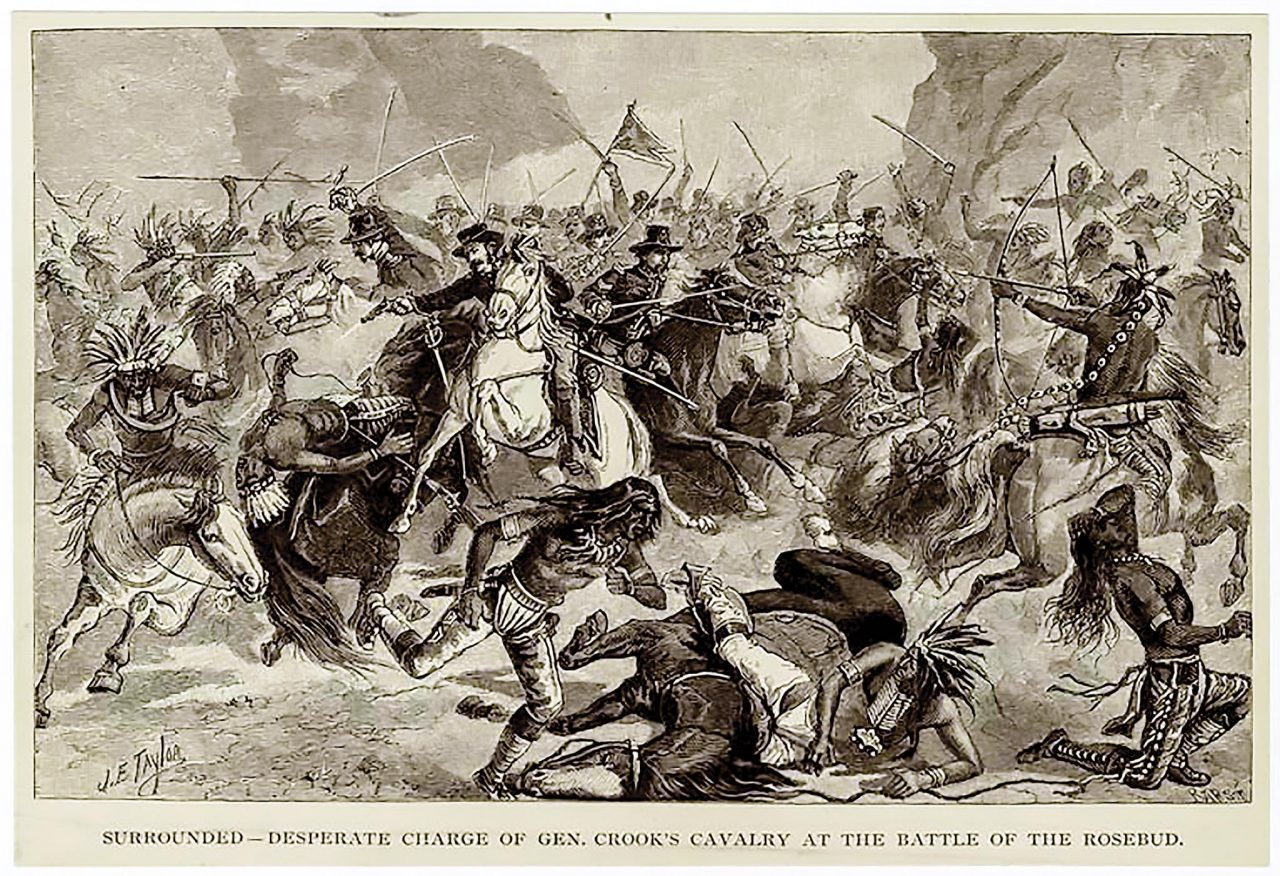

The sun burned brightly on june 17, 1876, promising a hot day in southwestern Montana. Gen. George Crook’s column of about 1,300 soldiers, friendly Indians and civilians relaxed while their horses chomped prairie grass and quenched their thirst in Rosebud Creek.

At about 8:30 a.m., as Crook played whist with fellow officers, Crow and Shoshone army scouts galloped into camp, shouting “Heap Sioux! Heap Sioux!” About 1,000 whooping Sioux and Northern Comanche charged after them, determined to wipe out the command.

