An Overdue Obituary – The McKeesport Daily News

When I was growing up in Elizabeth, a small town in the Mon Valley, and uncles, aunts and neighbors learned that I wanted to write for a newspaper, I would hear this common refrain: “Maybe you can work for The Daily News.”

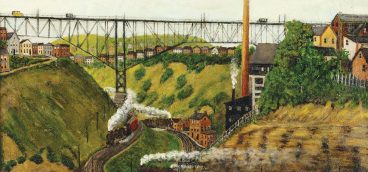

Although my sights were set elsewhere, I knew their words were less about me and more about the devotion they had for their chief source of news and information, the McKeesport Daily News. Between 1884 and 2015, the paper reported almost everything that happened in one of the nation’s premier industrial corridors. For most of those years, steel was poured, cast and shaped from Duquesne to Donora, businesses thrived between Homestead and Charleroi, and families raised on money from the mills filled the streets and houses of every hill and hollow. Besides livelihoods rooted in steel, Mon Valley people had one more thing in common: A portrayal of the world and their little towns in the pages of The Daily News.

From my house in Elizabeth in the ‘60s and ‘70s, you could see the white smoke billowing from the Clairton coke plant, where my father worked. The Daily News hit our front porch six days a week, Mondays through Saturdays. Since the paper had no Sunday edition, subscribers got The Pittsburgh Press on Sundays instead.

As comprehensive and engaging as “the city paper” was, it didn’t cover the range and depth of hometown life that appeared in The Daily News. Starting with the decisions of Braddock Council or some new construction on the Glassport Bridge. The kind of football season facing the McKeesport Little Tigers or the list of stores coming to Eastland Mall. Who the new officers were at Holy Trinity’s Christian Mothers. When Slovak Day was happening at Kennywood Park. Why taxes were going up in Belle Vernon. What time the steelworkers’ picnic would begin.

The paper chronicled the major events of the day — wars, elections, the World Series — with some of the same national wire reports carried by the Press and Post-Gazette. But unlike the metro papers, The Daily News trained its mirror on ground level every day: Lysle Boulevard, Monongahela Avenue, Walnut Street, Lebanon Church Road — places the Pittsburgh papers helicoptered into only for that rare, big story.

Plus, everybody in the Mon Valley knew someone who had made it into The Daily News. I had my own cameos in those pages: a photo of me with two fifth-grade classmates after we’d won a World Book Encyclopedia set for St. Michael’s Elementary School; a picture of me and other officers of the Serra High School Student Government; and the first time I ever saw my name in a newspaper, at age 9 — listed as a survivor in my father’s obituary.

In the course of its 13-decade life, The Daily News rose and fell with the fortunes of steel. At its zenith in the 1970s, the paper had a circulation just under 50,000 — the sweet spot for any community newspaper. Small enough to be close to (and treasured by) its region; large enough to have the reporters and resources to cover it well. By the time 2016 dawned, however, The Daily News was no more.

How Citizen Gatekeepers Can

Save Local Journalism

by Andrew Conte

University of Pittsburgh Press ($26)

