What Happened to Youngstown?

It’s a hell of a thing to know your birth coincides with a line of demarcation in your hometown. On one side is prosperity. On the other, ruin.

I was born in Youngstown in 1977. At the time, it was an industrial city, known for its steel production and a variety of attendant industries. The city was fraying at the edges, but mills and factories dotted the landscape, making everything from office furniture to small cars for General Motors. It wasn’t an easy living, but it could be a good one.

And then it all stopped.

Three weeks after I was born, on a day they still call Black Monday 45 years later, Youngstown Sheet and Tube announced one of its mills would close — at the end of the week. The company, founded in 1900 to keep steel mill operations local and at one point the largest corporation in Ohio, had been swallowed up in the era of conglomeration in the late 1960s. Out-of-town ownership flew into the nearby Pittsburgh airport and held a board meeting, and just like that, 5,000 people would be out of work.

And it got worse. Sheet and Tube went the way of all flesh, ultimately ceasing all operations in Youngstown. The U.S. Steel mill closed as well. An entire way of life was vanishing — and taking a lot with it. It was estimated that a total of 50,000 jobs were gone by the early 1980s. There wasn’t a ripple effect — it was like a tidal wave.

Like a strange sense of déjà vu, I occasionally caught glimpses of what used to be while growing up in Youngstown. Even decades later, there are signs of prosperity, if from generations ago: big, beautiful homes on what used to be the city’s Millionaire’s Row on the North Side, a jewel of an urban park, a symphony.

But those are bright spots among the ruins. A city that once had one of the highest rates of home ownership in the country is now looking for money for demolitions. The city’s lost a third of its population just in my lifetime — and far more from its mid-century peak.

Forty-five years on from Black Monday, the area hasn’t recovered. And I’m not sure it will.

The Mahoning Valley — typically thought of as Mahoning, Trumbull and Columbiana counties in Ohio — seemed foreordained to make steel. Deposits of iron ore and coal made the area an iron producer in the 1800s. And when Sheet and Tube was formed in 1900, it was originally named the Youngstown Iron Sheet and Tube company. The open-hearth blast furnaces were enormous — and labor-intensive. Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe and around the Mediterranean flocked to the city, and by 1920, it was estimated, four out of five residents were immigrants or first-generation Americans.

The influx of immigrants led to a certain clannishness. Every ethnic group had its own church, funeral home and in many instances, social club. Even generations later, my friends held graduation parties at the Polish Krakusy Hall or the Croatian Home. (Mine was at the Lebanese church hall.) The schisms went deeper than that. There were clubs not just for Italians, but for Italians from the same regions. (I once dated a girl whose grandmother was an old East Side Italian. She quizzed me on who I was related to, where they went to church and what street they lived on.) Family relationships could be severed by marrying outside of one’s ethnicity.

In the first two decades of the 20th century, the city tripled in size, and always seemed to punch above its weight — thanks in no small part to Youngstown Sheet and Tube. Albert Kahn designed the Stambaugh Building, which housed the steel company’s headquarters for half a century. Joseph Butler endowed an American art museum with a collection that’s the envy of the world. (Seemingly every child in school takes a field trip there. I figured every city had a museum like that.) Youngstown was served by four major trunk line railroads, and its theaters and music venues attracted every major act of the day — likely a testament as much to its location, halfway between Cleveland and Pittsburgh, as to its prominence.

The Warner brothers got their start in Youngstown, and after they were on the path to success, opened an opulent movie theater on West Federal Street, prompting Mayor Joseph Heffernan to crow at its dedication, “Everything in New York is coming to Youngstown but Grant’s Tomb and the aquarium.”

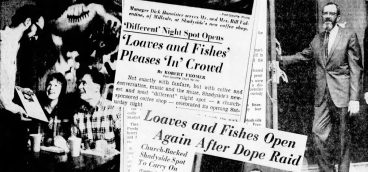

And that included organized crime.

