A farm life

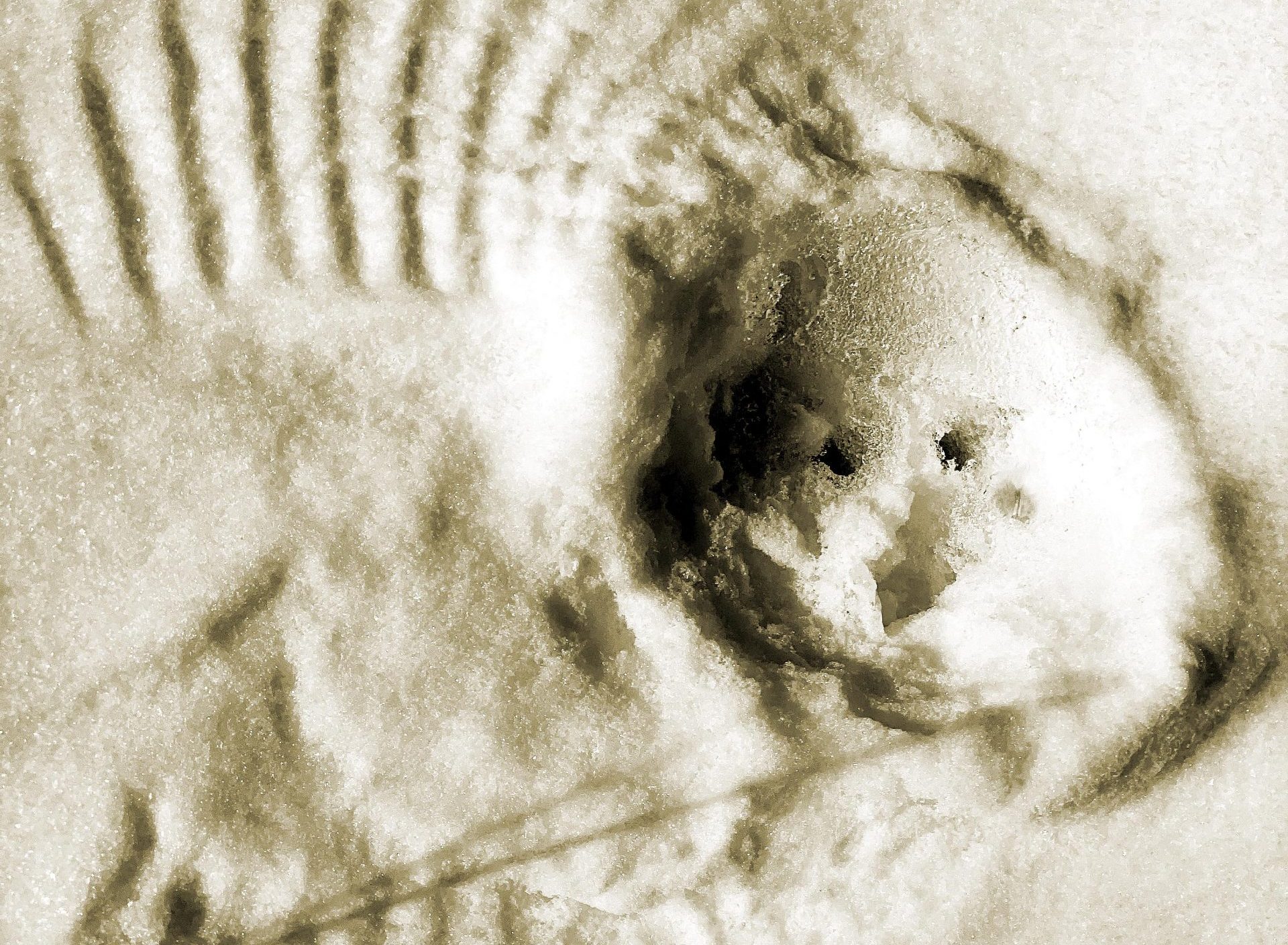

From photographs I sent to expert tracker Linda Spielman, she was able to tell me wonderful little stories about what animals on our farm were doing last winter. At the top of our hill, a mouse bounded across deep snow, its hind feet sinking into holes made by its front feet. “Lots of animals do this kind of thing in deep snow because it takes less energy than making new holes with the hind feet,” she said. “Imagine walking behind someone in a foot of snow — you would probably step in the holes made by the person you were following.”

In the field where we gallop our horses, a vole made a tunnel on top of a hard layer of snow and under a lighter layer.

In the woods, a squirrel paused on all four feet, then stood up on its hind legs — scared perhaps, or maybe just looking around. It made a small leap and took off again.

Three tiny, forward-pointing toes and one backward-pointing toe was the clue that a delicate track was a little bird. “Small, hopping birds are often mistaken for mice,” she said.