“The world has heard about Custer’s Last Stand, but you can’t get there without passing or confronting the Battle of the Rosebud,” said Paul L. Hedren, author of Rosebud, June 17, 1876. “It’s the same Indian people who are fighting Crook and pretty much defeat him there, and Custer finds them eight days later and 50 miles apart and is wiped out.”

Rosebud was the biggest battle of the American West — the most combatants on the biggest battlefield — and two Pittsburghers, Lt. James E.H. Foster of I Company, Third Cavalry, and gold miner Ernest A. Hornberger, found themselves in the middle of the carnage.

After alerting the camp, the Crow and Shoshone attacked the Sioux and Cheyenne, buying precious time for the army. “If we hadn’t had them, there would have been a terrible massacre,” Hornberger wrote in a letter to his family published in The Pittsburg Evening Leader.

Crook quickly moved his units to sweep hostiles off the heights and protect his flanks and rear. This was a battle of attacks and counterattacks covering 14 square miles. Observing it all was the spiritual leader of the Sioux, Chief Sitting Bull, as Chief Crazy Horse commanded, an eagle feather in his hair and a red lightning-bolt streak on his face.

Gunshots echoed, and arrows swooshed. Trumpets blared, and Indians blew eagle wing whistles to ward off death. In the stifling heat, men sweated, and the air stank of the flesh of wounded horses.

Both sides performed deeds of valor. Chief Comes in Sight of the Cheyenne raced his horse in front of the soldiers, daring them to fire. His wounded pony threw him to the ground. As he ran to avoid gunfire, a rider pulled up, allowing him to jump on. The two safely rode away. His rescuer was his sister, Buffalo Calf Road Woman. And the Cheyenne still call it the Battle Where the Sister Saved Her Brother.

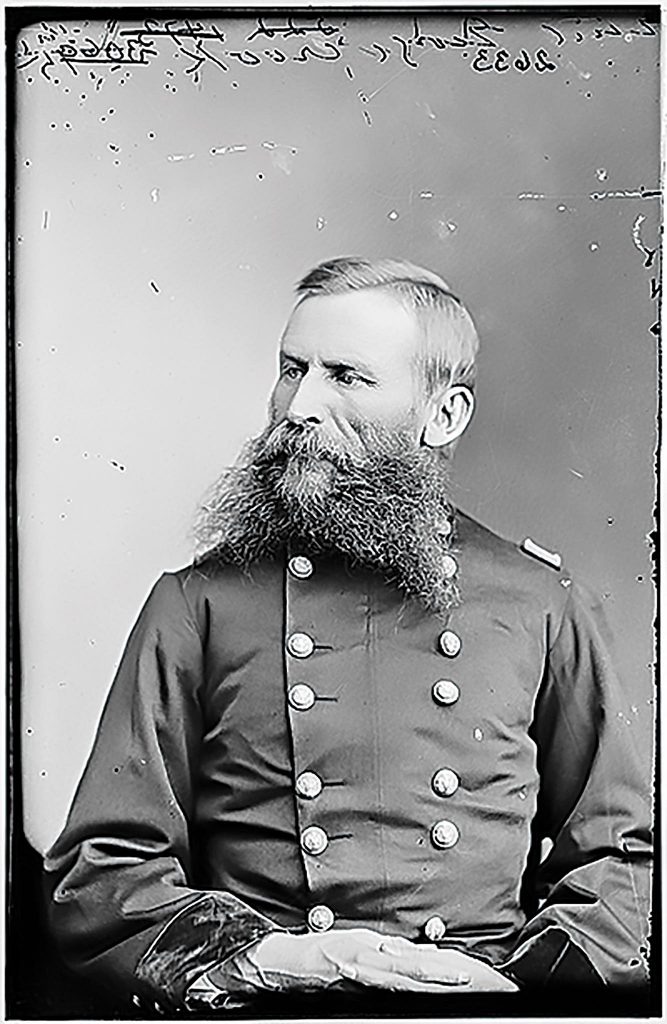

Gen. George Crook, commander of military forces at the Battle of the Rosebud, poses for a photo. Though the Rosebud tarnished his reputation as an Indian fighter, the Sioux and Northern Cheyenne surrendered the following year

Hornberger, who rode with infantry Capt. Andrew Burt, offered this description: “I was through the whole fight. The bullets were whistling around us like hail. I got a fine view of the whole thing from the top of one of the bluffs where the heavy fighting was. I stood there holding my pony, which was eating grass, and shooting whenever I had a chance.”

