I first got interested in John Kane 20 years ago. I was working at The Heinz Endowments, the large charitable foundation in Pittsburgh, which has a wonderful collection of the work of Pittsburgh artists, going back over 100 years. A local art dealer named Pat McArdle was talking to me about the collection when he said:

“It’s a shame you don’t have a Kane.”

“A what?” I replied.

Pat patiently explained John Kane to me — why his work is so important in the development of 20th Century American art, and why his character is so interesting and so very Pittsburgh. I was hooked, and I immediately began gathering research on Kane and thinking about him as a subject.

I learned that, though Kane had been nationally famous 100 years ago, over the decades since his death he has become largely forgotten, even in Pittsburgh. I thought about his importance, and the extraordinary picaresque journey of his life: Kane was born in Scotland, emigrated to America in 1880 at the age of 20, and immediately headed for Pittsburgh, the Mecca for laborers in the 19th century. There Kane worked every job imaginable, from steelworker for Andrew Carnegie to coal miner for Henry Clay Frick to street paver, bridge builder, house painter, carpenter, construction worker—all the while gradually building his skills as a sketcher and then a fine-arts painter.

Late in Kane’s life, about the time most people are retiring from work, the artist became internationally famous when his work was admitted to the renowned Pittsburgh art competition known as the Carnegie International. Suddenly, John Kane’s work was being purchased by wealthy art collectors and major American museums.

As I dug into this fascinating journey of a life — so little remembered now in Pittsburgh — I realized that someone needed to do something about Kane’s exceptional legacy. Some years later, when I finally got down to the job of fashioning a life story of Kane, I hit a wall: it was time to write trenchantly about the man’s art, try to unpack the meaning of his life through a careful critique of his work. I had no experience, no capability for writing the art history and the art criticism that I knew was essential to the book.

by Maxwell King

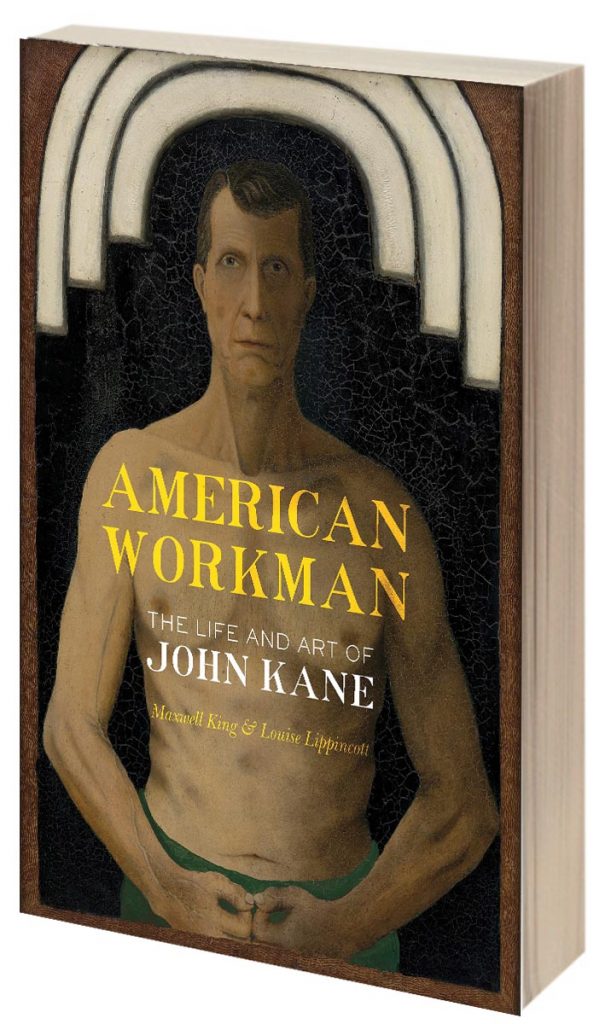

University of Pittsburgh Press ($40.00): John Kane titled this painting Seen in the Mirror for a 1928 exhibition, and John Kane in the Looking Glass in 1931. John Kane, Self-Portrait, c. 1929. Oil on canvas over board. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund, Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

Luckily, there was an answer. I knew Louise Lippincott from the Carnegie Museum of Art, and I knew that in her years as an important curator there she had been a key steward of the largest Kane collection in the world, a dozen and a half paintings and many drawings the museum amassed over the years. And she knew a great deal about all the other Kanes out there: in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Whitney Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, The Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg, and other museum and private art collections.

Also, Lulu has a reputation as a tough, focused intellect, just the sort of critical mind I needed for the project.

The timing was right: Lulu was recently retired from the Carnegie, and she was harboring nagging doubts about whether she had done as much with Kane’s legacy as she might have done. So we set out to work together: me on the biography and Lulu on the art history and criticism.

As we moved forward, Kane’s unusual character took shape for each of us. First and foremost, he was a tough guy: a barroom brawler, a heavy drinker all his life, an almost-nomadic laborer who left his family for long periods of time while he worked every industrial job of the time — even after he lost a leg in a train accident. And he was a dogged worker who wouldn’t give up on a job until he had mastered it.