“We were all trackers once,” Spielman writes in her book, “A Field Guide to Tracking Mammals in the Northeast,” referring to our hunter-gatherer ancestors who tracked for food to survive. But when that became unnecessary, tracking was almost a lost art. Now, thanks to field biologists, conservationists, wildlife officials, ecologists and amateur naturalists, tracking has been resurrected. “It is more acceptable now as a reasonable tool to study wildlife,” she said. Tracking schools can be found throughout the country; Spielman teaches tracking classes in Ithaca, N.Y.

A crow or a turkey. Had the trail width been measured, the identification would have been more definite.

I am not an expert tracker, only an amateur observer, but I like tracking because I want to know which creatures live among us — those we can see, and those we cannot. So, last winter, after a lovely snowfall, I went into the forest, camera in hand, to see what tracks I could discover.

Finding tracks was the easy part. Identifying them was not. Coyote tracks can look like dogs, rabbits like bobcats, mink like squirrels. Spielman admitted that tracking is “a lifetime journey,” but said, “don’t be intimidated and say you don’t know enough. Just get out there and look!”

Still, do not do as I did. Be prepared.

I should have taken with me six basic items: a camera; a notebook; a pencil; a 6” clear ruler; a tracking guide; and measuring tape — because measuring, I learned, is key to proper identification. While in the woods, I should have measured the length and width of the footprint itself, and the distance between footprints, because that reveals the speed and gait at which the animal was moving. Spielman recognizes five basic gaits: walk, trot, bound, lope and gallop. Most important, I should have measured the width of the overall track pattern. If I’m confused, say, whether a track is a chipmunk or a red squirrel, I need to know that chipmunk trails are usually 2 1/8”–3 1/8” wide, whereas red squirrels are 3”–4 1/2”.

A zig-zag is the most common track pattern, Spielman said, which indicates a walking gait — right, then left, then right, similar to the way we walk, and includes such animals as cats, dogs, deer and bear (all of which trot, lope and gallop as well). A straight-line pattern, on the other hand, indicates animals that bound, such as rabbits and squirrels. Their tracks show all four feet together, then a space, then four more feet.

Trackers say it’s often easier to get a good measurement of a track pattern than the track itself because footprints look different depending on the ground being walked upon: snow, mud, sand or clay — called substrate in tracker lingo. “Substrate adds an extra complication to tracking,” Spielman said. Other complications include animals that spread their toes in different ways, aging tracks that get rained on or covered in new snow, and some animals have more hair on their feet in winter so their tracks look different. I was fooled initially by snow that had fallen from trees and made marks on the ground. “Snow plops!” Spielman said immediately, giving them a name, “another thing that can cause confusion.”

Trackers look for other signs as well: scat, urine, nibbled shrubs, felled trees, dens and middens — or refuse heaps — powerful clues to which animals are about. Chewed acorns might indicate the presence of gray squirrels, deer droppings that white-tailed deer have been near, and gnawing at the base of a tree the work of a porcupine.

Know which animals live in your region, Spielman advised, and use all your senses. Listen for the bark of a mother fox alerting her young. Know that red fox urine smells like skunk. Touch the tooth grooves on trees felled by beavers and feel the iciness of a winter deer bed. Spielman even encourages her students to taste sap in late winter and early spring when squirrels make the sap run by biting the branches of sugar maples.

But tracking is more than simply a good way to know where animals roam; it’s a visual language that tells us when animals are scared, who’s chasing them and what they eat. That’s where the stories come in. “All of a sudden there’s a little scene going on, a clue to what animal it is, but also to what happened,” Spielman explained. I was charmed by this, because I love stories. Radio collars, she said, can tell us an animal’s location, but tracking tells us “what they did all day, every day, for days and days, and gives you all kinds of other information.”

Paul Rezendes, tracker and wildlife photographer, writes in his book, Tracking and the Art of Seeing: “Tracking an animal makes us sensitive to it — a bond is formed, an intimacy develops. We begin to realize that what is happening to the animals and to the planet is actually happening to us. We are all one.”

If we are all one, might tracking encourage us to better protect the wildlife in our own backyards, to help conserve their habitats? Spielman thinks so. “If people don’t know the animals that live around them, they won’t care.” Tracking, she said, makes the lives of animals real — as real as our neighbors next door. “And if we don’t care about them, we human beings can do real damage.”

And what if future trackers tracked us? What sort of footprint will we leave that might be discovered; what might our tracks suggest? What “little story” will our movements tell about our short time on this fragile planet we call Earth?

“The Peace of Wild Things”

By Wendell Berry

“When despair for the world grows in me

and I wake in the night at the least sound

in fear of what my life and my children’s lives might be,

I go and lie down where the wood drake

rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.

I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.”

From The Selected Poems of Wendell Berry (Counterpoint, 1999)