The mills and factories gave a lot of people disposable income for the first time in their lives — and there were a lot of people who were determined to provide services to take that income.

Every city in the era had someplace where people could gamble illegally, and Youngstown was no exception. Just outside the city limits was the Jungle Inn, with bingo, booze, table games and entertainment. (Occasionally, a young crooner from Steubenville would come up, sing a few songs and deal some blackjack. He went on to become Dean Martin.)

In 1939, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reporter Ray Sprigle, fresh off winning a Pulitzer Prize for detailing Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black’s Ku Klux Klan ties, turned his attention to organized crime in the Youngstown area, and was stunned.

“Your Eastern Ohio racket correspondent, having been around quite considerably in 30 years of newspaperwork, thought he had seen pretty nearly everything and knew most of the answers,” Sprigle wrote in the final installment of a five-part series in August 1939. “He now begs leave to report that he hadn’t seen nothing.”

Sprigle found not just a wide-open town, but elected officials who were indifferent (at best) to illegal activity like gambling casinos and sports books. It was a match made in hell: A place with enough money to engage in all the vices — and people who were willing, even eager, to make it all happen.

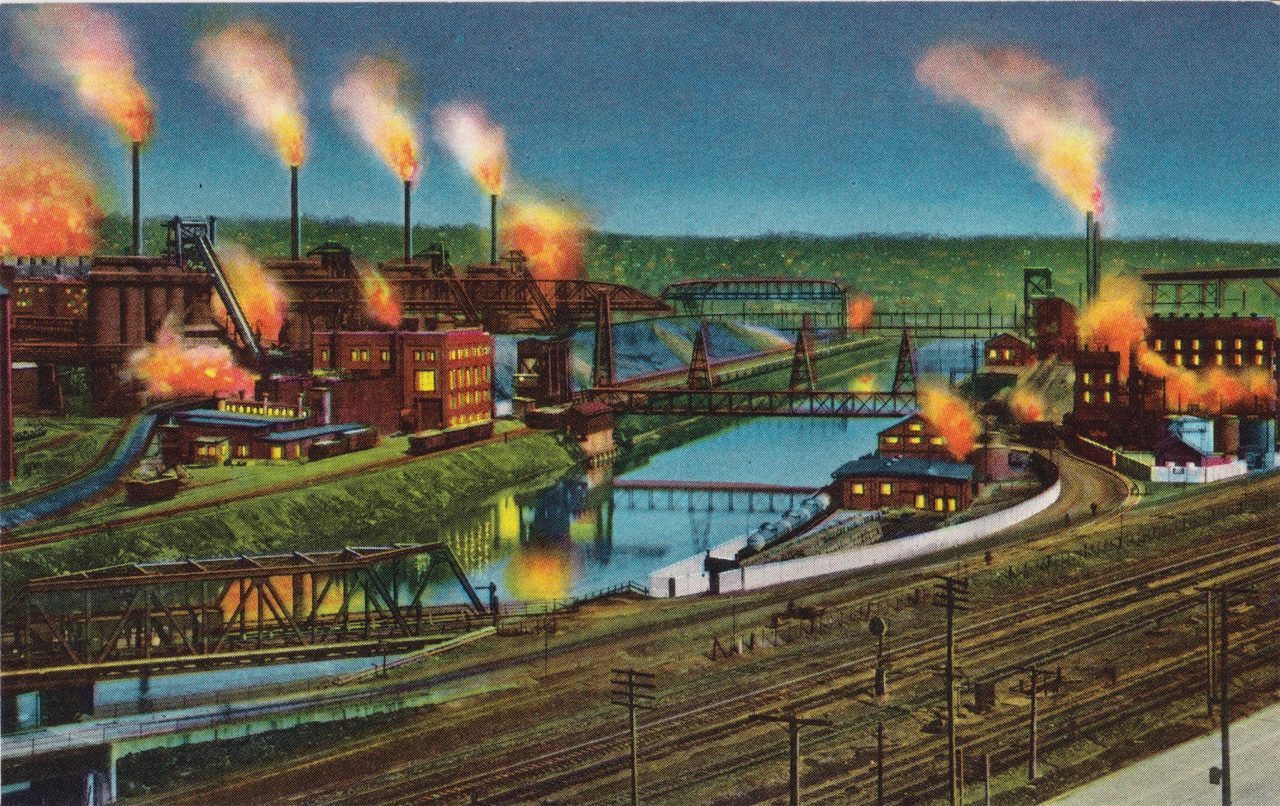

The mills sprawled along the Mahoning River from the Pennsylvania state line up past Warren, referred to as the Ruhr Valley of the United States. They ran around the clock, with skies gray with soot during the day and glowing orange at night. You could set your watch to the whistles that blew to signal lunch or shift change. Generations of men worked in and around the mills. The idea that the mills would close down was like suggesting the moon would fall out of the sky.

But if the Mahoning Valley was foreordained to make steel, the mills’ decline was just as inevitable. Open hearth furnaces had been supplanted by basic oxygen or electric furnaces. Steel mills in Germany and Japan — built after those countries had been reduced to rubble in World War II — were making better and more cost-effective steel, even taking into account transportation costs.

In 1969, Lykes — a New Orleans-based shipping company one-sixth the size of Sheet and Tube — bought the company. Justice Department investigators didn’t want the sale to go through, saying the steel company wouldn’t survive, but they were overruled by U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell (later notorious for his role in the Watergate scandal). Lykes continued to buy other companies — and did NOT update the open hearths in Youngstown until finally, overextended and out of credit, they closed down a mill. And then another. And then merged with another conglomerate, LTV. Republic Steel went bankrupt. Its mill closed too. U.S. Steel was rebranding and shuttered its mill too.

