The Strategy of China’s Xi

From the beginning of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms in the early 1980s right up through the first decade of the twenty-first century, China’s socialist-capitalist hybrid society worked remarkably well.

Previously in this series: On Agency Part V, Deng’s Accidental Revolution

The Chinese economy grew rapidly and the Chinese people – post Tiananmen Square, anyway – accepted the CCP as their unchallenged masters. “Give us all power,” said the CCP, “and we will make you rich.” For a desperately poor society, it was an offer they couldn’t refuse.

That’s not to say that storm clouds weren’t gathering. But those clouds went largely unnoticed by the West, whose leaders were mired in the deeply mistaken belief that China would gradually evolve into a more democratic society.

But if we analyze what was happening in China through the lens of individual versus collective agency – that is, by resort to Chinese history – we can easily see where Western observers went wrong.

While the West had its head in the sand, serious issues were accumulating in China, most of them having to do with the conflict between the two traditional Chinese forms of human agency. The most serious of the problems were these:

Chinese economic growth inevitably was going to slow, despite individual agency policies, simply because large economies can’t grow as rapidly as small ones. China would grow rich in the aggregate but would remain poor on a per capita basis. This outcome would eventually undermine the give-us-power-and-we’ll-make-you-rich justification for the CCP’s monopoly on governance.

Because the rule of law is very weak in a one-Party Communist system, corruption in the CCP would gradually grow to gargantuan proportions – to levels utterly unknown in the democratic West.

Collective agency strategies that would artificially pump up economic growth – i.e., debt-fueled growth policies in the housing sector – would have to be employed but would ultimately prove to be unsustainable.

A collectivist Party – the CCP – that could murder its own citizens in Tiananmen Square wouldn’t hesitate to commit genocide against non-Han groups (especially the Uyghurs) suspected of disloyalty.

Because of the power of individual agency operating in the economic sphere, it was inevitable that private companies and private individuals would eventually amass clout that would threaten the CCP.

China’s collective agency response to problems like overpopulation and COVID would lead to short-term gains but threaten long-term disasters.

Although the West has blamed President Xi for adopting policies that are inhumane, anti-democratic, stridently nationalist, and anti-free markets, the reality is that Xi assumed power precisely at the moment the aforementioned problems came home to roost.

Thus, the question isn’t whether or not China had to take drastic action to face up to its problems; the question is whether Xi would focus on collective agency solutions or individual agency solutions. Clearly, Chinese history offered both options and, clearly, Xi has chosen to adopt collective agency approaches to deal with every dark cloud looming over China:

As China’s economic growth rate collapsed – the IMF is predicting 4.8% growth for 2022 – Xi could have doubled down on Deng Xiaoping’s free markets (individual agency) policies. Instead, Xi has clamped down on China’s most successful companies and industry sectors, favoring state-related enterprises (i.e., collective agency) that are far less productive and which are growing at far slower rates.

Rather than subjecting CCP members to the rule of law – the individual agency approach – Xi chose to attack his enemies in the Party under the guise of smashing corruption. Certainly the Party figures who were toppled were corrupt – but so was everyone else in the Party.

To deal with slowing growth, Xi chose to encourage ever-more borrowing by companies in the housing sector (think Evergrande). This certainly gave the economy a short-term bump, but debt-fueled growth always hits the wall.

