Renewing the Promise of Pittsburgh

Editor’s note: Historian David McCullough delivered the following words on a Pittsburgh riverboat in a speech to a select group of local leaders at the launch of the Riverlife Task Force. We are publishing this essay for the first time with permission of The Heinz Endowments on the occasion of the launch of a new campaign of renewal: Pittsburgh Tomorrow. His words are as potent now as then in pointing the way to a new Pittsburgh.

I think this is an opportunity such as no city in the country has. and i think that it isn’t just a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity — it’s a once-in-a-century opportunity. What can be done can change the character of the city, can improve the good life in the city for at least another century. And that’s a terrific, thrilling chance. It’s also a tremendous responsibility.

My comments here tonight are given from the heart, and they’re given with some request for your indulgence, because I don’t want to be presumptuous. Here I am, someone coming to Pittsburgh who doesn’t live here and who’s out of touch with the politics and the business realities, who seems to sound as though he has the answers. I don’t have the answers, but I think I have some answers from the lessons of history.

I can tell you that I have been interested in the history of this city since I was a little boy. I have collected material all my life. I have a considerable library of Pittsburgh’s past and Pittsburgh’s impact on American history, which is a very important point, it seems to me. I love this city. I have never not come back year after year, two or three times a year. I have two brothers and their families here. And, until not very long ago, my mother and father were living here in the house I grew up in. My family on both sides — my mother’s side and my father’s side — has been here in this place since before the Revolutionary War. I feel a very strong sense of roots.

One of the best histories ever written by an American, The History of the United States of America During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson by Henry Adams, chose as its starting point … Pittsburgh. One could choose a lot of starting points when writing a history of America during the administration of Thomas Jefferson — that’s roughly 1800–1810 — but he chose Pittsburgh because he was saying to his readers that there were in effect at that time two Americas — an eastern seaboard America and the great inland empire beyond the Alleghenies. And only at one point were they joined, were they connected. And it was here — at this Gateway, as it’s come to be known.

And of course, one of the most magnificent examples, a metaphor for the joining of the two empires, east and central midwestern America and beyond, was the Lewis & Clark Expedition, which was launched by President Jefferson. And as I hope you all know, Lewis & Clark’s boat was built here. In 1803, that boat pushed off for the unknown.