The effects were broadly felt for years. The two department stores downtown closed (although that probably had as much to do with suburban malls and department store consolidations as it did with Youngstown’s economic fortunes). The local amusement park, which had tied its fortunes to ethnic and company picnics, also closed, its demise hastened by a fire just before what turned out to be its final opening day. As a first grader, I watched from the playground at Kirkmere Elementary as the smoke from the fire climbed over the treetops of Mill Creek Park. And people started leaving. I was supposed to go to West, but schools closed due to declining enrollment; boundaries were redrawn, and that’s how I ended up at Kirkmere. There were kids in elementary school or on my youth baseball teams who would just vanish. Their families found another opportunity — or went looking for another one — somewhere else.

Eventually, the mills came down too. There were efforts to assemble an employee-owned company, but the Carter administration wouldn’t guarantee the hundreds of millions in loans needed to upgrade the facilities. The mills were torn down, the land slated for brownfield cleanup — but not before they had become backdrops for political ads about working people being left behind.

Ronald Reagan said it was “Morning in America,” but it was the proverbial dark night of the soul in the Mahoning Valley.

There’s always been a pervasive cynicism in Youngstown. There were jokes that the politicians and the police were “the best that money could buy.” A 1963 Saturday Evening Post story called Youngstown “Crimetown USA” and ended with the kicker that barbers in town would cut your hair for $2. For $3, they’d start your car for you.

Because all the mills closed seemingly at once, some type of magic bullet was sought, a big-ticket factory that once again would employ thousands. Plans for a blimp factory on the east side never materialized. Neither did one to make commuter aircraft at the Youngstown-Warren Regional Airport. The region tried to lure GM’s new Saturn division (as a second-grader, I was part of the letter-writing campaign). A Pentagon payroll center appeared to be awarded, but a change in presidential administrations (from George H.W. Bush to Bill Clinton) led to that project being scuttled as well. A total of 406 Avantis — the car company that lived on after Studebaker went under — were built in Youngstown, but the big plans never materialized.