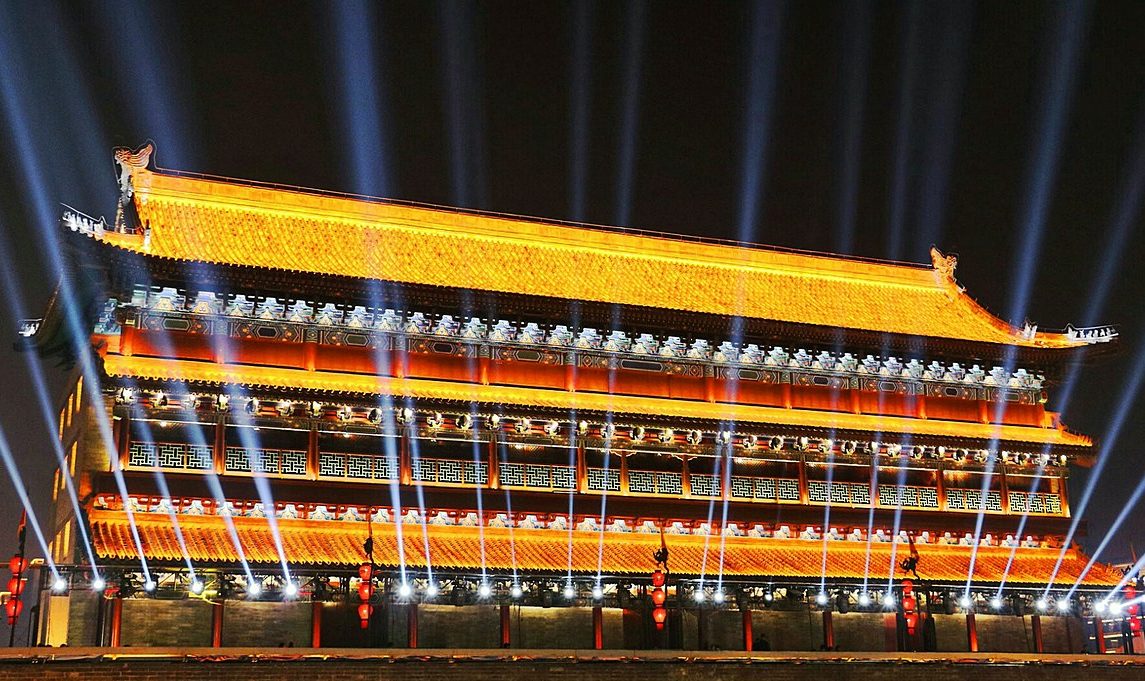

Using excuses like terrorism and supposed threats to the primacy of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi has asserted collectivist, Orwellian control over the Chinese people.

As companies like Alibaba and Tencent grew large and powerful, Xi didn’t recommend stronger antitrust laws (the individual agency approach being followed in the West), he simply cracked down on them arbitrarily. Rather than rely on Deng’s individual agency policies, Xi turned to state-owned enterprises that were much easier to control.

As noted, China’s approach to overpopulation and COVID has been collectivist and arbitrary – albeit impressively effective in the short term.

President Xi is the fifth paramount leader in the dynasty launched by Mao Zedong but, along with Mao and Deng Xiaoping, one of the three most consequential. Mao founded the dynasty after defeating the Nationalists in a great civil war, but then ran the country into the ground. Deng introduced individual agency into China’s economy, with momentous results. But as China’s challenges multiplied it fell to Xi to find solutions.

As noted, Xi chose collective agency approaches to every problem facing the country, following a tradition launched more than 3,000 years earlier by the Shang Dynasty. Collectivist policies have historically appealed to Chinese emperors because they allocate all decision making to the ruler, consolidating his power, at least in the short term.

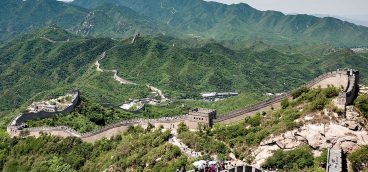

But the Shang were eventually – and rather easily – defeated by the Zhou. The Qin, another collectivist dynasty, accomplished great things but lasted only 14 years. Emperor Wu’s collectivist policies allowed him to conquer territory after territory, but those policies also made his people miserable – he repented, introduced individual agency policies, and launched China’s Golden Age.

If Chinese history is any guide, we can expect President Xi’s collectivist policies to accomplish a great deal in the short term: building up China’s military capabilities, threatening and perhaps even invading Taiwan, bullying China’s neighbors, asserting ever-greater control over China’s populace, building alliances with other authoritarian regimes (especially Russia), and so on.

We can also expect that Xi’s policies will ultimately fail: China’s economic growth, which has been powered by free market individual agency, will eventually fossilize; Xi’s aggressive approach to international relations will spawn a vast anti-China coalition; Omicron (or the next variant) will burst through China’s tyrannical lockdown system; the Chinese people, having tasted individual agency in their economy, will ultimately revolt against Xi’s collectivist policies – and powerful rivals in the CCP will engineer Xi’s downfall.

Next week we’ll return to the West and take a look at where human agency stands in contemporary America.

Next up: On Agency, Part 7