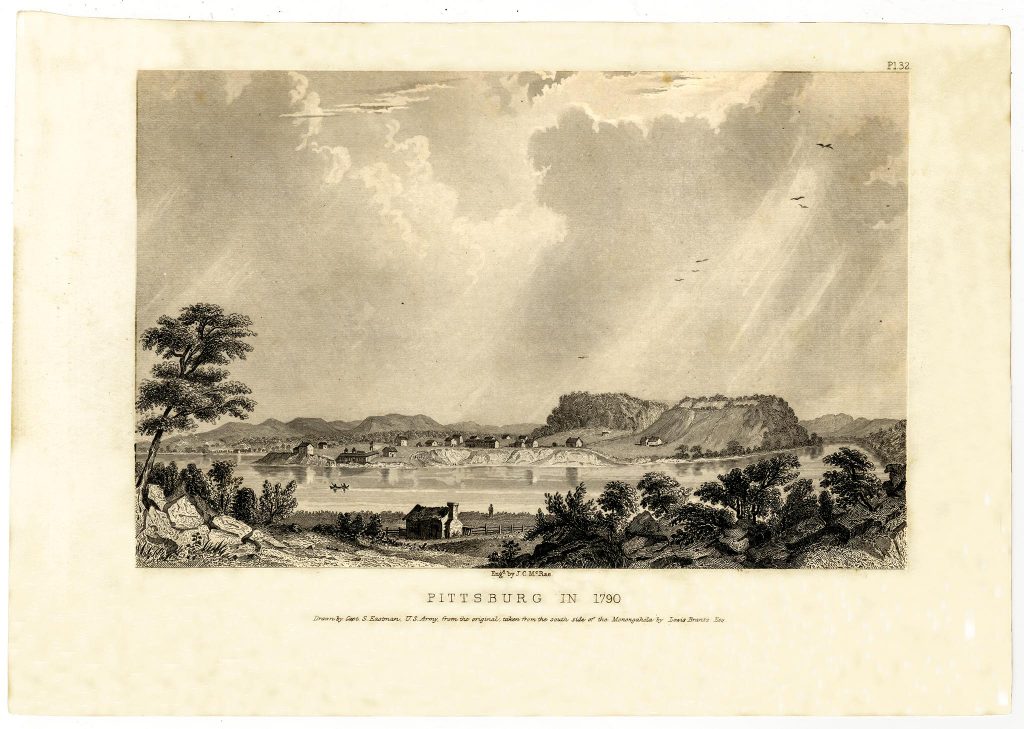

Lewis Brant’s artist sketch of Pittsburgh in 1790. courtesy of the Detre Library & Archives at the Heinz History Center

I think it’s a very good sign that we are at another historic moment in the history of this city and in the history of our country. What we do here has immense importance to the country as an example. If we believe, as I think most of us do, that our cities are the vital organ of civilization, that you have to have vibrant, productive, exciting cities in order to have a vibrant, productive, exciting civilization, then this city, with all that it has to its advantage, and now with this terrific opportunity, can be a showcase to the whole country, and bring back a sense of confidence in the city and a commitment to the ideals of the city that can bring a great lift to people everywhere.

One of the earliest sketches of Pittsburgh was done by an artist named Lewis Brant in 1790, about which he wrote, “The view from this spot is in truth the most beautiful view I ever saw.” Not very long after, another observer said, “The scenery around Pittsburgh is very beautiful, and when viewed from some points presents the most interesting associations of nature and art imaginable. The view from Castleman’s Hill [now known as Squirrel Hill] is not surpassed by any in the country. Earth, air, rock, wood, water, town, and sky break upon the vision in forms most picturesque and delightful.” Then you move forward into the 19th century, and people like Charles Dickens come here, and, in his “American Notes” published in 1844, he says, “It certainly has a great quantity of smoke hanging about it, but it was also very beautifully situated.”

And we saw tonight how very beautifully situated it is. And how relatively unspoiled it is, considering all that happened here. When we went under those bridges, and the voice of the mayor was echoing under those bridges, well, think of the echoing of all the voices that have been in these valleys, and all that’s happened in these valleys. To a large extent, they are still as beautiful as they ever were. And almost no city in the country has anything like the treasure of that spectacular setting — possibly San Francisco one might say. But people I meet that know I’m from Pittsburgh come to me and say, “You know, I was in Pittsburgh three weeks ago, and it’s so beautiful!” When you come out of the tunnel — and we all have had this experience, but imagine what it’s like if you’ve never seen it — and there it is. You don’t have to create that. There it is — all these bridges. We don’t have to redo any of that. They’re here. They are the assets of the setting.

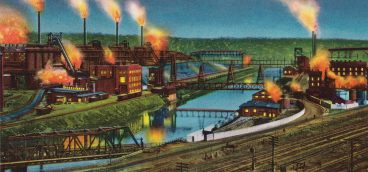

One of the richest portraits of all in the old days is a book that was published in 1826 called Pittsburgh in the Year 1826 by a man named Jones. He describes all the mills that were up and down the rivers on the two sides, where we’ve just been. This was before the real burst came in the 19th century. He describes the famous Pittsburgh Glass Works, which was the first of its kind in this “western country,” as it was called, and the Rolling Mills, the Sligo Nail Factory, the Sligo Rolling Mills, the Bridgeport Glass Works, the Albany Glassworks, the Williamsport Glassworks, the Eagle Steam Saw Mill, Boyle Irwin Salt Works. And then up the Allegheny — the Allegheny Foundry, the Allegheny Steam Mill, the Allegheny Steam Saw Mill, an immense shipping business — 70 steamboats a year arriving at the port of Pittsburgh.

