A billboard along U.S. route 22 just west of Johnstown offers up to $54,000 and “guaranteed employment” for incoming nursing students at nearby Mount Aloysius College. As the billboard signifies, higher education institutions have taken a lead role in Johnstown’s transition from steel to health care as the primary economic driver. The burgeoning health care field is an economic bright spot in a region whose history has been dominated by historic floods and, in more recent decades, the loss of manufacturing jobs. Not surprisingly, the most important issue leading into the 2022 midterm election is the economy.

“The biggest issue we hear from our chamber members is the labor shortage; they need reliable workers,” said Amy Bradley, president and CEO of the Cambria County Regional Chamber of Commerce. “There are at least 1,000 available jobs in Cambria County right now. These are good-paying, family sustaining opportunities, but the workforce is not available. This impacts everything from restaurants to manufacturers.” Johnstown’s August unemployment rate was 9.2 percent, and Cambria County’s was 8 percent. Contributing to the shrunken labor pool, she said, is population decline. Cambria County’s population fell by more than 10,000 people in the decade ending in 2020, the second-biggest total population loss — and eighth-largest percentage among Pennsylvania’s 67 counties.

“A lot of things play into this, infrastructure, regulation and taxation,” Bradley said, adding that “supply chain is also an issue right now. This is likely the result of the pandemic, but it has the potential to hurt our small businesses if they can’t get the goods they need. This could lead to more shopping online and less support for local businesses, which we don’t want. I think our community did exceptionally well through COVID. Because we are a smaller community, people really know and support small business. I had one restaurant owner tell me he sold more gift cards the first month during COVID than he did the entire previous year. We had very few businesses close permanently.”

