Another year has passed in which more southwestern Pennsylvanians moved out of the region than newcomers arrived. The decades-long trend continues to slowly drain people from the region and frustrate ambitions of boosting its population.

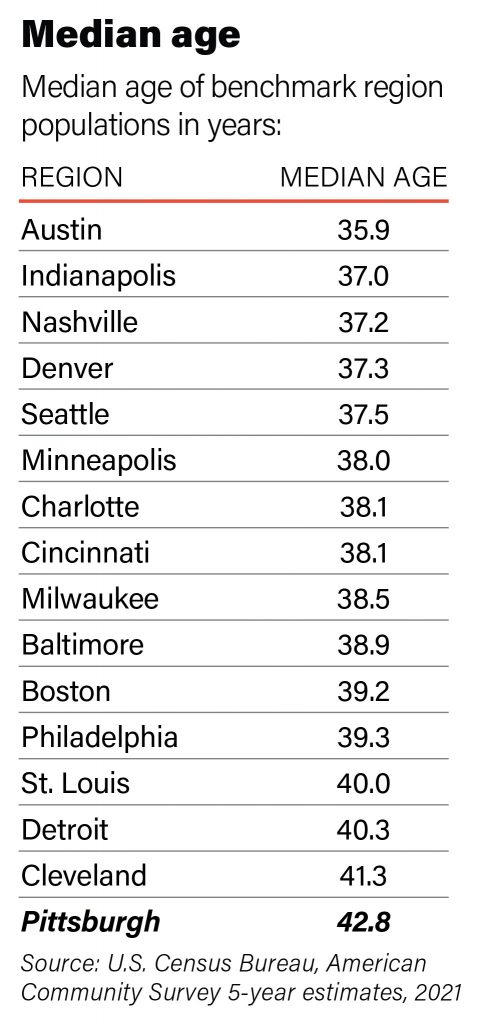

Southwestern Pennsylvania is a chronic loser in the flow of people between states that offer consistently warmer weather. And the trend appears baked into the region’s demographics for years to come. Fueling the annual exodus is the region’s exceptionally large share of residents ages 65 or older, many of whom consider pulling up stakes and heading to sunny retirement destinations once they’re out of the workforce.

Residents moving out of the region outnumbered new arrivals by nearly 4,000 from July 2021 to July 2022, the latest U.S. Census Bureau estimates suggest. “A big chunk of that is retirees,” said Chris Briem, a regional economist with the University of Pittsburgh University Center for Social and Urban Research. “The retiree migration trend is something I don’t think you’re going to change.”

That raises the stakes on reversing migration losses in other ways, such as attracting more people, especially young adults. But that’s something the region has struggled to do.

And it won’t be easy in today’s demographic climate. Americans haven’t been doing as much moving lately. Even before the pandemic, U.S. migration had fallen to a 73-year low, with only 9 percent of Americans moving each year, census data show. That’s far fewer than in the post-war 1950s, when about 20 percent of the population migrated each year.

BEHIND THE CURVE

Population experts observe a few common characteristics in the flow of people moving from one place to another in the United States. Adults under 35 are the most mobile. Economic opportunity is the chief reason most people relocate. And migration flows tend to be heaviest between places relatively close to one another.

Southwestern Pennsylvania routinely finds itself on the wrong side of domestic migration trends. The region has posted net losses for decades, a trend broken only by a five-year period of respite beginning in 2008, when slightly more people moved into the region than moved out.

The biggest exchanges of people for the seven-county Pittsburgh Metropolitan Statistical Area are among nearby metro areas, including Philadelphia, New York and Washington, D.C. But only with New York does the Pittsburgh MSA typically realize a net gain from the flow of people between the two regions.

More often, southwestern Pennsylvania gains people from migration with smaller regional neighbors, ranging from the Youngstown, Ohio, metro area and Wheeling, W.Va., just across state lines, to Pennsylvania communities east of it, including the Altoona area, and York, Adams and Cumberland counties. Several of those feeder regions are struggling with their own population issues. Wheeling lost 5.7 percent of its total population from 2010 to 2020; Youngstown, 4.3 percent; Altoona, 3.4 percent.

Migration flows to and from warm-weather states, on the other hand, tend to be one-way streets out of southwestern Pennsylvania.

Popular retirement destinations are particularly draining for the region, where nearly 21 percent of residents are at least 65 years old — one of the highest rates of seniors in the nation. Migration to Florida results in a net loss of more than 1,800 residents a year for Allegheny County alone, census estimates suggest. The county loses another 435 residents to South Carolina.

At the same time, southwestern Pennsylvania itself attracts very few seniors. Only 1 percent of seniors in Allegheny County, for example, had relocated from outside Pennsylvania the previous year, according to a recent University of Pittsburgh report on aging.