And look at the old engravings. There’s a wonderful one by a German artist named Willman, which was done about 1850. I’m sure that many of you have seen this one, but if you really look at it, you’ll see the Monongahela wharf, which stretched all the way from the Point up to where the Smithfield Street Bridge is. That huge sloping bank of cobblestone was spectacular; people could walk down that slope to the very water’s edge. Hundreds of people would come out all the time; not just the people who were working on unloading the ships, but people who would just come down because it was interesting. Now say what we will about the old mills — the horrors of the mills, and the dirt of the mills, and the vile poisoning of the water — these valleys were full of life and activities and sounds and a sense of importance — of big work being done. We have to think hard about bringing life back to the valleys. The mills were monumental in scale; they were a great presence. And anybody growing up here, and I know so many of you did, felt that you were somewhere important, particularly if you were a kid during the Second World War. What was happening here was exciting, and you weren’t just anywhere. Pittsburgh was different.

I suggest to all of you that we must keep that sense of identity. We must not try to do something that is just a repetition of what’s been done other places and would wind up looking like every place else, as so much of America is turning out to be. We have to have a sense of what was here in the past, not to replicate it, but to replicate the spirit that was here — of vitality, of the sense of being in a great and important place, where things were happening, things were changing, things were growing and influencing the country.

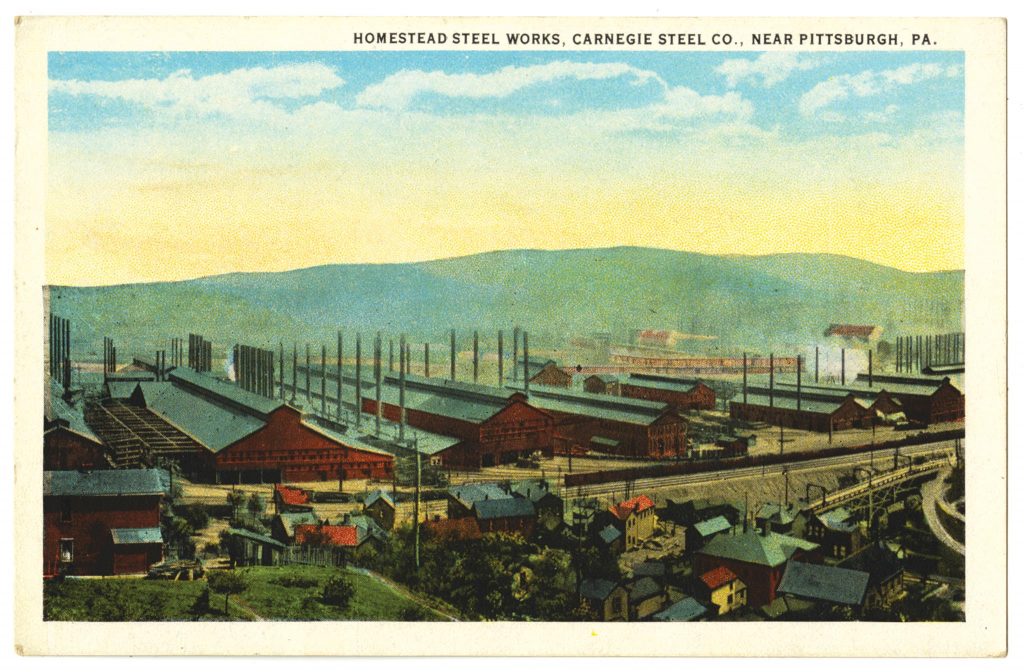

Now the big burst, as I’m sure many of you know, came in the 1870s with the advent of the Bessimer Process. All of a sudden everything changed here. Immense mills were built — the Edgar Thomson Works and the Homestead Mills — the scale of which surpassed anything that had ever happened. Not just anything that had ever happened in Pittsburgh, but anything that had ever happened anywhere. And in came the rivers of people, human beings from every part of the world and country. They weren’t just coming from Europe; they were coming up from the South and in from the American farmlands to work in these mills. Of course, the work was horribly dangerous. They were ground up. Do you know, that to work in a Pittsburgh steel mill in the 19th century was statistically more dangerous than going to war? In one year in the Carnegie Mills, more than twice the number of people who were killed building the Brooklyn Bridge, one of the most dangerous structures ever attempted up until then, were killed than in all 14 years it took to build the Brooklyn Bridge. It was dangerous; it was grim; it was unbelievably hard — 12 hours days, six days a week, for $12 a week.

