Butler street in Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood wears the face of a young adult enclave. Seven breweries and counting, a cider house, a craft beer store attached to an independent movie theater and bars with outdoor beer gardens flow through the neighborhood, as does a healthy population of young men with dense beards who patronize those places. But not long ago, many more of the beards seen along Butler Street were gray.

From 1970 and 1990, a heavy concentration of older adults living in the neighborhood had turned Lawrenceville into a NORC — the acronym for a demographic phenomenon known as a Naturally Occurring Retirement Community. The number of residents aged 65 or older had jumped from 13 percent of Lawrenceville’s population to more than 25 percent, which was twice the national average at the time.

Then, starting in 1990, the neighborhood steadily got younger. In 2021, less than 15 percent of the neighborhood’s population was 65 or older, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

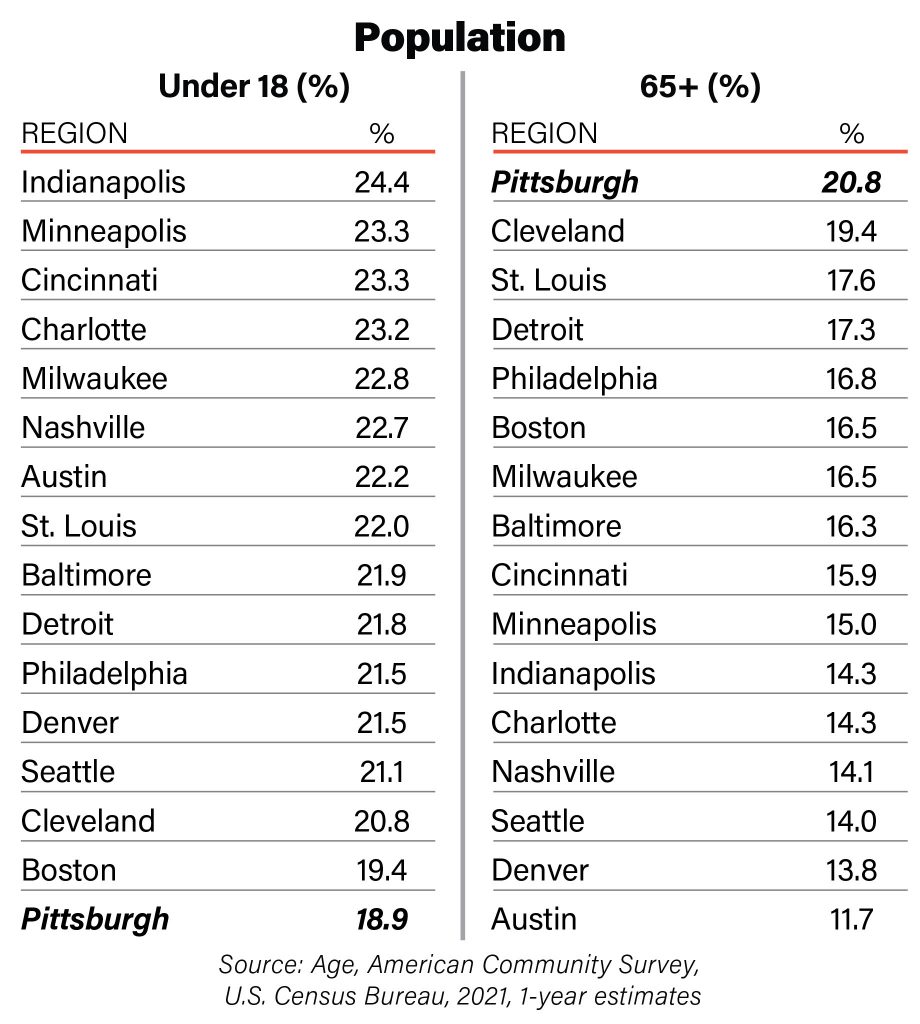

Such a reverse-aging trend, however, is an anomaly in southwestern Pennsylvania. The seven-county Pittsburgh Metropolitan Statistical Area is and has been one of the oldest regions in the U.S. since 1960. It’s a place where deaths outnumber births year after year.