Many historians attribute one of the most stirring accounts of the battle, penned anonymously by “Z” in various newspapers, to Foster. He wrote that Capt. William Andrews of I Company ordered him to clear a ridge with a platoon of 18 men. Foster led the first charge, moving the Indians back “in less time than it takes to write it,” as well as successive attacks until he reached the westernmost point of the battle. Nearly stranded from the main body of troops, he noticed about 200 Indians moving to outflank and wipe out his platoon.

Foster led his platoon back slowly, then at a rapid gait down a hill through an eight-foot-deep ditch and across a nearly half-mile plain, the Indians firing in pursuit. The platoon reached Lt. Col. William Royall’s four cavalry companies at a ridge on Kollmar Creek. Far from safe, Foster and his men were about to fight in the most hellish part of the battle — the Valley of the Shadow of Death.

James Evan Heron Foster was born in Downtown Pittsburgh on June 4, 1848, into a prominent family. His father, Alexander Jr., once served as president of city common council, and his distant cousin Stephen became a famous composer. Foster attended Western University of Pennsylvania, forerunner of the University of Pittsburgh.

With the Civil War raging, the 15-year-old boy lied about his age and enlisted in a battery defending Washington, D.C. Later as a private in Company F of the 155th Pennsylvania Infantry, Foster observed as Confederates under Gen. Robert E. Lee stacked arms in surrender at Appomattox Court House.

After the war, Foster worked as a newspaper reporter and joined the Duquesne Greys, a branch of the state militia. In 1873, he entered the regular army as a second lieutenant. Recording military life in his journal, he surveyed and mapped the West to ease transportation by rail, stagecoach and horseback. He also sketched and made watercolors, some of which hang in the Nebraska Museum of Art.

On May 18, 1876, Foster and the rest of Crook’s command left Fort Laramie in Wyoming as part of a three-pronged attack to drive the Sioux onto reservations. Such incursions violated an 1868 treaty with the Sioux, who desired to keep their lands and traditional ways. Easterners, however, lured by the prospect of gold, flocked west and clashed with Indians.

Hornberger was one. Born Oct. 3, 1856, in what is now the North Side, Hornberger sold newspapers and kept books for a brewery. At age 20, he left for the Black Hills with four would-be miners from McKeesport and partnered with Colorado miner Sylvester Reese. Foster described them as “a queer-looking outfit, consisting of an ordinary farm wagon, covered, drawn by two mules,” with two pack donkeys. On June 17, as Indians sang war songs in battle, those miners must have wondered if their dreams of gold were vanishing.

At Kollmar Creek, nearly 700 Sioux fired into a line of dismounted cavalry that they outnumbered 10 to 1, by Foster’s estimate. The defenders’ ranks were thinned by details to move the wounded to doctors or hold horses for the cavalry in a ravine to the southeast. At Crook’s orders, Royall’s men fell back twice, finally along a ridge and across a football-field-length of open ground where their horses waited. This was the Valley of the Shadow of Death.

above: Lt. James E.H. Foster led several charges against overwhelming Indian forces in the Battle of the Rosebud. He later died in Oakland of tuberculosis, which he contracted during the Great Sioux War.

At each retreat, war-painted Indians wearing half-masks of wild animals rushed in to annihilate them. Foster, other officers and sergeants remained mounted, encouraging their men and presenting themselves as targets. “Yip, yip, hi-yah, hi-yah!” the attacking Indians yelled, their war bonnets streaming in the wind.

The defenders faltered. First Sgt. John Henry Shingle urged Foster’s company, “Face them, men! Damn them, face them!” An officer cried, “Great God, men! Are you going to go back on the Old Third? Forward!”

