Capturing a Giant

The first painting of the entire Homestead Works

August 11, 2022

There’s never been anything quite like it.

In its heyday, the Homestead Works sprawled across 420 acres, much of it hugging both sides of the Monongahela River. Roughly 15,000 people worked there, in 450 buildings, dominating the landscape with more than 100 miles of railroad tracks and becoming so intertwined with the town that when Big Steel began to sputter in the 1970s it took much of the community down with it.

But for so many years, it was, as Rivers of Steel director Ron Baraff, put it “the American dream come to fruition.”

“The iron came from Carrie [Furnaces] and the steel produced at the Homestead Works is the steel that literally and figuratively built America in the 20th century. You have such iconic structures being built from that steel — the Empire State Building, Panama Canal locks, the Bay Bridge, Sears Tower and on and on. Not to mention the USS Missouri and the USS Olympia. These are game-changing landmarks and structures.

“But what you had at the same time was this push for the American labor movement that culminated in the Battle of Homestead in 1892, a watershed event.” Organized workers clashed with hired security personnel, resulting in 12 deaths.

So it was with some concern that Pittsburgh artist Johno Prascak undertook his opus: to create a portrait of the entire Homestead Works.

“I guess once I found out no other artist had painted the whole mill, it was very meaningful to me,” said Prascak, whose studio is in Mount Oliver.

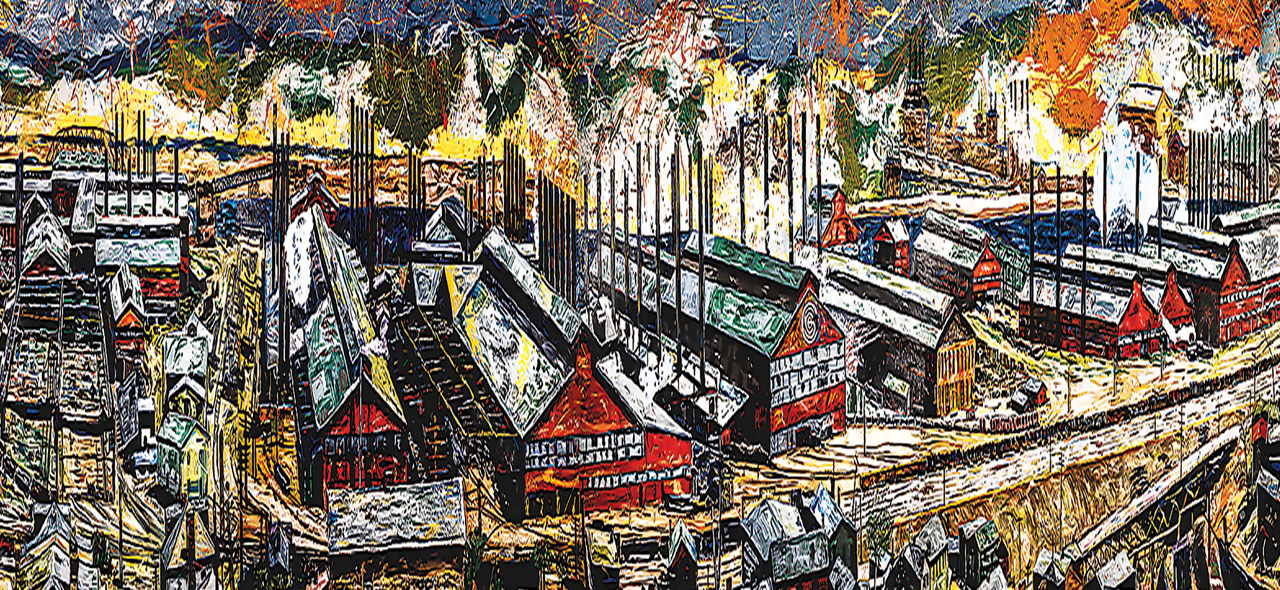

The result was 10 years in the planning, two years in the painting, often during his off hours or in the middle of the night. Eight panels — each four feet by three feet — combine for a sweeping depiction of the mill in 1926. Bold enamel sprinkled with sand from the actual mill site permeates the panoramic sweep of “Carnegie Steel-Homestead Works 1926.”

