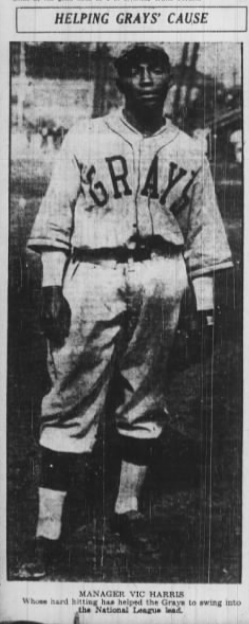

The Homestead Gray’s Vic Harris: Baseball’s Winningest Manager

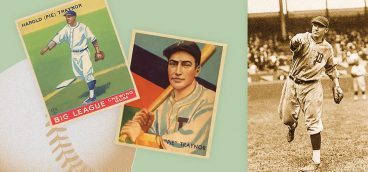

When ranking baseball managers, historians often use the number of times a manager led teams to a victory in the World Series as a yardstick for measuring their greatness. By that measurement, Major League baseball’s greatest managers are the New York Yankees Joe McCarthy and Casey Stengel. Each led Yankee teams to seven World Series championships.

Philadelphia As Connie Mack, with five World Series titles, is third among baseball’s winningest managers, while the Dodgers Walter Alston and the Yankees Joe Torre, each won four. Under Alston, the Dodgers won their first and only World Series in Brooklyn before moving to Los Angeles, where Alston led them to three more titles. Torre led the Yankees to four World Series titles, but only after he was fired by the St. Louis Cardinals.

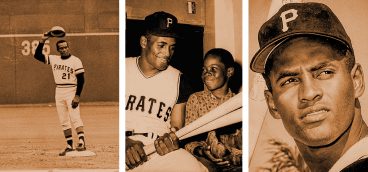

All of these managers are in the Baseball Hall of Fame, but the doors at Cooperstown remained closed to Vic Harris, who led the Homestead Grays to eight Negro League championships. This year, Harris, the winningest manager in baseball history, was passed over once again by the Early Baseball Committee (prior to 1950), while Bud Fowler, who played in the 19th century and is generally regarded as the first African-American to play professional baseball, and Buck O’Neill, best known as the Negro League’s greatest spokesman, were voted into the Hall of Fame.

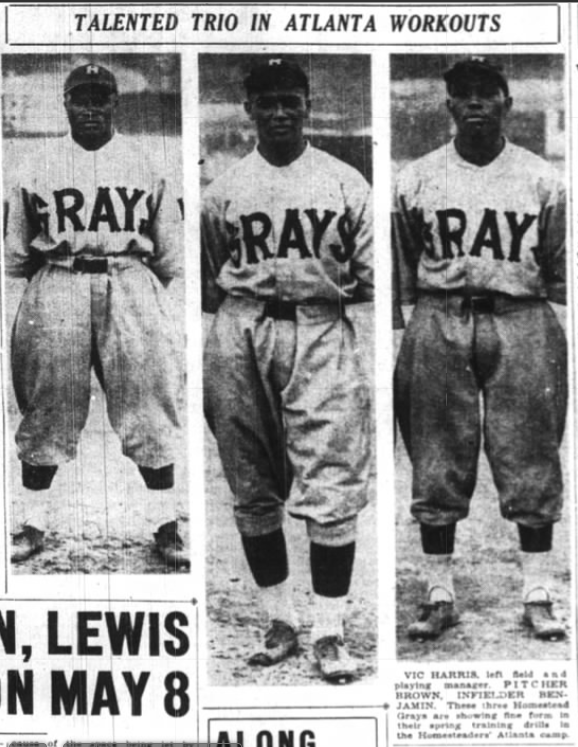

While Bud Fowler and Buck O’Neil deserve to be in the Baseball Hall of Fame because of their importance to baseball history, neither had the credentials of Vic Harris. As a ballplayer, Harris was often described as the Negro League’s Ty Cobb. His long-time teammate Buck Leonard said that when Harris slid into second base “he just undressed the opposition infielder.” Dick Seay, who played second base for the cross-town rival Pittsburgh Crawfords, claimed that Harris “would cut you in a minute. Cut you and laugh.”

