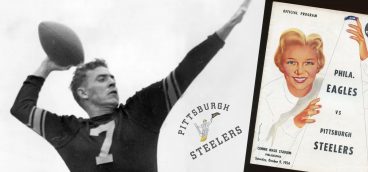

Remembering a Steelers Season to Forget. CARD-PITT

The fresh snow and twinkling lights had Pittsburghers in the holiday spirit, but alone in his hotel room John Grigas had spiraled into a dark place.

He had played 19 games in his professional football career. His teams had lost all 19. With his soul suffering and his body battered, could he drag himself through one last game?

As Grigas contemplated what awaited him the next day — the fearsome Chicago Bears defense pile driving his body into the rock-hard Forbes Field turf, the frozen chunks of mud slashing him like razor wire — the answer became clear.

While his roommate Don Currivan slept, Grigas tiptoed to the desk and picked up a pen.

Dear Don,

Did not want to wake you up.

Funny thing, everything seems so mixed up. I’m gone now. Can’t change my plans. Take care of my bags.

Best of luck,

Johnny

With that, Grigas walked away from the wreckage of the most disastrous season in National Football League history.

During World War II, Uncle Sam plucked the Pittsburgh Steelers clean, as player after player entered the service. The NFL rescued them in 1943 by approving a temporary merger with the equally depleted Philadelphia Eagles. A season later, it was time to repay the favor. The re-emergence of the Cleveland Rams after a year’s absence, combined with the addition of the Boston Yanks, left the NFL with 11 clubs and the league couldn’t create a suitable schedule with an odd number of teams. After some arm-twisting, Steelers owners Art Rooney and Bert Bell agreed to a one-year merger with the winless Chicago Cardinals. The new team’s grungy nickname — Card-Pitt — proved apropos.