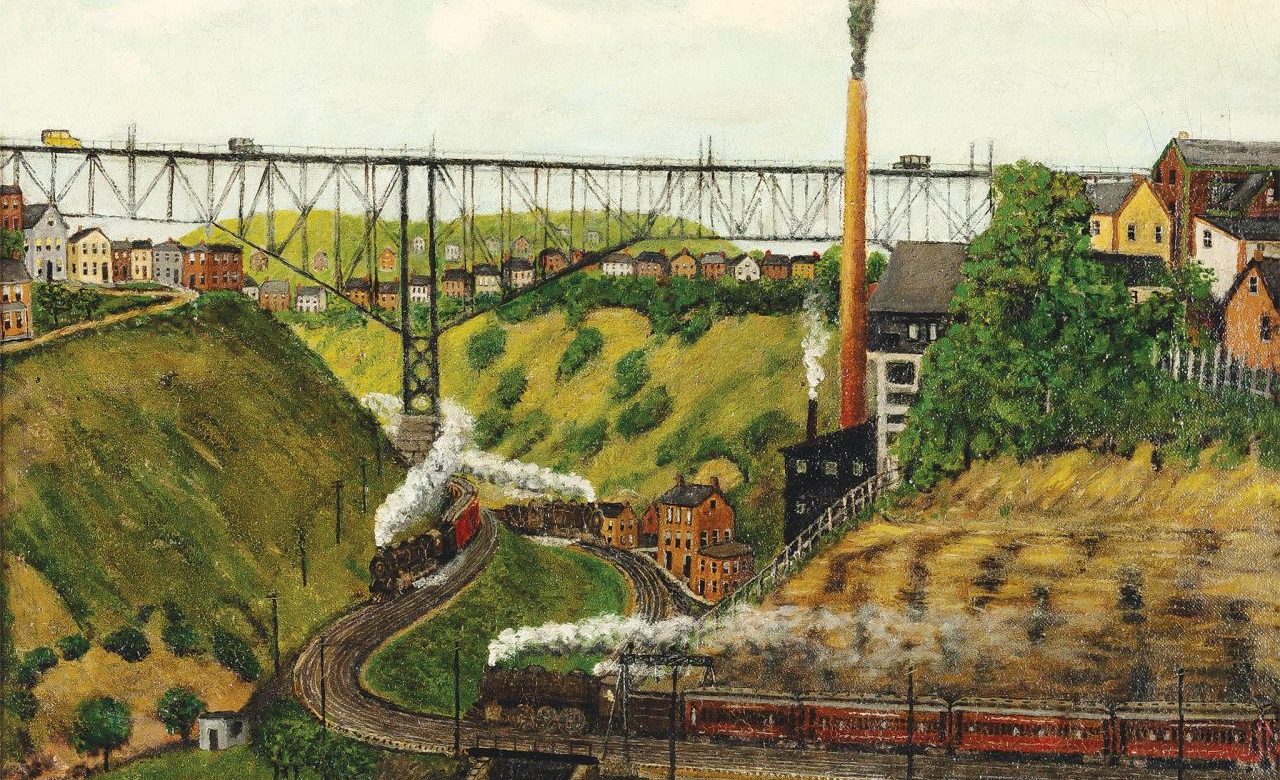

But there was something else: the persona of a sensitive, romantic artist who, increasingly, loved beauty and turned to his art to express his very distinctive perspective on his adopted hometown. He saw beauty in his everyday surroundings — the hills and valleys, rivers and bridges and small towns, industrial mill buildings, riverboat tows and railroad trains. And he evolved an art that yielded a wonderfully detailed and evocative portrait of a city and region he came to love. In effect, Kane became to Pittsburgh what Grant Wood became to Iowa: an image maker.

Eventually, Kane became the pre-eminent artistic chronicler of Pittsburgh landscapes and its character. And he had a great influence on the evolution of American art in the 20th century, which is why he remains a feature of so many museum collections. But what really set the hook for me was the realization that this native Scotsman had become an extraordinary exemplar of the Pittsburgh character: tough, hard-working, no-nonsense, unpretentious, intensely focused and devoted to the community.