The piece is so large, it’s been on public display only twice.

“I wanted [an era] that would speak to me,” Prascak said. He ultimately settled on the site as it stood in 1926, before major WWII expansion. Although Carnegie Steel had been purchased by U.S. Steel by then, it did not change the logo until decades later. Hence, Prascak’s mill sports a “C” on one of the panels.

Baraff said previous depictions of the mill are generally “a view from afar, mostly from Calvary Cemetery. So you really just ended up with that western side. You didn’t get that full expanse.”

For research purposes, he showed Prascak a series of postcards from the now-defunct Detroit Publishing Company, which documented American life through panoramic photos in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Such images are now on display through the Library of Congress website and occasionally, Rivers of Steel sells merchandise with such depictions.

“Carnegie Steel-Homestead Works 1926” is deeply personal for Prascak, who was named for a grandfather he never met. Johno “Yonko” Prascak had emigrated from Czechoslovakia, married, found a job as a boilermaker at the mill and settled in Hazelwood.

In 1950, he collapsed at work and died after a week, likely from an enlarged heart condition.

“I was born nine years later,” Prascak said. “I’d heard all these wonderful stories of my ancestor I never met. Fast forward to this life, to my art career. I had painted a few steel mills in my time — half my work is ‘Pittsburgh’ and half is all over the charts.”

The mill project’s scope forced him to think in terms of eight, numbered pieces. Separate, but a whole. From left to right, they are numbered and smaller prints on metal are currently for sale through his web site (johnosart.com).

But the original canvases will only be sold together, he said: “They need to stay together, I emphasize that.”

The individual images can stand on their own; some depict darker, more industrial scenes. Others, more houses and trees.

“People have bought whole sets in metal, or they’ve bought individual ones. One gentleman said he liked the darker ones. Others seem to prefer the one that shows the old Carnegie Steel logo.”

For his part, Baraff said he prefers the panel with the old general office behind the mill, on 8th Avenue: “It stood until 1944, when it burned down under rather mysterious circumstances; and that’s a whole other story… but it’s neat because it has that building that few other people who are living remember.”

Prascak took a bit of artistic license for the sake of composition. First, the amount of air pollution back then was staggering, so “if I paint all the pollution, you’re hardly going to see any of the buildings.” He painted 241 smokestacks.

Second, “I am known for my color,” said Prascak, whose abstract works are on display in the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum at Texas A&M University and the NFL Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio, among others. His paintings were featured in set decoration on television shows such as NBC’s “Will & Grace” and the CBS All-Access show “One Dollar.”

Locally, it’s tough not to run into his work around town: at Heinz Field, Eat’n Park restaurants, The National Aviary, Fallingwater, the Mayor’s Office and even at the Little Sisters of the Poor. His Sarris chocolate boxes and wrappers make for Pittsburgh-centric gifts.

Prascak, an ebullient spirit, was born in Munhall and grew up in Dormont. He is self-taught, learning to paint as therapy from more than 10 years of recovery from ulcerative colitis as a teenager. His wife, Maria DeSimone Prascak, is also an artist, and their home in Mount Oliver is an eye-popping collection of eclectica.

From abstract to realistic, colors dominate Prascak’s work. He approached “Carnegie Steel-Homestead Works 1926” as a tonal puzzle. Obviously, it had to be muted. So instead of the bleak grays and browns of smoke reeking from the stacks, he went with a palette that includes oranges and greens to offset the darkness of the sky.

Prascak envisions taking “Carnegie Steel-Homestead Works 1926” on the road, where he and historians can speak to its place in western Pennsylvania life. Perhaps tie in a fundraising aspect for the host organization.

But he also hopes it will prompt others to share their family recollections.

“I’d like to have some sort of recording device to collect stories, because people are just starting to tell me all these stories about having worked in that mill, or they worked nearby in a bar, or the tavern or the base shop.

“I’ve been looking forward to showing this around, see where it goes. I’m not looking to sell it, not right now. My originals seem to find the right home over the years, which is really cool.”