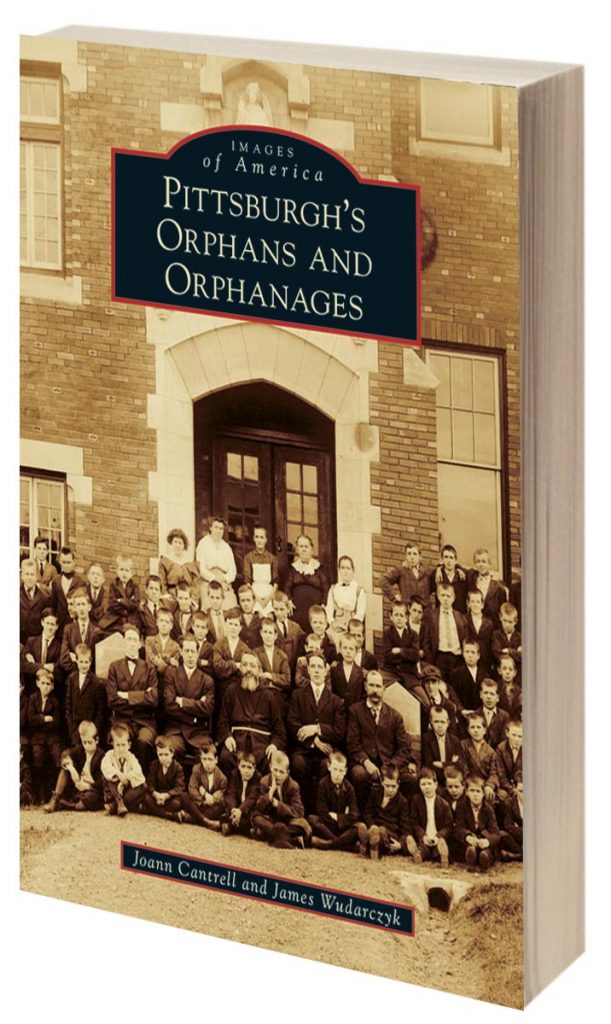

Pittsburgh’s Orphans and Orphanages

For as long as I can remember, every time my grandmother spoke of her childhood, it made me sad.

Margaret Schall, affectionately known as “Tootie,” was raised in the Odd Fellows Home for Orphans on the North Side of Pittsburgh from 1920 until 1933. She was an orphan of circumstance, rather than by the death of both parents, raised amid a multitude of children in an institutional setting from the time she was a toddler until her high school graduation because her mother could not adequately care for her.

She referred to “the Home” as a way to differentiate where she lived from how she lived, almost as a justification of her demeanor and makeup. The Home was my grandmother’s branding and it defined her more than her German ethnicity, Lutheran faith or any other genetic traits. She was an orphan — a label that became a state of mind never to be forgotten.

With mixed sentiments, I would examine old photographs of my Gram’s family and try to make sense of the puzzle of her family.

One particular photograph gave the pretense of a family, maybe one time serving as a hopeful illusion. Tootie is seen as a toddler, sitting on the knee of her grandfather, with her older siblings standing on each side. Her mother, Sarah, stands behind and holds her youngest child, not even a year old. Missing from the photo is Sarah’s husband, Bertram Schall, who died and left Sarah as a widow with five children at the age of 32.

I felt sorry for my grandmother and her siblings because there never was a family, by definition, since they never lived together in the traditional sense. Though I never knew my ancestors, I resented seeing Sarah’s mother, pictured in the photograph beside her husband, wearing a scowl on her face and cradling a cat in her arms instead of a grandchild. Observing that there appeared to be an accommodating home in the background, I always wondered, “Why couldn’t anyone help these young children? Why didn’t you do something?”

But they did do something. Not long after the family photograph was taken, my grandmother was placed in the Odd Fellows Home for Orphans in 1920 when she was just 4 years old, along with her 3-year-old sister and 6-year-old brother, after their father died. Two older sisters stayed with their mother because they were more self-sufficient and could help their mother.

I could never comprehend the dire circumstances that would lead to such a decision.

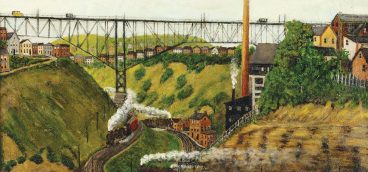

Too far removed from that era, it was difficult to understand the logic of being sent away or what it was like from another perspective. Decades later, I learned that my grandmother’s own personal story was a poignant reminder of trials faced in life, post-World War I and the years leading up to the Great Depression. Equally important, her story was the memoir of many and an important piece of Pittsburgh’s socio-economic history that has all but vanished from record books.

Descriptions from the past painted a drab picture of orphanages with an aura of unhappiness to accompany the setting. Children, often referred to as “inmates,” were assigned chores from a very young age — scrubbing floors, cleaning bathrooms, performing the daily rituals of making beds, sweeping, dusting, serving meals and washing dishes, all subject to inspection of a job done to perfection. Everything was communal and privacy was nonexistent. Children waited in long lines to use the lavatory, slept in overcrowded dormitories and lost their individuality to the uniform appearance of being an orphan. Simple comforts of childhood — being tucked into a warm bed at night, curling up in the lap of a parent, being hugged, kissed or hearing the words “I love you” were emotional supports that orphans lacked.