Officers and sergeants charged the Indians and rallied their men to hold the line, which fired so close that it nearly burned the noses of their enemies’ horses. The whizzing bullets sounded like “the whir of a threshing machine in full operation,” Foster wrote. One struck Capt. Guy Henry below his left eye, through his mouth and out below his right eye. Blinded and bloody, he dropped from the saddle. The Sioux galloped over him, barely missing his body, before friendly scouts rescued him.

Many others weren’t as fortunate, dying deaths of shocking violence. The near bedlam of men falling back to mount their horses emboldened the Indians, and the fighting became hand-to-hand.

Two companies of infantry, including Hornberger, moved down a hill and covered Royall’s retreat with withering volleys. Shoshone and Crow scouts rushed in, preventing a rout in the ravine. By 1:30 p.m., the Sioux left the battlefield. Crook wanted to attack a supposed village upstream, but the Indian allies refused, fearing an ambush.

For Foster and a few others, one grim task remained — retrieving the dead. Nine bodies were buried in a mass grave. Nearly 150 years later, the state of Montana is still trying to find their hidden grave.

The final toll was about 50 dead and wounded for the army and about 100 for the Sioux and Cheyenne. Nevertheless, Hedren said, “It ends up a resounding Indian victory because Crook retires from the field and licks his wounds for six weeks. Had they pressed their advantage, they would have changed the course of the war and there probably would not have been a Little Big Horn.”

For the Battle of the Rosebud, Shingle and three others won Medals of Honor. Foster received praise for his courageous charges from his superiors and in newspapers. A year after the Rosebud, the Pittsburgh Commercial and Gazette announced that Hornberger had returned home, discouraging others from gold hunting in the Black Hills.

In 1884, he moved to Nebraska and raised cattle and then to Deadwood, S.D., where he pursued grocery and mining ventures. On Dec. 7, 1899, The Daily Deadwood Pioneer-Times praised the bravery of his 8-year-old son. Ernest Jr. grabbed the reins of a runaway horse sleigh with screaming stowaways aboard and held on despite sometimes being dragged. “Two children in the sled had been too badly startled to leap, and they would have gone over the bank if the team had not been stopped.”

Hornberger served on city council and the fire department and managed the celebration of Deadwood’s silver jubilee. He returned to Pittsburgh in 1901 and worked in his brother’ real estate firm. He died Feb. 29, 1916, at his home on Bryant Street in Highland Park. He was 60. The Pioneer-Times hailed him as “one of the original pioneers of the Black Hills” and a man who “earned the confidence and the respect of his fellow citizens.”

In the summer of 1876, Foster pursued the Sioux again in the infamous Starvation March. In heavy rain and sluggish mud, without tents for shelter, the cavalry rode. Low on food, they were forced to kill and eat their horses and mules. Foster was stationed at Camp Fetterman in Wyoming where temperatures sometimes plunged to 26 below zero.

The harsh conditions forced him to take frequent and extended sick leaves. In 1881, his doctor diagnosed him with consumption, now called tuberculosis. Foster returned to Pittsburgh where he withered to 99 pounds. In April 1883, he wrote the army that he was physically unfit for duty.

About then, the Army & Navy Journal published one of his poems longing for the cavalry life he loved. The poem, “Retired,” reminisced about leading the troop “with pistols out and charging shout” and meeting his foe’s “hellish wrath.” Each stanza ends with this refrain: “Oh, comrades! It’s harder retiring; better, far better, to die.”

Foster died May 8, 1883, at his family’s home on Craig Street in Oakland. His illness from the Sioux war killed him. Comrades in the Duquesne Greys and the Press Club lamented his loss. He was just 34.

“He was a genial companion, and the years that have separated him from close contact have not allowed us to forget his work as a journalist,” The Pittsburgh Daily Post said.

Thomas R. Buecker, biographer of Foster, wrote, “An examination of this extraordinary soldier firmly secures his place in history and contributes to the legacy of the army in the West.” Buecker chose the name for his book from Foster’s faded epitaph: “A Brave Soldier and Honest Gentleman.”

The obituaries of Foster and Hornberger, though decades apart, mention their fight at Rosebud Creek. Their paths in life varied, but they endured five hours of blood and fury on the same field. They still lie on the same field — this time in Allegheny Cemetery — in peace forever.