Airmen Behind Enemy Lines

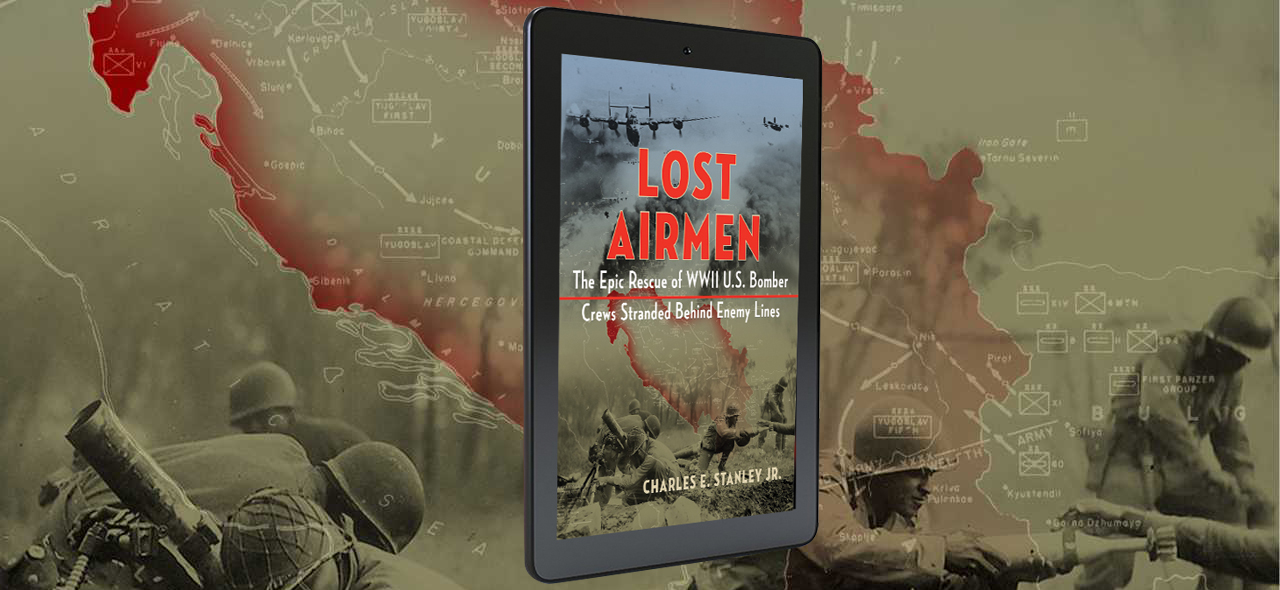

As illustrated by the stories of eight Pittsburgh-area natives, downed airmen who bailed out over Yugoslavia during World War II experienced vastly different fates, from daring rescues to drowning and execution. Lost Airmen: The Epic Rescue of WWII Bomber Crews Stranded Behind Enemy Lines tells their stories and many others.

Pilot Charles “Scotty” Stewart ordered his crew to bail out over Yugoslavia after flak punctured his B-24’s fuel tanks and it became clear that he would not be able to return to his base in Italy. His crewmen parachuted safely but Stewart landed among a group of boulders high on a mountainside and broke his right leg in three places. Unable to move, he would have died of shock, hunger, and exposure if a small lad had not discovered him and summoned some villagers to help.

Eventually, a partisan doctor set Stewart’s leg in a crude cast and he was reunited with his crew. They became stranded in Sanski Most, a small town in modern Bosnia, until British agents arrived and arranged for C-47 transport planes to carry them back to Italy.

After surgery and months of recovery, Stewart was assigned to participate in a public relations campaign to sell war bonds. While on tour, he befriended a bright, young naval lieutenant who was also recovering from war wounds, John Fitzgerald Kennedy. After the war, Stewart graduated from Harvard, settled in Pittsburgh, and became a prominent business executive

Two weeks after Stewart bailed out, pilot Charles Stanley of East Brady and his ball turret gunner, Sgt. Peter Homol of Pittsburgh, also were forced to abandon their B-24 over Yugoslavia.

Rescued by Marshal Tito’s partisans, Stanley and his crewmates were ushered to the same town that harbored Stewart and his crew. Eventually, 84 airmen gathered there, far too many for the war-torn town to support. A month later, three transports arrived to evacuate them, but they did not have enough room to carry everyone. Stanley, Homol and 16 others stayed behind. One was Lt. Lewis Baker, a co-pilot from Pittsburgh. Soon, the hard-pressed partisans ordered the airmen to hike 120 miles across the Dinaric Alps during the worst winter of the century. Two of their partisan escorts froze to death before the party reached safety.

Stanley carried his parachute the whole way. Once he returned Stateside, his fiancé used the material to make her wedding dress.

Radio operator Raymond Klapp of Irwin bailed out of his B-17 when it stalled and went into a steep dive after a bombing raid against Munich. Sgt. Klapp was captured and became interned in Stalag Luft IV, one of Germany’s cruelest POW camps.

Two months after Klapp’s capture, the Germans decided to evacuate the camp in the face of Russian advances from the east. For weeks, 6,000 Allied POWs endured a murderous retreat now called the Black March. Hundreds died of starvation. Other were killed by civilians who resented their bombing raids.

Eventually, the German column broke down. Word spread that Hitler had ordered all prisoners to be killed. Luckily, Klapp’s guards abandoned him. The starving POWs were finally discovered by British troops in late April 1945.

Blue-eyed, blond-haired, Gosta “Gus” Sundquist was born in Sweden but grew up in McKeesport. A draftsman by trade, he could have avoided military service because his profession was deemed vital to the war effort. Instead, he volunteered for the Army Air Forces and became a B-24 ball turret gunner.

On Dec. 15, 1944, mechanical problems forced Sundquist’s crew to bail out before they could reach their target in Austria. Unfortunately, clouds obscured their view of the ground and a recent heavy rainfall had swollen a swamp that lay below. Sundquist and two crewmates landed in the frigid waters and drowned. Navigator Frank Dick was captured by the Germans and executed after he refused to answer their questions. The rest of the crew escaped with the help of partisans and returned to Italy after a series of hair-raising adventures.

Some of the downed airmen were helped by the partisans’ bitter rivals for the control of post-war Yugoslavia, the Chetniks led by General Draža Mihailović. In fact, Thomas Koballa, a B-24 flight engineer from Charleroi, and Lawrence Zellman, a P-38 pilot from Ernest, PA, met with Mihailović several times while they were stranded in the Chetniks’ camp.

By this time, the Chetniks had all but lost their civil war with the partisans. Yet, even as Mihailović prepared for his last stand against Tito’s men, he took time to arrange for the transfer of the Americans to the partisans through a neutral party. Thus, Koballa and Zellman were among the last outsiders to see Mihailović before his capture and execution at the hands of the partisans.