While Harris was as vicious and dangerous on the base paths as Cobb, he, like Cobb, was an outstanding hitter. In a decades-long career, he had a life-time batting average over .300 and usually led off for the Grays or hit second in front of Buck Leonard and Josh Gibson, regarded by many as the Negro League’s Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth. He was selected for the Negro League East-West All-Star game seven times and finished his career as a player in the top ten in almost every Negro League offensive category.

Born in Pensacola, Florida on June 10, 1905, Elander Victor Harris was “nine or ten years old,” when his family moved to Pittsburgh as part of the great migration from the South of African-Americans seeking better jobs and a better life. After attending Schenley High School from 1919 to 1922, Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey, who was aware of Harris’ talent, offered him a contract right out of high school. Harris, at first, declined the offer, but after two years of drifting from team to team, he finally agreed to join the Grays for the 1925 season.

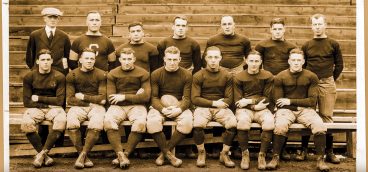

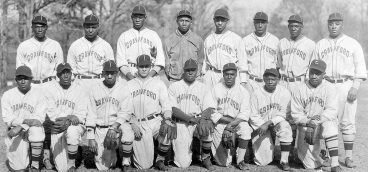

When Harris signed with Posey in 1925, it marked the beginning of a relationship that, with the exception of 1934 when Harris jumped the Grays to play for the cross-town rival Pittsburgh Crawfords and 1944-1945 when he took a job working in a defense plant, would last until 1948. In those years, Harris would play with and eventually manage several of the greatest players in Negro League history and manage the Grays to eight Negro League championships

When Posey brought Harris back to the Grays for the 1935 season after he had jumped to the Pittsburgh Crawfords, he named him the Grays’ player-manager. Harris remembered, “He had been managing the team until then. He was fiery and he knew I was fiery, so he made me manager.” Posey’s decision to turn the Grays over to Harris proved to be one of the most important in Negro League history. In 1937, the Homestead Grays would begin a run of nine straight championship seasons and Harris would be the manager for seven of those championships.

Following the war, Harris returned to the Homestead Grays from his defense plant job, and, after two losing seasons, led the Grays to the pennant in 1948, one year after Jackie Robinson integrated baseball, and to a victory over the Birmingham Black Barons in what proved to be the last Negro League World Series. One of the players on the Black Barons team was a 17-year-old Willie Mays.

While Mays was destined to join many of the Negro League’s best players in the slow integration of the baseball and play his way to the Hall of Fame, Vic Harris was worried that “if they take the best of our boys, we will be but a shell of what we are today.” He recognized that baseball’s integration was “a good thing” for Negro League stars, but “then again, it might not be” for the rest of the players in Negro League baseball.

Harris proved a prophet when organized Negro League baseball collapsed and the Homestead Grays were reduced to barnstorming. He left the Grays and sign on as a coach in 1949 with the Baltimore Elite Giants. After managing the Elite Giants in 1950, he retired from baseball and moved to California with his family. He settled in Castaic, a small community located in northwest Los Angeles county, where he became the head custodian of its Union Schools. After a long bout with cancer, he died on February 23, 1978 at the age of 72. His death came just three years after Frank Robinson became the first African-American to manage in the Major Leagus when he became the player-manager for the Cleveland Indians.

There are 37 Negro League players and five executives in the Baseball Hall of Fame, including Cum Posey, who is honored as a “player, manager, and owner,” but there is no Negro League manager. Wouldn’t it be a great thing for baseball, as it recognizes Negro League baseball’s team and individual records, to open the doors of the Baseball Hall of Fame to Vic Harris, who managed Hall of Famers Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, and Cool Papa Bell on his way to becoming the winningest manager in baseball history.

(The primary source for this article was Charlie Fouche’s entry on Vic Harris in Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays and the 1948 Negro League World Series).