Reflections on Masculinity

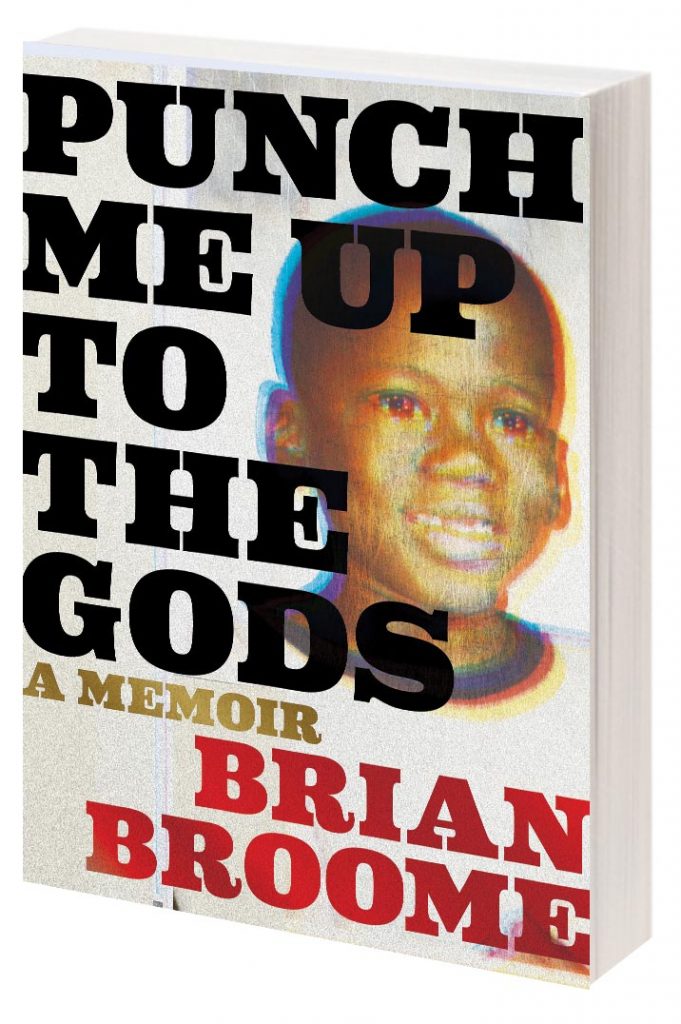

In his award-winning recent memoir, Punch Me Up to the Gods, Brian Broome lovingly describes the antechamber of the now-defunct Hills Department store in his hometown of Warren, Ohio as smelling “like the emotions of a child. Pre-adolescent bacchanalia. It was dizzying. It was a roasted peanut, soft pretzel factory wrapped inside a chocolate-covered everything. It was the aroma of popcorn; cold red Slushee; hot dog jamboree with dusty corners; and waxy yellow buildup on the floors at a time when two dollars could buy you the world. …It wasn’t just a snack bar. It was the mountaintop.”

by Brian Broome

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

($26.00)

As readers will see, these moments of simple childhood pleasures for Broome grow complicated when back-dropped with intersecting issues such as race, poverty, and a growing awareness of sexuality.

A former K. Leroy Irvis Fellow and an instructor in the writing program at the University of Pittsburgh, Broome is also a graduate of Chatham University. Using familiar settings, both in Ohio and Pittsburgh, is just one aspect that makes this debut, a New York Times Editor’s Pick and the winner of the 2021 Kirkus Prize for Nonfiction, sparkle on the page. There’s also the way he pays homage to the great James Baldwin, “visiting Saint Paul de Vence, where he lived and died before I ever knew who he was. … He was, like me, a gay man who loved his people. He loved his country too, but he recognized his country would never love him back. Baldwin spoke, knew who he was, and never allowed anyone to tell him any differently. I am not like him.”

Framed around Gwendolyn Brooks’ classic poem, “We Real Cool,” Punch Me Up to the Gods is ultimately a reflection on masculinity. Broome explores this through contemplative interludes featuring Tuan, a toddler he observes on a bus ride from McKeesport to Downtown, being “initiated” on what it means to be a black male by the boy’s young father. In a scene at the bus stop, Broome describes Tuan “doing all the things toddlers do with their newly found feet, pitches forward with full force onto the sidewalk, enormous toddler head first … The boy’s wails are high-pitched and

earsplitting. … ’Shake it off, Tuan,’ the young father says.” With such observations, Broome confronts his own experience. “I remember how my own

tears were seen as an affront. I remember how my own father looked at me as if I was leaking gasoline and about to set the whole concept of black manhood on fire. Stop crying. Be a man.” The description and figurative language add illustrative layers to the prose throughout.

These pivots into memory bring alive Broome’s parents and their standoffish, or accusatory, interactions towards one another. The unvarnished and unsentimental moments allow Broome to dig deep. The father is described less through physical characteristics than through his actions. “My father’s beatings were like lightning strikes. Powerful, fast, and unpredictable. He held his anger so tightly that, when it finally overtook him, the force was bone-shaking. He punched me like I was a grown-ass man. He went blind with rage and just punched me with all the strength of a steelworker. It never took more than one to lay me on my back, windless. Then he would dare me to get up. I never did.” The attacks often come after moments when Broome shows his true self, once after being caught playing with his sister’s dolls.

The parents’ marriage is described as a loveless arrangement hinging on the father’s job in a mill. When it closes, the father turns inward, blaming the mother and white folks for problems he’s unwilling to overcome. In a chapter titled “Let the Church Say ‘Amen,’” Broome gambles by shifting the point of view from himself to his mother, allowing the mother’s voice to communicate her complicated story more directly. “I like to hear my youngest boy Brian sing in the choir here. He sittin’ up there now. … That boy can sing. He put his heart and soul into it. His eyes squinched up and belting out a heavenly vibrato. The song they gave him to solo is ‘Soon and Very Soon’ and he sing it so good. When the piano player start the intro, I can just about see the electricity run through his body when he take the microphone. He look just like his Daddy. I hope he don’t turn out to be a liar like his Daddy. But men lie. That’s what they do.” This section becomes a worthwhile payoff, an exercise in listening that allows family background to flow. It also emphasizes his thankfulness for the black women who “saved my life without even knowing it.”

While the book’s tone is weighty, Broome’s touch includes the ability to make readers laugh out loud. One moment comes in his characterizing a schoolteacher, Miss Biviano. “Short and mean with a lazy eye that always confuses the class because you can’t tell who she’s talking to. You never know if she has caught you fooling around during quiet reading time or if she’s caught the person two seats down from you fooling around during quiet reading time. If she doesn’t yell out a person’s name, it makes us all look around like she called the Lotto number and we’re all trying to figure out who has the winning ticket.” Punch Me Up to the Gods succeeds by leaving its readers reeling as Broome’s deft writing proves a winner.