Read All Over the World

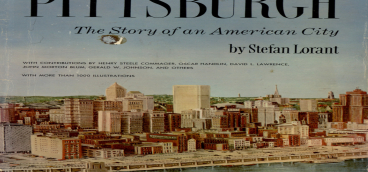

Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City was ubiquitous in Pittsburgh. It seemed as though everybody who was anybody had a copy, and some people had copies of every edition.

Previously in this series: Stefan Lorant Part III, Charming and Impossible

But what was remarkable was how well the book was known outside Pittsburgh. The first edition had become an instant classic, sought out by urban historians and ordinary people alike. Over the years it seemed as though no matter where I traveled – New York, Chicago, LA, Miami – people knew about the book and often pulled out a copy to show me their well-thumbed editions.

But my most amusing encounter with the Pittsburgh book occurred in Zurich, Switzerland, an episode I’ll call:

Felix

Back in the day I managed a family office for a very wealthy family, and that family had, among other things, extensive investments in Europe. As a result, I traveled to Zurich or Geneva – or, if I was lucky, Lugano – six or eight times a year, often staying for a week or more.

The cities of Zurich and Pittsburgh sit at roughly similar latitudes, have roughly similar climates (wet and rainy, with four distinct seasons), and are even roughly the same size. (The city of Zurich is slightly bigger than the city of Pittsburgh, but Pittsburgh’s metropolitan area is bigger than Zurich’s. If Pittsburgh were located in Switzerland it would be the country’s largest town.)

The main difference between the two cities is that Zurich is roughly one thousand years older. The first five hundred years of Zurich’s history aren’t relevant here, but sometime around 1300 AD the “modern” city of Zurich – including its name, which was originally Turicum – began to take shape.

If a Zurichois fellow happened to build a building in, say, 1306, and that building was well-constructed, as buildings tend to be in Switzerland, the odds are pretty good that the building will still be standing and still be in use today. Meanwhile, Pittsburgh’s oldest building, not counting the Fort Pitt blockhouse, is the Burke Building, constructed in 1836. As a result, the experience of visiting and having meetings in Zurich was very different, and often very disorienting.

Consider the hotel I was staying at on the trip when I visited Felix. The establishment had been built by connecting nine adjacent, medieval, tall Zurich houses in Old Town. Every room in the hotel was different. My room was on the top floor of one of the houses and it featured a very large wooden beam that ran diagonally from the floor on one side of the room to the ceiling on the other. To get from the bathroom to the bed, you had to duck under the beam. Don’t even think about getting up in the middle of the night.

The people in that part of Switzerland speak a dialect called “Swiss-German” that is virtually unintelligible to normal German-speakers. As an illustration, the morning before I met with Felix I attended an investment conference. The keynote was given by a fellow who had managed money for a private bank in Hamburg, Germany most of his career, but who had recently been lured away by a Swiss bank and had relocated to Zurich.

The fellow was describing his disorientation at finding himself in what he had thought of as a German-speaking nation. Speaking in heavily accented English, he said, “So I come to zis place and I listen to zese people talk and I say to myself, ‘Vere de hell am I, Sveden?’”

After lunch I found Felix’s office, a high-tech place located on the second floor of a sixteenth century building. I hadn’t met Felix but had spoken to him on the phone. He managed stocks in a sector of the European market that was under-represented in our portfolios, and so I was looking forward to meeting him and sizing him up as a possible money manager for us.

I pressed the bell and Felix’s assistant buzzed me in. I climbed the stairs and entered the small reception area and almost burst out laughing. There on the coffee table in the center of the room was Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City. Obviously, Felix was hoping to butter me up and get hired!

Just for the fun of it, I decided to act as though I hadn’t even noticed the book. When Felix entered the reception area to greet me, I had my back to the coffee table and appeared to be reading that day’s edition of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich’s newspaper-of-record. In fact, since the paper is published in German and I don’t speak German, I was faking it.

We introduced ourselves, went back to his office, talked about investments for an hour or so, and then Felix walked me out to the reception area. I put on my coat and made my goodbyes and still nothing had been said about the Pittsburgh book. Unable to stand it any longer, I said, with my hand literally on the doorknob, “I like your Pittsburgh book, Felix.”

“Oh!” he said excitedly. “Did you have a chance to look at it? It’s an amazing book!”

Felix heaved the book up – he was a smallish fellow and the book weighed nearly as much as he did – and began paging through it, pointing out this article, those photos. This might have gone on for hours, but I put my hand on Felix’s shoulder and said, “Felix, I’m from Pittsburgh, I know all about the book.”

Felix gaped at me in astonishment. “Pittsburgh?” he said. “I thought you were from New York!”

I shook my head and said, “Pittsburgh.” I reached over, turned toward the back of the book, and tapped my finger on page 626. It showed a nearly full-page photo of me at my family office desk, looking very much like I was having a bad attack of constipation.

Felix stared from the photo to me and back, obviously speechless. “I’ll look over my notes and give you a call in a week or two,” I told him. I bade him a cheerful “Grüezi!” and left. It wasn’t until I had descended the stairs and found myself out on the sidewalk that I remembered Grüezi is Swiss-German for “hello,” not “goodbye.”

Next up: Stefan Lorant, Part V