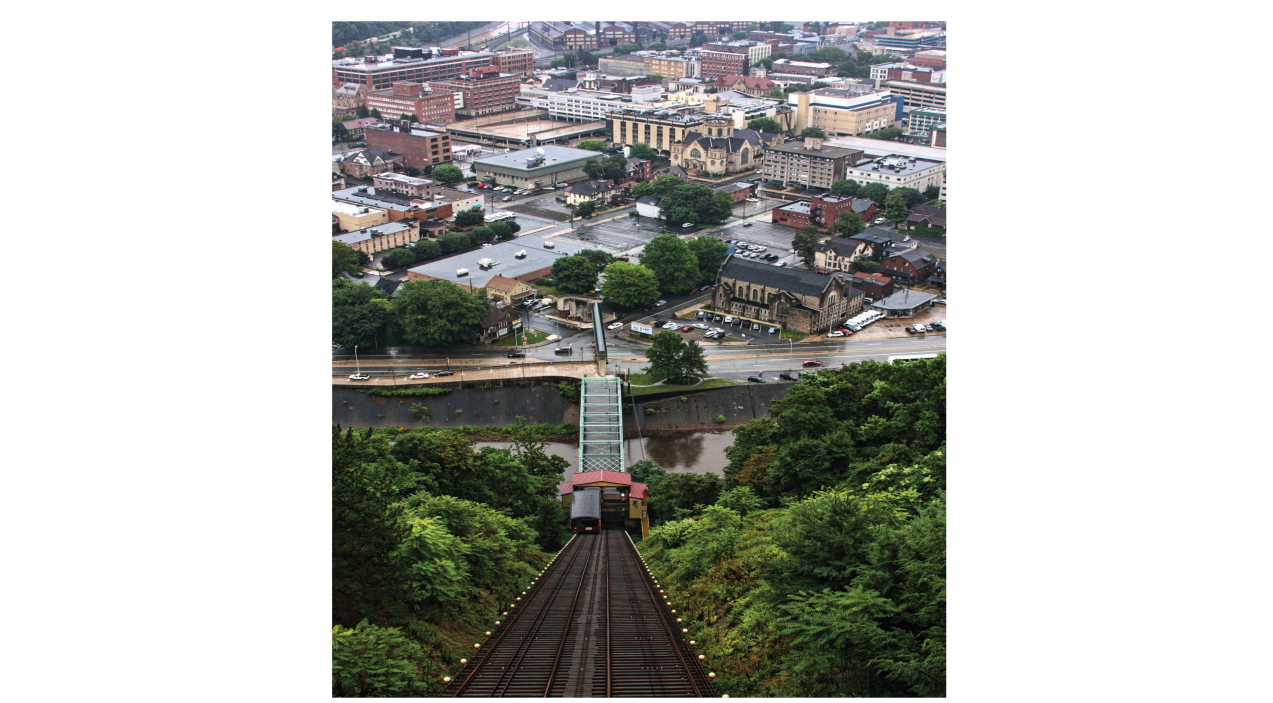

Johnstown has experienced the same kind of political split as the rest of the country regarding COVID, said Chip Minemyer, editor of the Tribune-Democrat. “The same debate is playing out here. There’s a lot of effort to educate people on the issue, but if you don’t trust science and don’t trust information, you’re not going to go there anyway.” Economic ills, he said, go hand-in-hand with the pandemic. “We have more jobs than people lining up for them — service sector, welding, nursing is a huge need area. Another economic driver is economic tourism — events like motorcycle rallies, hiking, biking, whitewater, music festivals.” Judging by the letters to the editor, he said that abortion is the second-biggest issue after the economy in the region, which he called a “big-time” 2nd Amendment area.

Dominating the front page and local news section during a sample week in October were Cambria County courting a $3 billion U.S. Steel mini-mill, an upcoming employment fair, city plans for spending of the federal government’s American Rescue Plan funding, the reconstruction of an area mine-drainage site, and extension of a local walking trail. Following closely were health care-related stories, with a heavy emphasis on COVID, and crime stories also were heavily featured.

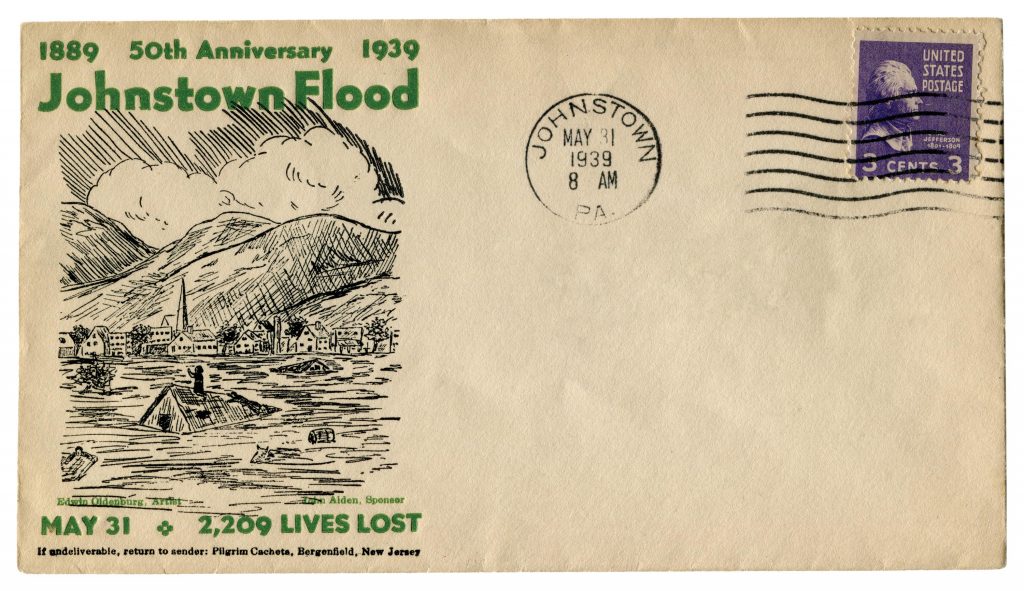

An informal survey of 45 city residents for this article asked them to rank 12 issues. The survey was distributed in three areas. One site took in two downtown Clinton Street restaurants — Coney Island, and the Flood City Café, a popular, funky eatery and coffee shop with a small sound stage. The second was the streets adjacent to the downtown’s Central Park, featuring a fountain, statues of a Civil War soldier and the city’s founder, and a plaque commemorating the park’s role in the historic Johnstown flood of 1889. Ringing the rectangular one-block green space are a couple of mobile phone stores, a sandwich shop, a hobby outlet, tobacco store, a bank, a pizzeria, a small motel and abandoned storefronts. The third survey site was the food court at Johnstown’s biggest mall, the suburban two-tier Galleria, anchored by Boscov and J. C. Penney, where food traffic was sparse on a Monday morning and only one of the six available restaurant slots was leased — by a Chinese restaurant. The mall was sold to its creditor, U.S. Bank National Association, at a sheriff’s sale this year. The economy led the survey responses by far, listed as the top priority, followed by education and health care, climate change, race relations and abortion.

