsburgh or Pittsburghers. But Lorant’s Pittsburgh book wasn’t among them.

This was plainly impossible, as I had personally checked the library in the penthouse suite that very morning and the Lorant book was there. Still, I dropped what I was doing and headed over to the Hilton and up to the penthouse. When Lorant opened the door he was on the phone with the hotel’s assistant manager, complaining loudly about the oversight. “You are all fools!” he was shouting into the phone.

I took the phone away from Stefan, apologized profusely to the poor assistant manager, who seemed traumatized, then hung up and glared at Stefan. “You terrified that poor woman!” I said to him, to which he responded, “Pffft!”

I turned to the bookcase, saying to Stefan, “You were just looking on the wrong shelf.” I went to the correct shelf but, to my amazement, Lorant’s Pittsburgh book wasn’t there. “You see!” he shouted, “You see!”

I called the long-suffering assistant manager back and asked if perhaps someone had removed the book since I’d last seen it earlier that morning. She promised to check with the housekeepers and call me back. Just in case, I called my assistant and asked her to track down another copy of the Pittsburgh book and bring it over.

Having now more or less turned the city upside down on Stefan’s behalf, I said to him, “May I use your bathroom while we wait?” I walked into the bathroom and there was the Pittsburgh book, sitting on the floor beside the toilet, exactly where Lorant had left it.

Next up: Stefan Lorant, Part 4