But it would be a mistake to imagine that there was no pride in that. Herbert Spencer came here, the English philosopher and great proponent of the “Survival of the Fittest.” They took him out to see this wondrous creation. The old stories about darkness at noon and everything smothered in gray and fumes and grime is all truer than we know, and he looked down and he was just aghast because he thought that his philosophy had given rise to all this buccaneering. And he said, “One month in Pittsburgh would justify suicide.” James Parton, the eastern writer, came and called it “Hell with the lid off.” He was the first one to say that, and people here thought that was great! You bet it’s hell, and we’re giving them hell — we’re raising hell. And I survived that hell. I went into that mill and I came out and I built this.

This city was not just making steel, we were building thousands of miles of railroad tracks. We were building bridges everywhere, all over the country, and battleships. The possibilities of America, the reaches of America, the power of America — all were changed by what happened here. The history of this country took as dramatic a turning point in those years after the Civil War and before World War I as in any time in history. There was the advent of all the inventions that came along then, many of which happened here. And, of course, it wasn’t just steel — it’s a great over-simplification to just talk about the steel business. Most people who lived in Pittsburgh were neither steelworkers nor the barons who owned the mills. They were doing other things — they were teachers, and doctors, they were working in shops, working in all kinds of activities — and building a city that had a strong cultural life, a strong cultural identity, and great pride.

This city was hit time and time again by disasters — fires, disease, floods, strikes — all of which the city recovered from. In the fire of 1845, roughly one third of the whole city burned down. But the city that was built after the fire was a vast improvement on the city before the fire. The city survived the immense build-up of production and the “all stops out” pollution of air and water during World War II. After the war was a grim, beat up, some felt doomed city. “Decrepitude” was the word people used. And what did the city do? With David Lawrence and R. K. Mellon, people set to work to clean up the city long before the environmental movement. Pioneering a whole transformation of a city that you all knew about but that the whole country was affected by — exactly as the country will be affected by what’s done here next.

The demise of the steel industry or the decline of the steel industry was as hard a blow as this city could have been hit by, and it’s come back. It’s working. It’s moving. The recent New York Times article talked about a new spirit in Pittsburgh, and that’s wonderful. I thought it was a terrific article, but I’m not sure it’s a new spirit. In fact, I’d really like to suggest that it’s an old spirit — an old spirit that’s very strong in this community. And there’s the pride that goes along with work and the way Pittsburgh people judge other people by the work that they do. He’s a good guy. Yeah, I know him — he’s a good worker. This is very much a Pittsburgh characteristic. And those people who came into these valleys, who changed the industrial strength of America, who transformed the whole way we live in this country and in this century, are part of our history — and they’re all in this valley still. Their memories are here, and they belong to the assets of this community and this culture as much as the hills and the treasures that we benefit by — our museums, our libraries — all of that, which you cannot replace. You cannot recreate the Carnegie Library in some city overnight — can’t do it. You can’t just suddenly grow these things. They have evolved through a strong tradition in a city that matters to people who care about the good life, who believed that the ethic of service for the public good, public virtue, and improvement of life for the next generation was the way to live the good life.

Now I have a couple of suggestions to make to you in how to approach this wonderful opportunity. You can say that I’m being idealistic, and you’re right. I think that we have to be idealistic. I think that we have to approach this project in the spirit of not accepting anything that’s second best. That has to be the ideal. You have to approach this project with the spirit that idealism is your strongest card. Woodrow Wilson said, “Yes I’m an idealist — that’s how I know that I’m an American.” And I think that can be part of the spirit. Make what you do a place; make it a real place that people want to be — a great place.