Research for my book, “Pittsburgh’s Orphans and Orphanages,” recently released by Arcadia Publishing’s Images of America series, validates that the experience of life in an orphanage was more common than realized.

and Orphanages

by Joann Cantrell

and James Wudarczyk

Arcadia Publishing, $23.99

In the early 1900s, orphanages in the United States housed more than 100,000 children, including thousands living in Pittsburgh. Buildings that became group homes were constructed through churches and fraternal organizations. The facilities, complete with boarding accommodations, dining halls, schools, playgrounds, and infirmaries, offered accommodations for 100 to up to 300 orphans at any given time. Single parents faced hardships during a rough economy, some as immigrant laborers who placed their children in orphanages because they had to work to make ends meet. Others were ill-equipped Civil War widows left with no alternative but to turn their children over to institutional care.

In the years after the Civil War and leading up to World War I, the 1918 influenza pandemic, and the Great Depression, orphanages were established in Pittsburgh by various groups and served all denominations.

The Protestant Home, established in 1832 by the First Presbyterian Church, was the first agency for abandoned, neglected, and orphaned children west of the Allegheny Mountains. The second orphanage, known as the Home for the Friendless, was incorporated in 1861 by the Second Presbyterian Church. The Civil War took a heavy toll on soldiers from Pittsburgh and it was estimated that the Home for the Friendless cared for more than 500 children of the men who were killed in action. For the next 100 years, both institutions continued to serve the orphan population of children within the community on the North Side of Pittsburgh.

The organization known today as Three Rivers Youth traces its origins to 1880, when local minister Reverend Fulton could not find an orphanage to provide care and shelter for a 4-year-old African American girl he found wandering the streets of Pittsburgh’s North Side. Established by the efforts of activist Julia Blair and the Women’s Christian Association, the Home for Colored Children became an unprecedented safe haven for children who were barred from all-white orphanages. Three Rivers Youth was the result of a merger between the Home for Colored Children and a child welfare service agency called the Girls Service Club, founded in 1924 and incorporated in 1932 as a home for wayward girls. The two organizations merged to become Three Rivers Youth in 1970 and it is still in operation today, serving the Pittsburgh community.

In 1891, the Jacob M. Gusky Hebrew Home and Orphanage was founded by his widow because of his passion for providing for orphans and those who were poor throughout the city. There was also a strong Catholic presence in the Pittsburgh area throughout most of the 19th and 20th centuries. As a result of concern for the welfare of orphans and homeless children, there were several orphanages established by the Roman Catholic Diocese or Catholic beneficial societies, beginning with the Sisters of Saint Joseph in Emmitsburg, Frederick County, Md., who founded Saint Paul’s Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum of Pittsburgh in 1838. The first site on Second Avenue cared only for girls, but by 1851, Saint Paul’s expanded its mission to include orphaned boys. The orphanage had a long history in Pittsburgh until a fire forced Saint Paul’s to close its doors in 1965 and the children living there were transferred to Holy Family Institute.

In 1893, Saint Joseph Protectory for Homeless Boys was established as an industrial home where boys were taught the printing trade. Six years later, it became the Toner Institute, named for Dr. James L. Toner of Westmoreland County, who provided a $140,000 fund to set up an orphanage for homeless boys.

These homes are merely a few of the numerous institutions that provided for Pittsburgh’s orphans and children in need in the late 1800s throughout the mid-1900s, aiding families as a temporary measure to deal with child care.

Thousands of children adopted the lifelong label of being a “home kid” while developing a sense of resilience and perseverance. Through shared circumstances at an early age, children learned empathy and understanding that served them well as adults.

The ability to overcome adversity was a common theme and seen in orphans such as Wilbur McKiernan. In 1927, McKiernan and his younger brother were surrendered to the Home for the Friendless on the North Side of Pittsburgh, today known as Pressley Ridge. As an adult, McKiernan never forgot the care he received as an orphan and, along with his wife, fostered children and became involved in numerous programs dedicated to the special needs of children. It is estimated that throughout their lifetime, the couple assisted in helping more than 1,800 young children. Before Wilbur McKiernan’s death in 2012 at the age of 96, he set up a trust with his estate to go to the organization that had played a pivotal role in his life.

There are numerous individuals and other unknowns who left lasting imprints as a testimony to their remarkable lives that overcame hardships and humble beginnings that began in an orphanage.

On Sept. 1, 1933, my grandmother graduated from “the Home” and, according to record, was “released to her mother.” The Odd Fellows Orphanage made good on a promise to provide an education, a strong work ethic, religious and moral nurturing and a sense of community.

As society changed after World War II, so did the need for orphanages and, one by one, the institutions eventually closed. In my grandmother’s case, she honed the skills she learned at the Odd Fellows and entered the workforce as a seamstress. Soon after, she met and married my grandfather. Together they endured the Great Depression, World War II, had two daughters, followed by a dozen grandchildren and later, so many great-grandchildren that it became a challenge to keep track of birthdays and ages. My grandparents’ longstanding marriage of six decades weathered many storms and became a relationship that set the ultimate example of perseverance and commitment.

My grandmother’s story is the memoir of many and remains an important piece of Pittsburgh’s history, along with the institutional settings that gave orphans a sense of a place to call home.