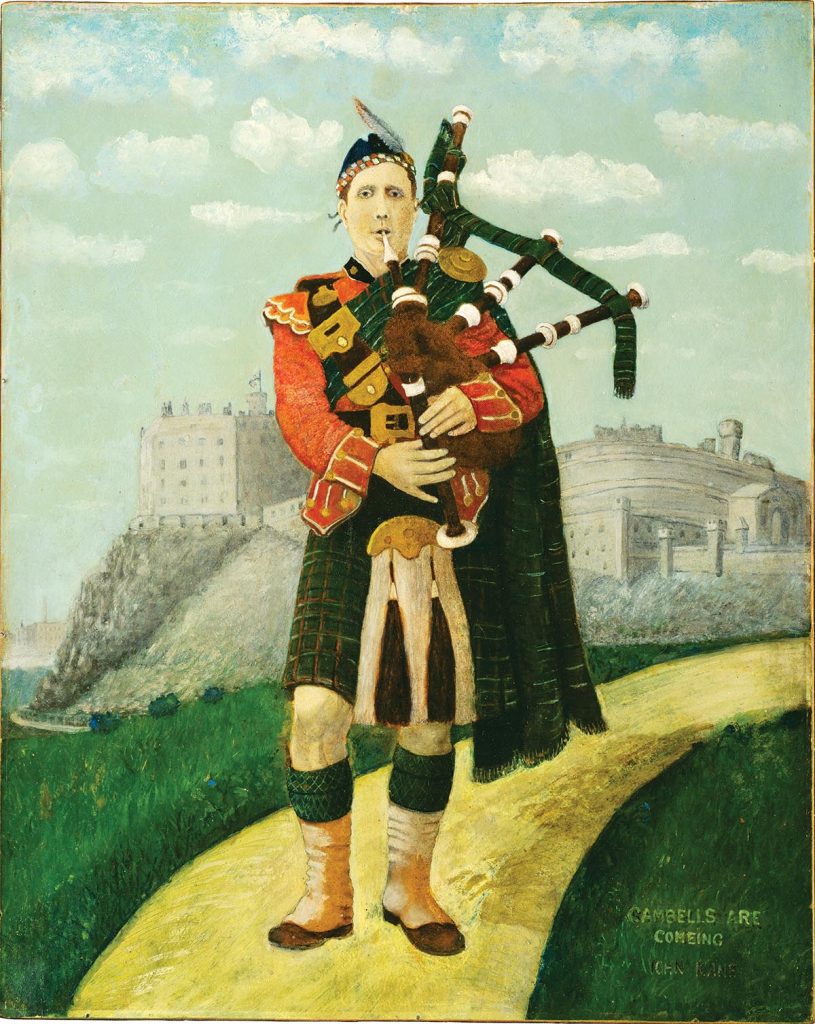

John Kane’s 1932 painting is in part a tribute to his beloved brother Patrick; like many Kane works, it was drawn from a combination of postcard images and memory. Oil and gold paint on paper over composition board. The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection. Museum of Modern Art, NY. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Think about it — Pittsburgh is famous as an entrepreneurial center of hard work and creativity. Industrialists such as Carnegie, Frick, Heinz and Westinghouse drew praise for their innovation, and their workers became world famous for their productivity. Sounds like John Kane personified.

The Pittsburgh region also has a long history of reinventing itself to overcome economic difficulties: frontier town, gateway to the West, center of armament production for the Civil War, crucible of American steel, key to the war efforts of both world wars, and, most recently, a renaissance built on tech, universities and foundations. Kane spent a lifetime reinventing himself through a series of crafts, a part-time career as a boxer and, finally, as one of America’s finest artists.

It seemed logical that Kane and Pittsburgh would become so intertwined — and that his legacy should be brought back into focus. But, now that we had the beginnings of a book, we needed a publisher. We went to see Peter Kracht, director of the University of Pittsburgh Press, and had an immediate meeting of the minds. Kracht could clearly see the potential of a book that might resurrect so much exciting Pittsburgh history.

In fact, he substantially changed the direction of the book through his critique of an early draft. It’s a good story, he said, and you’ve captured the man. But where is the context, where is the Pittsburgh history through which Kane lived and prospered? I went back into research mode for five more months, and the result was a much stronger, richer narrative. Eventually, the book — American Workman, the Life and Art of John Kane — became something of a revisionist history, telling the story of Pittsburgh’s great industrial era from the perspective of the workingman rather than the titans of industry.

The next challenge was pictures. We wanted lots of Kane’s work, of course, but Lulu’s research also unearthed a trove of historical pictures that revealed Kane’s living environment. To print scores of pictures, and to have them appear throughout the text, not grouped in a centerfold, would significantly increase the cost of the book — as would high-quality paper to show the art to best effect.

John Kane, 1934. Oil on canvas. Gift of H. J. Heinz Co., Museum collection, Senator John Heinz History Center, Pittsburgh.

Fortunately, Pitt Press was able to get small grants from The Heinz Endowments and the Sheila Reicher Fine Foundation to support the presentation of art. The result gives the reader access to images exactly where they make the most sense in the text.

For Lulu and myself, transplanted Philadelphians who have found ourselves deeply in love with the character of Pittsburgh, the book proved to be a wonderful way to connect to our adopted region, just as Kane had decades earlier. And so we decided on a dedication that might capture the spirit of this:

“For all the working men and working women who have made John Kane’s Pittsburgh the very real, gritty and beautiful place we love.”

(An exhibit entitled “Pittsburgh’s John Kane: The Life & Art of an American Workman” runs through Jan. 8 at the Heinz History Center. Another Kane-related exhibit, “Gatecrashers: The Rise of the Self-Taught Artist in America,” will run at The Westmoreland Museum of American Art from Oct. 16-Feb. 5.)

Maxwell King is the former editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer, author of the poetry collection “Crossing Laurel Run” and the New York Times bestselling biography “The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers.”