In the last two presidential elections, Johnstown was overwhelmingly Republican, with former President Trump winning 66.5 percent in 2016 and 68 percent in 2020. But the GOP trend is relatively recent; in the 1996, 2000 and 2008 races, the Democratic presidential candidate carried Cambria County.

“People think the Republicans are more aligned to their values,” editor Minemyer said in explaining the shift. “Economics, abortion, and job creation are issues that drive a lot of people here. Also, there’s been a shift to an anti-government mood here.” However, he said, “The city of Johnstown is more Democratic, but that’s not the case once you get outside of the community.”

The famous quip by Democratic election analyst James Carville that “Pennsylvania is Philadelphia and Pittsburgh with Alabama in between,” is a bit simplistic, said Pennsylvania State University political science associate professor Christopher Beem, who directs the McCourtney Instititute for Democracy, which analyzes national political moods, “There is some truth to it. I can’t explain it (the Republican voting shift) specifically. All I can do is think about it in terms of some common features, along with other counties throughout the nation that had similar turnout and voting totals. Cambria County is largely white, rural, Christian, and its economic growth over the last two or three decades has been slow and non-existent. There is a large national cohort that voted for Obama in 2008 and 2012 and then voted for Trump in 2016. From the policies that Obama ran on, compared to Trump’s campaign, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. What you hear from most people is that when they evaluated Obama in terms of his candidacy they felt a sense of hope, and when they evaluated it in 2016 they felt a sense of disappointment. The features in their lives they wanted to change did not change, or did not change sufficiently. Whether that is true, that was the perception. They didn’t want more of the same. It’s really hard to prove that, but from the surveys I’ve seen, that is the most common explanation and the one that I find the most persuasive.”

Cambria County is primarily Christian (nearly 70 percent of county residents claim some form of Christian church membership). Only a fifth of the county’s residents aged 25 and older have college bachelor’s degrees or higher levels of education, according to most recent census figures. The county is older than the rest of the state, with a median age of 46.3 years compared to a state median of 40.8. The percentage of county residents living at the poverty level as of 2019 was 15.3, compared to 12 percent in the state. The median cost of a detached home in the county that same year was $143,006 compared to $255,931 in the rest of the state. The 2019 estimated median household income was $49,076, compared to a state median of $63,463. Caucasians comprise 96 percent of the county’s population, compared with African Americans at 3.2 percent and Hispanics at 1.8 percent. Midterm elections, Beem said, are “almost always an assessment of the presidential administration, especially when it’s new. More often than not, that first midterm for an incoming administration, the reaction of voters is negative. The Party that is not controlling the White House does better in the midterms. So you’ll have people judging Biden’s administration by COVID, the state of the economy, and the Afghanistan withdrawal. The only reason that might not happen this time is because the suburbs around Philadelphia went for Biden, and if Trump makes himself a factor, that could bring continued support for the Democrats. Because of the Supreme Court abortion ruling regarding Texas, that could push women toward the Democrat party.”

Beem said much of the midterm voting will depend on the outcome of President Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure legislation and the reconciliation bill — and voter response to those will depend on how soon people start feeling any results of the legislation.

“You can’t get Americans to agree on the color of the sky, but you can get them to agree on their dissatisfaction with politics. It’s difficult to see, or even theorize about, a way out of this mess. I think most people are frustrated and impatient with politics, and there also is a level of anger with a large segment of the population that is manifested not in just angry words but in literal violence — for example, what you see going on in school board meetings, which suddenly have become the focus for not just shouting but literal violence. People see this and believe that things are not running well. We have established a kind of partisan status quo where we distrust or dislike the other side, to a degree I haven’t seen in my lifetime. I think it’s not about politics; it’s about culture.”