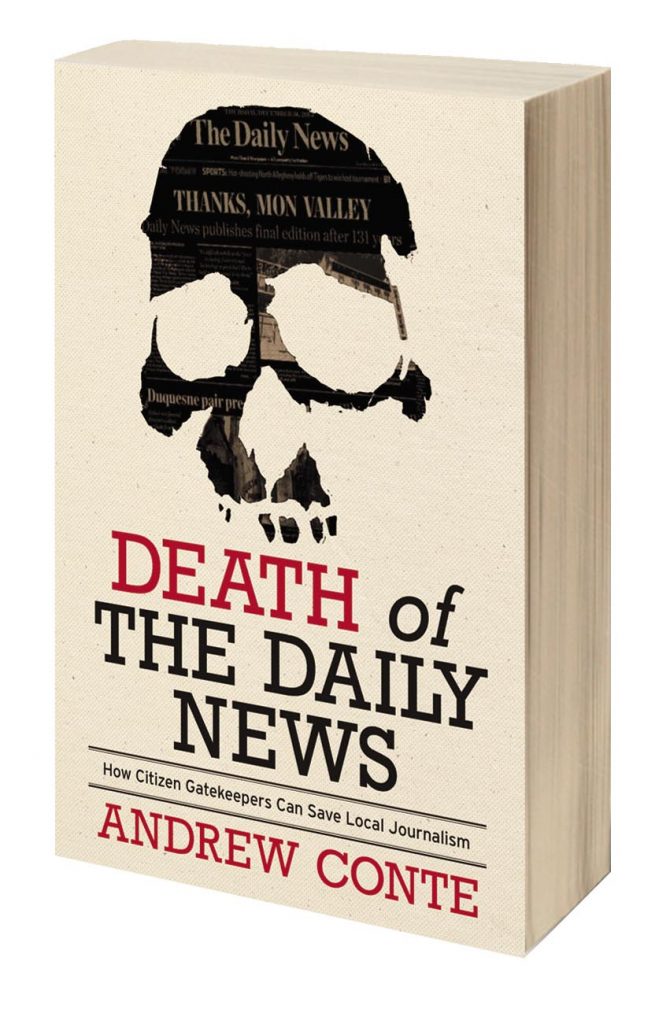

The paper’s success, demise and ensuing void is the subject of a fascinating book recently published by University of Pittsburgh Press. In “Death of The Daily News: How Citizen Gatekeepers Can Save Local Journalism,” Andrew Conte examines the decline and disappearance of newspapers around the country and, through the prism of the late local publication, shows how a news desert can suddenly envelop a community. The founder of the Center for Media Innovation at Point Park University and a former investigative reporter with the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, Conte uses his skills as a journalist and academic to tell two compelling stories.

One is the national overview, in which more than a quarter of all newspapers have closed since 2004 and the number of journalists has dropped by half since 2006. That means the loss of not only tens of thousands of reporters and editors but also the “gatekeepers” among them who decide which stories to present to readers on a daily basis. Conte goes to great lengths to explain the essential role of the professional gatekeeper and contrasts that with so-called citizen journalists who post news and information to social media without standards, accuracy or sometimes even facts.

The other, more readable, tale is how people in the Mon Valley have struggled after the loss of their beloved Daily News.

“The death of the newspaper also meant a loss of civic awareness for residents and community leaders, as they lacked an institution committed to chronicling city meetings, police and fire incidents, and civic events such as annual festivals, church gatherings and school pageants,” Conte writes. “The newspaper told the minutiae of daily life — the negative things that happened with the economic collapse and increase in crime but also the moments that helped people see how their actions fit into a larger narrative.”

Colleen Denne, the former director of the Carnegie Library of McKeesport, says in the book that a common bond died with the newspaper: “I feel like The Daily News kept this whole area feeling like they were the community, you know like the sense of community between all the areas it served. We were all the focus of The Daily News and I think we all felt like we were one area.”

McKeesport’s mayor says that while he had his run-ins with Daily News coverage, he missed it when it was gone because the paper covered positive developments as well. A state legislator agrees: “While I’m sure some elected officials look at media and journalists as a pain in the ass, in some ways they are our friends in this business.”

Then there are times when you shouldn’t believe something until you read it in the newspaper. Conte reports that the word around McKeesport was that a well-known businessman named Ray had died. At Di’s Kornerstone Diner, a friendly hangout in Olympia Shopping Center, the waitresses, the customers — everyone was gabbing about it. Until Ray himself walked into the restaurant one day. Talk about living in a news desert. You know that’s the case when you lose the obits.

Conte tries to hold out hope, though, as expressed in the book’s subtitle “How Citizen Gatekeepers Can Save Local Journalism,” and he has even worked beside other journalists on a relatively new project called the McKeesport Community Newsroom, set in The Daily News’ old Art Deco building. He says that prior to the pandemic more than a dozen people, between age 16 and 75, showed up every other week to talk about story-telling, photography and other elements of good journalism.

While those are worthy skills to be learned, and the mentors should be commended for helping citizens develop them, it will take much more to replace the steady, comprehensive output of a newspaper such as The Daily News. The solution, if there is one, to America’s disappearing newsrooms, may be found in the book’s epilogue.

Conte recounts that in the summer of 2021, a small newspaper in Monessen, 19 miles upriver from McKeesport, was in search of new quarters. The upstart Mon Valley Independent, which printed its first edition in May 2016 and turned a profit three years later, decided to move half a dozen reporters and editors into the former Daily News building. The personnel shift also signified a major expansion in coverage.

By finding their own formula for success and paying professionals who are accountable to their colleagues as well as their readers, ambitious new papers such as the Mon Valley Independent stand a better chance of replacing the civic glue that was The Daily News. They are also more likely than an ad hoc crew of social media posters to get the facts right. Even Ray, who is not yet dead, would agree.