Then in the early 2000s, people saw fracking as the key to the area’s revitalization. Someone else got the money. All Youngstown got was earthquakes. The cynicism that was around during the good days hardened into something darker.

The mills closed. The mob didn’t. Remember the line from “The Godfather,” where Clemenza says a war’s needed every 10 years or so to get out all the bad blood? That’s what the Mahoning Valley was like: Good for a mob war every 15-20 years or so — and one played out just as the mills were closing. The Mahoning County Sheriff at the time was a former Pitt quarterback named Jim Traficant. The son of a truck driver (albeit with master’s degrees), Traficant ran a community action agency and coached high school football before catching the political bug. He ran for county sheriff and parlayed that — after defending himself and beating a federal bribery charge — into a seat in Congress, the only new Democratic representative following the 1984 election.

Traficant was the closest thing the Mahoning Valley had at the time to a friend in high places. He looked like a buffoon with his wild hair and, uh, interesting fashion choices, but always had something interesting to say. He once quoted “Indian Reservation” by the Raiders on the House floor, and came up with a unique solution to the 1994 MLB strike. “Negotiators should be locked in a room with no windows and air conditioning and should be fed baked beans, fried cheese, hard-boiled eggs and chocolate kisses,” he was quoted as saying by the Associated Press.

“In eight hours,” Traficant paused, his voice rising for effect, “they’ll be pleading, ‘Play Ball!’ ”

But it wasn’t all grandstanding. He talked about the poverty that had beset the Mahoning Valley, the dangers of open borders and the influence of China in foreign and business policy. He made a quixotic run for president in 1988, but had he come along 20 years later, when chip-on-the-shoulder populism was coin of the realm and elected officials could build followings on social media, he might have gotten elected.

As it was, we got a different tough talker with unique hair. Donald Trump’s election in 2016, two years after Traficant’s death in a tractor accident, resulted in a lot of contemplation — particularly due to the reaction of the Mahoning Valley. Once a Democratic stronghold, the area tilted for Trump, who won Trumbull and Columbiana counties. (A strong showing by Hillary Clinton in the city of Youngstown kept Trump from becoming the first Republican since Richard Nixon in 1972 to carry Mahoning County.)

Meanwhile, things got bleaker. The General Motors plant in Lordstown — the last vestige of the industrial way of life in the area — was “unallocated” in 2018, and the last car rolled off the line the following year. An electric truck company came in making big promises. As of summer 2022, no trucks have been delivered. But residents of the Mahoning Valley must have liked what they saw from Trump. In 2020, he carried the entire three-county region: Trumbull, Columbiana and Mahoning counties. They’d been looking for someone to Make the Mahoning Valley Great Again for YEARS.

In June of 1995, I walked across the stage to collect my high school diploma at Stambaugh Auditorium, a Greek-revival facility built by and named for one of the city’s captains of industry. At the time, there were still four public high schools in Youngstown, and the commencements were one right after the other. (Now they’re down to two, and the Youngstown City Schools was just released from state control, less because of its own achievements and more because people started to realize just how onerous the bill allowing for state takeovers turned out to be.)

I was heading off to college to study journalism. I didn’t think I’d come back to work at the Vindicator. (The Youngstown paper, shuttered in 2019. The Tribune-Chronicle in Warren puts out an edition under the Vindicator banner, but it’s not quite the same.)

Some friends went away to college, but a lot of the people I went to school with who continued their education did so at Youngstown State. A few are still trying to fight the good fight in the Mahoning Valley, but a lot of us have scattered to the four winds. I ended up in the Pittsburgh area initially. I’m now in the Cleveland area, in no small part because I missed roads that met at right angles and being able to buy beer at a gas station.

I’m about as close to Youngstown as I want to be right now. I’m also as far from it as I want to be.

Vince Guerrieri is a journalist and author in the Cleveland area. He spent his salad days in Washington County as a reporter for the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review.