And don’t make it like other places, because Pittsburgh was never, ever like other places. Make it a place where people want to bring those they love — their children, their family from some other place, some other city, to live here. Make it a place for music and sunshine and trees by the water. Make it possible to walk out of an office building down to the river, or to bring your family to a picnic by the river. Include bike trails — all the things that the mayor was talking about. But think of it on as large, as ambitious, a scale as you possibly can. And build for the long run, not for what’s going to work next week or next year — the long run. And make it in keeping with the city’s heroic past. That doesn’t just mean preserving old structures, or reminding ourselves of the history that’s here, but preserving a sense that this story that we have, that you have, belongs here and is unlike that of anything else in the country.

And you’re not going to do something insipid in Pittsburgh. You’re not going to serve weak tea to people who are used to stronger stuff. Keep it human in scale and humane in scale. I hope that you won’t think this sounds far-fetched, but keep Paris in mind. Think what the appeal of Paris is — that river. Everyone can go to the river. You have the bridges — more bridges than in Paris, and some of them are the most beautiful bridges in the country. The idea of lighting them is thrilling. And keep in mind what they haven’t done in Paris — what they haven’t built. Look at the mistakes that have been made in Pittsburgh, and learn from those mistakes. We saw one this evening — the jail. We know what was done to East Liberty. Learn from the mistakes.

Don’t use focus groups or market studies or polls — don’t think that way and don’t let anyone think that way. Choose someone of exceptional ability and talent — someone with convictions and with the courage to stand up against those who would compromise everything — as your designer. Don’t settle for anything or anyone but the best. Don’t rush into that decision — it’s the most important decision you will make. Don’t just name somebody to name somebody.

And start with a plan. You have to have a plan. As much as old Colonel George Williams had a plan when he laid out the city back here on that Point in the 1780s, you have to have a plan. You really have to know how wide each sidewalk is going to be. Don’t just build buildings and let everything fill in around them. Have a real plan.

Now, you’re not starting Pittsburgh over again, but you are reinstating attitudes and a renewal of the old spirit that have been here all along, and you’re doing it by design. When the leading citizens of Brooklyn decided they wanted to build a bridge to New York, that this was necessary for the future of Brooklyn, they didn’t just get anybody. They went to John A. Robling, the greatest suspension bridge builder in the world, who, as you know, built his first suspension bridge right here where the Smithfield Street Bridge is now. And they said to him, “Do it. Design it, and build it.” And Robling presented his plan in which he, with characteristic immodesty, said, “The finished work, when built according to my designs, will not only be the greatest bridge in the world, but the engineering marvel of the age, and a great work of art.” All of which it turned out to be. But he also emphasized that the finished work would “forever testify to the energy, enterprise and wealth of the community that built it.”

And in that spirit, I’d like to say make it a place that testifies to the energy, enterprise, and wealth of Pittsburgh, your Pittsburgh. And that it affirms your strong and affectionate belief in the future of this incomparable American city.

Alexander Pope, the great 18th-century poet, wrote a famous poem called “The Epistle to the Earl of Burlington.” He was talking about the principles of building, the principles of creating parks, spaces where architecture and nature work together. And he said that the first principle, as in everything, is good sense. And then he wrote these wonderful lines — he said, “To build, to plant, whatever you intend. To rear a column or the arch to bend. To swell the terrace or to sink the grout. In all let nature never be forgot. Consult the genius of the place in all.”

Consult the genius of this place: the man-made genius of these bridges and the genius of the place of these age-old rivers. Like the new Convention Center, which is going to repeat the catenary curve in dramatic form. Not just the catenary curve of these bridges, but the catenary curve of the original bridges designed by Robling. It is a perfect form echoing the tradition, the heritage of genius, that this city has given rise to again and again. And that to me is a very exciting piece of news — that this new structure is going to do that.

Pittsburgh doesn’t just have bridges; it has some of the greatest bridges in the world. And it began with some of the best work of some of the greatest engineers and architects ever. It doesn’t just have a symphony orchestra; it has the Pittsburgh Symphony. Keep that star of excellence yours to steer by, and make the most of this absolutely wonderful, exciting opportunity. And on you go!