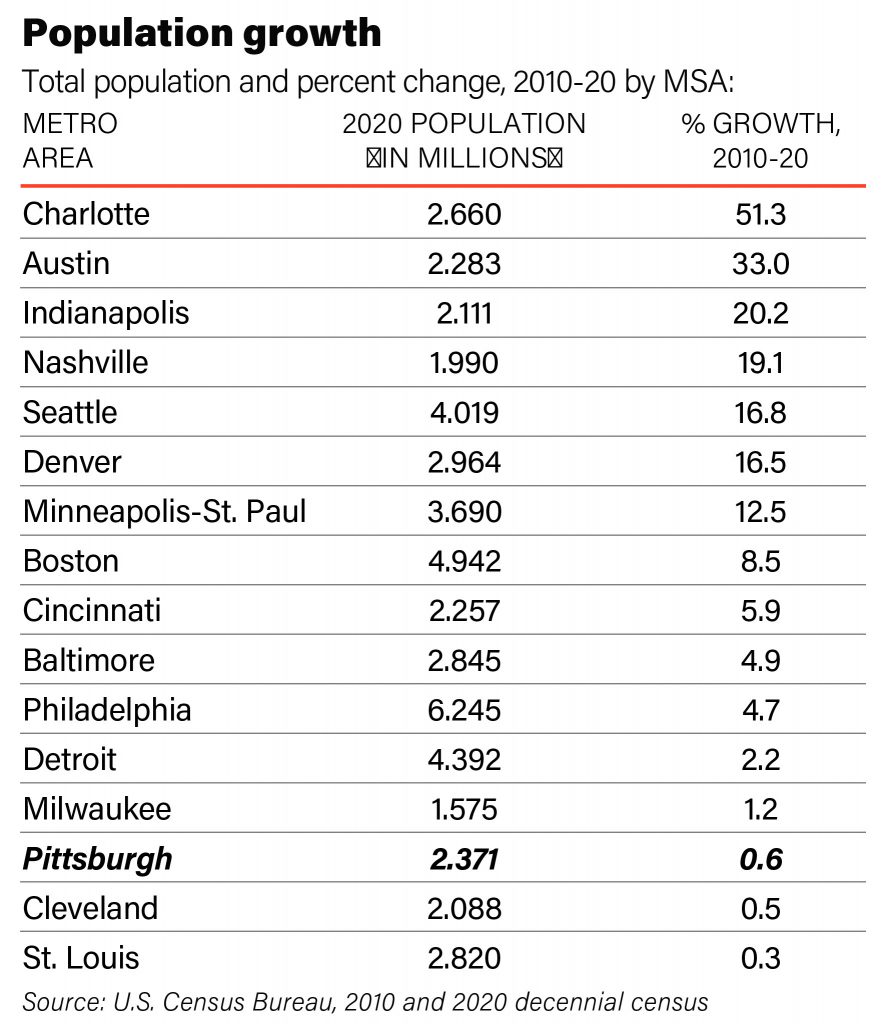

The MSA population grew a tepid 0.6 percent from 2010-2020 to reach 2.37 million people. It is one of the lowest growth rates among the 16 U.S. metro areas that Pittsburgh Today benchmarks and of little help to the region in making up lost ground. The Pittsburgh MSA population has shrunk by more than 400,000 people since 1969, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia analysis.

Recent years have witnessed the senior citizens’ share of the region’s population getting smaller and the region as a whole becoming slightly younger. But that’s about to change.

Forecasts suggest that seniors will claim an even larger share of the population in the region and across the nation, raising the stakes in the competition for younger workers and families to close a growing age gap, and posing challenges to attracting jobs, workers and more caregivers for a U.S. baby boomer generation that is 71 million strong and getting older.

We’re old

Decades after the steel industry’s collapse, southwestern Pennsylvania still wrestles with the impact that the massive loss of steel jobs had on its population. The region lost 8 percent of its population from 1980 to 1990 when 150,000 jobs evaporated. Most were young adults who left in search of better economic opportunities, taking their future families with them and widening the gap between young and old.

According to the U.S. Census, in 2021, Pittsburgh had the highest natural population loss — more deaths than births — of any American metro area. Pittsburgh lost 10,838 people, followed by Tampa/St. Petersburg, which lost 9,291 and Sarasota/ Bradenton which lost 6,643.

In Allegheny County, 19.7 percent of the population is at least 65 years old. Only the retirement destination of Palm Beach, Fla. has a greater concentration of older adults among the largest 40 counties in the U.S.

The population of a region matters. People stock the workforce. Local residents make up the biggest market for locally produced goods and services. Their numbers determine how many congressional representatives and state legislators the region sends to Washington and Harrisburg, and how many state and federal dollars it gets to pay for roads, schools, health care and other services. With slow job growth and a smaller share of people of working age, the Pittsburgh region faces unusually big challenges in growing the local economy.

Seniors might not participate in the workforce or spend as much as they did when they were younger, but they are still consumers and an important piece of the southwestern Pennsylvania economy. “Most places don’t think about it this way, but here there’s this concentration of older adults that brings in money,” said Chris Briem, regional economist at University of Pittsburgh Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR). “It’s actually a sizable amount of money that comes into the region in terms of Medicare, Social Security and Medicaid. Take them out of the equation here and we would be a smaller place, a large part of the economy would be different.”

It’s a story that will soon be told in most counties across the rest of the nation as the last of the baby boomers reach retirement age.

Future isn’t getting any younger

Total population growth has stalled across the U.S. The 2020 census showed that growth of the total U.S. population during the previous decade was the second slowest in U.S. history. And it has been further slowed by an increase in deaths nationwide during the pandemic, according to a 2023 analysis of the U.S. Census estimates by the Brookings Institution, a policy think tank.

The aging of the population is expected to make growth more difficult. In Allegheny County, the number of residents aged 65 and older is projected to swell by 50,000 between 2020 and 2050, according to a forecast of future demographic trends developed by UCSUR using a model by Regional Economic Models Inc.

The county is also expected to see a spike in its “older-old population,” which is made up of residents aged 85 years or older. “The older-old is what drives the service demand in Allegheny County and that number is going to start shooting up here for the first time in decades,” Briem said.

The number of county residents 65 and older is projected to rise from 240,000 to 291,000 by 2050, an increase of more than 21 percent, according to data from UCSUR’s recent report on the state of aging, disability and family caregiving in Allegheny County. The county’s “older-old” population is forecast to increase by more than 26,000 people — an 80 percent gain.

Southwestern Pennsylvania will have to find ways to get younger to avoid such a crisis and grow its population. With its age demographics trending as they are, that means relying more heavily on attracting people from other parts of the country, which it has struggled to do, and growing its foreign-born population, which it has done only modestly.