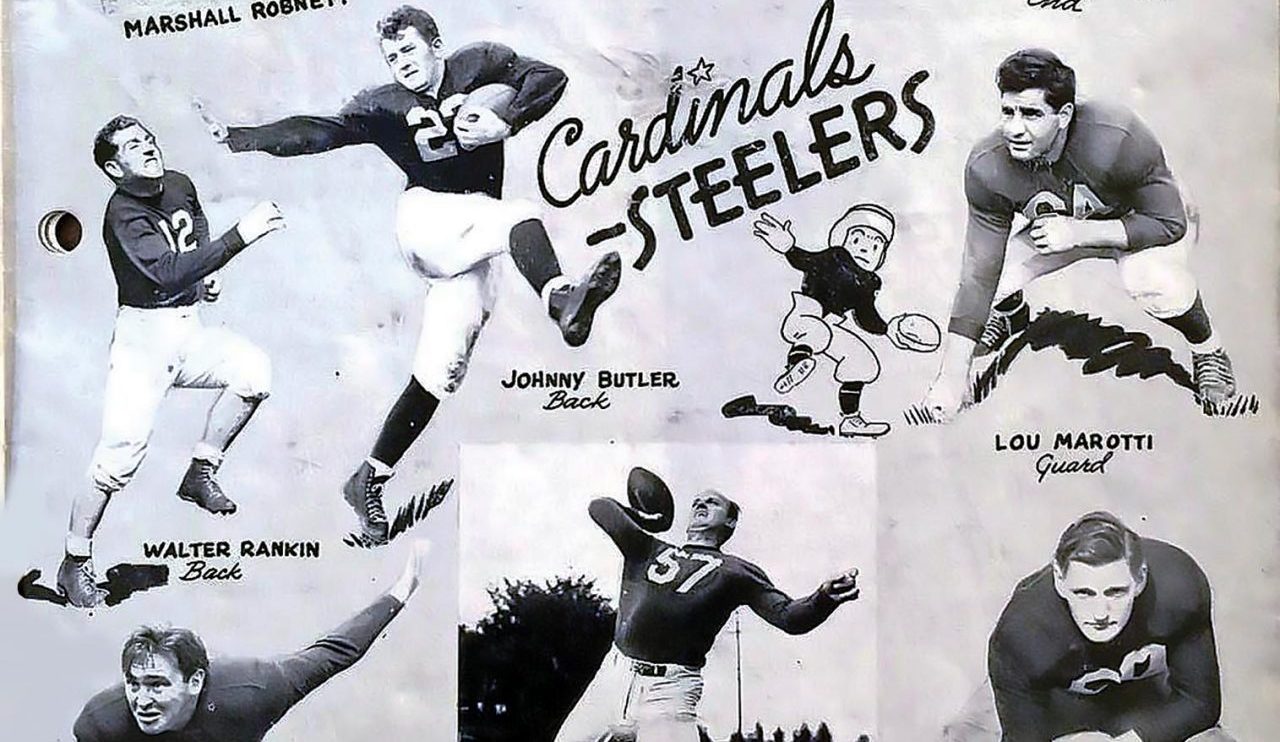

Grigas, a second-year fullback, was a durable and dangerous runner. His teammates were mostly a danger to themselves. Card-Pitt’s best end, Tony Bova, was blind in one eye and partly blind in the other. The top quarterback entering training camp was creaky 37-year-old Walt Masters, who had aged four years in the last eight months. (“No one believed me last year when I said I was 33, so I might as well tell the truth,” he reasoned.) End Clint Wager played five games for the Cardinals in 1943; while practicing his punting that season he missed the ball, slammed his knee into his forehead, and fractured his own skull.

“Something unique was bobbing up every day,” said assistant coach Buddy Parker. “Looking back, it’s hard to believe they actually happened.”

“One week we were supposed to play at Comiskey Park [in Chicago],” recalled co-head coach Phil Handler. “Eddie Rucinski, who lived out in Indiana somewhere, never showed for practice. About 10 minutes before game time, he rushed into the dressing room. Said he was home painting the barn all week. We had to play him; didn’t have anyone else.”

On the first day of full practice drills, six players toppled over with heat stroke. After Card-Pitt lost its first preseason game in a mud pit in Philadelphia, 22-0, Bell told reporters it was the worst team he had ever seen.

Card-Pitt nearly defied that prediction in the regular season opener. They rallied from behind to seize a 28-23 lead over Cleveland and then intercepted a Rams pass at their own 1-yard line with just four minutes remaining. But instead of running down the clock and risking a fumble, Card-Pitt chose to punt — on a first down, no less. The punt fluttered nine yards. Three plays later, Cleveland passed for the winning score.

Then Card-Pitt lost its starting quarterback to the Army, leaving only one option to run the offense against mighty Green Bay — Johnny McCarthy, a diminutive, prematurely gray 28-year-old rookie from St. Francis College. McCarthy threw four interceptions in a 34-7 loss, but to him just surviving felt like a victory. “I thought I’d be so scared I wouldn’t be able to throw the ball.”

After a drubbing by the Bears the following week, Handler and his fellow coach Walt Kiesling fined three players, including Grigas, $200 for “indifferent play.” Their teammates responded by refusing to practice. Kiesling shouted that whoever didn’t want to play should leave. A few did. Eventually, Rooney stepped in, soothed all hurt feelings, and quietly rescinded two of the fines — all in time for Card-Pitt to get blasted by the New York Giants, 23-0.

Week 5 brought more mayhem, as Washington knocked McCarthy out of the game with a dirty hit. Card-Pitt retaliated with a cheap shot of its own, and the subsequent pushing and shoving rapidly escalated into a small riot. Kiesling and Handler were right in the middle of it, police swarmed the field, and even Rooney, a former amateur boxer, charged in, fists up, before coming to his senses.

Without McCarthy there were no quarterbacks to be found; the only option was playground football. The game plan for the rest of the season was to snap the ball to Grigas and let him run, throw, or do whatever he wanted. That didn’t work, either; Card-Pitt lost its next four games resoundingly.

At least Rooney maintained his sense of humor. Handler told the owner about a letter he received from a high school coach who wanted a copy of the team’s playbook. “That guy must be nuts,” Rooney deadpanned. “We haven’t won a game.”

Before the season finale, Grigas confessed to a couple of teammates he had quitting on his mind, even though he had an outside chance at the NFL rushing title. On Saturday night, Currivan went to a hockey game but Grigas declined; he needed space to think.

“They had just about worked me to death all year.” Grigas remembered. “It had been building up a long time and that night I decided I’d had it.” By morning, he was gone. The Bears crushed Card-Pitt, 49-7, a fitting end to a futile experiment.

Card-Pitt was outscored 328-108 and led only twice all season. They established a pair of sad NFL records, throwing 41 interceptions and punting for an average of just 32.7 yards.

When Grigas stepped off his train back home in Boston that Sunday, it was all behind him. Rooney held no grudge. “He had a hard time in those days,” said Grigas decades later. “They were hard for all of us, but he forgave me and never has forgotten me.”

The Steelers struggled plenty in those early years, but according to Rooney, nothing matched Card-Pitt. “Merging those teams didn’t make us twice as good. They made us twice as bad!”