WANTED: YOUNG ADULTS

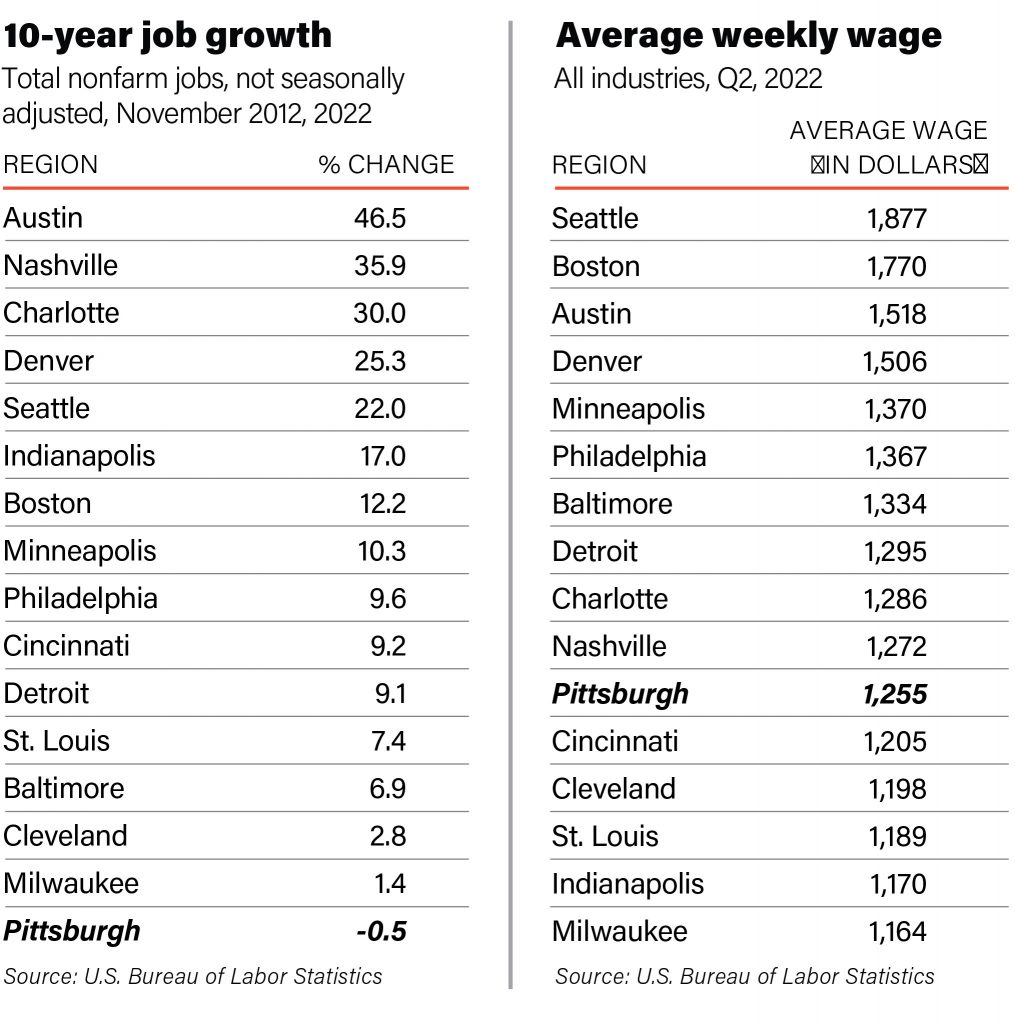

“The only way any area gets younger is to attract migration, particularly young people,” Briem said. “Economic migration is typically young people. Migration rates of people in their 20s drop off pretty dramatically, even in their 30s. If you’re a growing place that is attracting jobs, you’re probably a growing place attracting younger workers.”

Economic development groups, government officials and others have long held such ambitions for the region, only to encounter strong headwinds.

The most common reason people move to a new place is for the economic opportunities it presents — jobs, a particular industry, a workplace culture they’re comfortable with, wages and benefits as good or better than other offers. The region’s Marcellus Shale natural gas boom fed a brief period of migration gains from 2008-2013, when rapid expansion required importing workers from Texas and other mature gas and oil states. After the pace of drilling slowed, many workers returned home and the region’s migration trends fell back into negative territory.

But job growth largely has been stagnant in southwestern Pennsylvania, even before the COVID pandemic disrupted economies everywhere. The Pittsburgh MSA has fewer high-growth companies per capita than nearly all of the peer regions tracked by Pittsburgh Today. And the number of jobs at up-and-coming firms five years old or younger has fallen significantly in recent years, according to a Carnegie Mellon University report that looks at college student migration.

For decades, migration was of little concern in a region where employers generally found an ample homegrown workforce. But the steep decline of steel and other heavy manufacturing sent droves of mostly young adults out of the region in search of jobs elsewhere. Keeping them from leaving became a focus of efforts by economic development groups and others to stabilize and grow the population and labor force.

Local universities are a major source of people and highly skilled workers, as long as they stick around after they graduate. The Allegheny Conference on Community Development estimates that half of the 40,000 students who graduate from local schools each year leave the region. The Conference recently launched an initiative to explore ways to convince more of them to stay, as has Carnegie Mellon, which sees 92 percent of its students leave Pittsburgh after graduation.

Meanwhile, southwestern Penn-sylvania remains behind the curve when it comes to being a place where people decide to move to and settle in. Only 1.9 percent of the region’s population lived in another state the previous year, according to 2021 census data. The average rate of newcomers across all U.S. regions is 2.4 percent of the population. “Our obsession for 30 years has been to keep people from leaving,” Briem said. “But where we really rank low is in the flow of people coming here. We’re not attracting people from elsewhere.”