Fitting into West Virginia

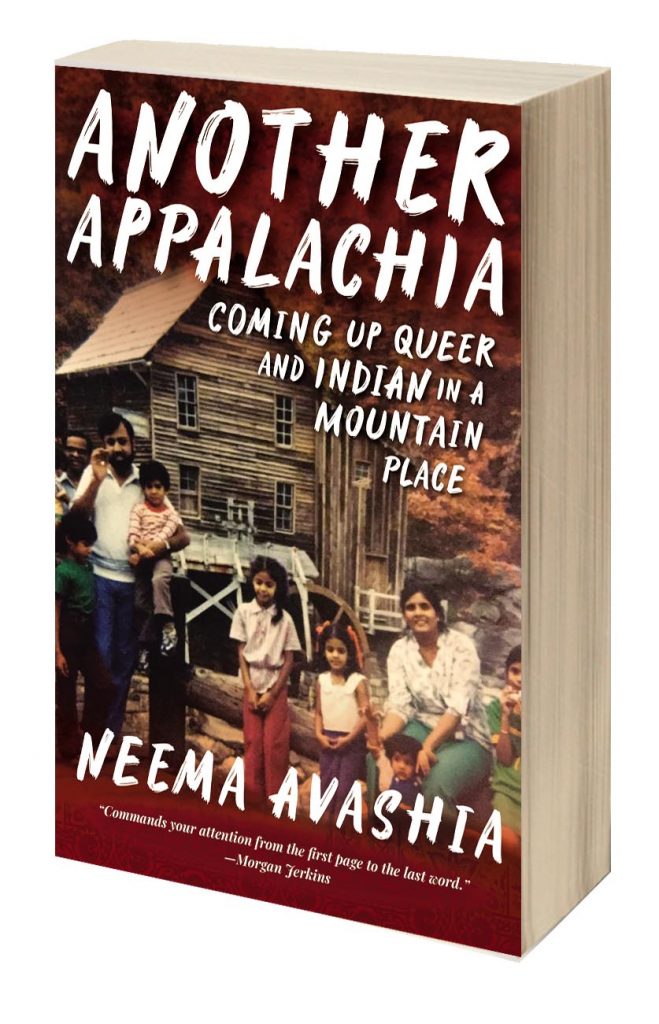

In writing, place can be both problematic and inspirational. Take James Joyce’s troubled relationship with his Irish homeland. Ireland’s Catholic, nationalist values were reasons enough for him to never enter his native land after 1912. And though he died in 1941, his masterpieces remain redolent of Dublin. In her captivating debut memoir, Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place, Carnegie Mellon University grad and Boston-based educator Neema Avashia takes a more straightforward approach, using pathos and pointed analysis to capture the complexities of West Virginia.

As the child of an Indian physician who immigrated to the U.S. for medical school in 1969 and later took a job with Union Carbide in Charleston, Avashia brings a fresh perspective on being an “other” in a state with a miniscule minority population — a state looked down upon even by her one-time classmates in Pittsburgh, “the Paris of Appalachia.”

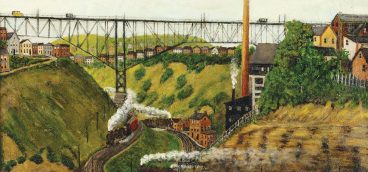

In the stunning opening chapter, “Directions to a Vanishing Place,” Avashia sets the stage by blending Google Maps and nostalgia as she takes readers to a place “right after the Pink Pony strip club, … the exit for Cross Lanes, West Virginia. The exit for the place you call home.” Winding through this small town, with its requisite pawn shops, bars, and a car wash, she pauses at her childhood address, close to the Union Carbide plant where her father worked. From there, memories emerge: “Pass the double hill between the Carneys’ and Mundays’ houses, where you whiled away hours of your childhood. Summers, you played King of the Mountain, wrestling with your friends for positioning at the top of the hill. Winters, you crashed your sled into the icy creek with glee, then hauled it back up the hill and rushed back down again.” Moments such as these linger, like Annie Dillard’s classic, An American Childhood. The sparkle of homecoming fades when she notices “the ramshackle conditions of abandoned mining communities in the southern part of the state creep into the very street where you once lived.”

If there’s a rhetorical question to be answered in Another Appalachia, it’s “Why West Virginia?” The answer: “At the time, Indian immigrants did not have extensive options. They most often found work in the places where privileged Americans would not venture, in the midst of either urban or rural poverty.” Through his talents as a physician, Avashia’s father adapts and assimilates by being generous with the neighbors, giving flu shots and physicals at no charge. The family has “all the needed ingredients for the American dream … thanks, in no small part, to Union Carbide.” That this will be the same company whose plant in Bhopal, India, leaked 30 tons of methyl isocyanate, killing upwards of 15,000 and blinding and burning thousands more, comes to feel like cruel irony. Avashia writes of the corporate clean-up, “Carbide needed to send a crisis team to India. They wanted my Indian father to be part of their otherwise white team. …What would he have lost if he said no?” In the end, the company paid less than $800 for each of the Bhopal families who filed claims.

Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place

by Neema Avishia

West Virginia University Press ($19.99)

This leads her to a friendship with her coach, Carl Bradford, who implores her to shoot like Wilt Chamberlain once shot free throws: granny-style. When she scores her first bucket, readers will want to cheer, as the 9-year-old Neema “grows so dizzy with this overwhelming sense of belonging that I fail to register the final score.” While the moment is short-lived, it’s obvious that Bradford remains an important influence in her upbringing. There’s also the case of another local she’ll remain friendly with, Mr. B and his wife. As an adult, she’ll question how to feel about the kindly Mr. B who begins embracing anti-immigrant views online. Throughout the book, Avashia shares her experiences with the casual but stinging racism as she tries to wrap her head around the online behavior of people who’ve shown her kindness over the years.

In many ways, Avashia’s Another Appalachia is a pointed response to J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. Avashia embraces the cohesive power of food and how native flavors such as ramps and okra become a part of her vegetarian palate. It’s not enough, though, as she’ll be told to “go back where you came from” — though in defiance, she’ll “flaunt my West Virginia roots, to wear T-shirts emblazoned with images of West Virginia and the lyrics to ‘Country Roads.’” She adds that while remaining quiet in the face of overt racism, she wants “to assert my Americanness. My West-Virginia-ness. To pull out the birth certificate detailing my birth at Thomas Hospital in Charleston, West Virginia, in the heart of the Kanawha Valley. That muddy river valley, those green mountains, those smoking chemical stacks — they are where I come from.” It’s in the historical and cultural grasp of her home state that she proves she’s bona fide.

In an interview with CNN, Avashia bridges the gap on how she views her identity, saying, “The notion of chosen family is at the core of being queer. It’s at the core of being Appalachian. And it’s at the core of being an immigrant in this country. In all three cases, the way that people are building relationships is not confined by biology. It’s a product of proximity. It’s a product of necessity.” That Another Appalachia fills that space with nuance and hard-won pride is unsurprising as Avashia speaks from both head and heart.