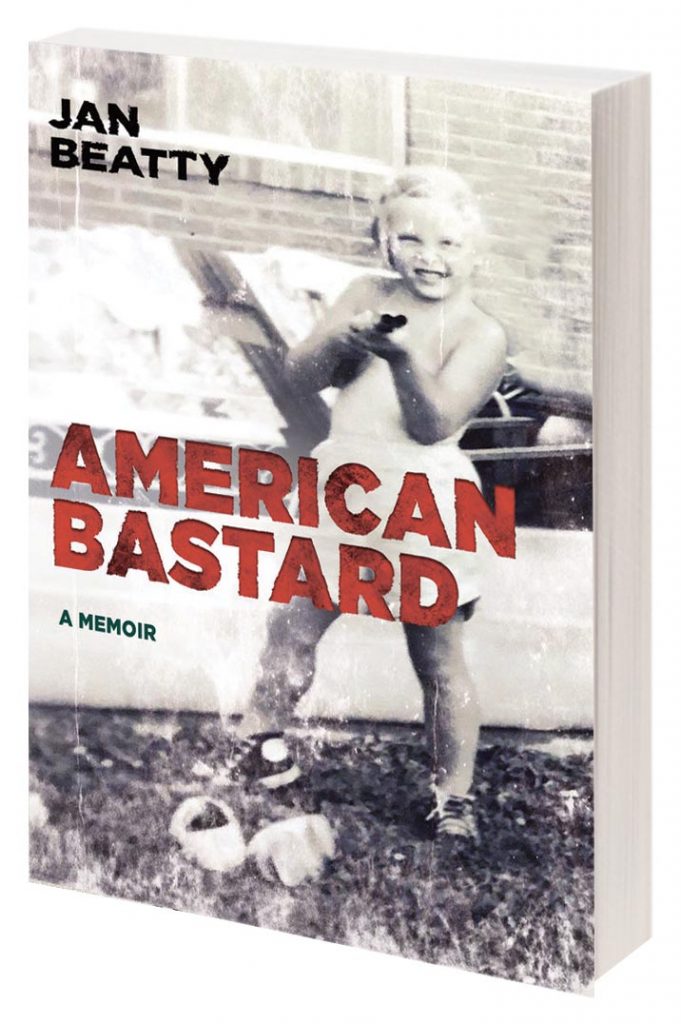

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 25,528 children were born in 1952 in Pittsburgh. One was to an unwed Garfield teen. Cared for by nuns at the Roselia Asylum and Maternity Hospital in the Hill District, she was adopted the following year by a Whitehall couple and named Janet. Since then, Jan Beatty has forged a local and national name for herself by writing the candid and compelling poems that ground her influential collections Boneshaker and The Body Wars.

Her latest book, American Bastard, winner of the Red Hen Press Nonfiction Award, is a mashup of memoir and poetry reflecting on her journey of overcoming the “erasure” of her adoption, documenting the personal stakes of this complex, often misunderstood topic. Recently retired from teaching, she’s made an indelible impact on thousands of writing students (this reviewer included) through decades as a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, The University of Pittsburgh and, most recently, Carlow University. It’s obvious she’s been heeding her own advice in American Bastard to write “what we’re afraid to write.” The memoir captures her experience with chilling authenticity, utilizing a voice that seems capable of moving mountains or moving readers to tears.

The book begins with Beatty addressing her audience “who cannot imagine what it is like not to know the woman who brought you into the world.” When she considers how the adoptee is often characterized as a “chosen baby,” Beatty calls it “the biggest lie to ever come down the pike.” Instead, she wants readers to focus on “the physical trauma of the broken bond.” It’s a powerful introduction that positions the reader for what’s to come as Beatty grapples with the implications of societal misunderstandings of the adoption process by people who “have a family, a face, a bloodline, a medical history.” The cultural and personal insights Beatty brings to a boil in American Bastard often surface with palpable anger, disbelief, and frustration as she undertakes the difficult course of securing an important part of her identity.

A powerful scene that comes early in the chapter, “Bringing home baby,” finds her at “six years old and outside playing. I remember my mother calling me in and giving me this hardcover, sea-green book with a picture of a mother in a dress, a father in a suit, and they were on their way somewhere, pushing a baby carriage. My mother told me I was adopted and to read it…I don’t think we ever talked about it again.” Beatty later adds perspective by using the words of writer Jean Lifton to explain that adoption asks the adoptee to “collude in the fiction.” The section ends with the author writing of living in Squirrel Hill with “two women — a rabid Christian and a hooker” when her given name, “Patrice Staiger,” arrives on a pre-amended birth certificate that doesn’t give her the full story.

by Jan Beatty

Red Hen Press ($15.95)

Readers expecting a straightforward narrative might be surprised at Beatty’s use of the lyrical essay that takes her poetry to another mode of expression. Eastern Iowa Review writer Deborah Tall defines this hybrid form that Beatty employs as “genre mingling, the lyric essay often accretes by fragments, taking shape mosaically — its import visible only when one stands back and sees it whole… The lyric essay stalks its subject like quarry but is never content to merely explain or confess. It elucidates through the dance of its own delving.”

The breadth of American Bastard lies in Beatty’s success at establishing thematic sections while doubling back with overlapping prose and poems to add layers of context or emphasis. This is often done through chapters that begin with poignant epigraphs ranging from Jimi Hendrix to adoption experts to Jean-Paul Sartre to nature writers such as Gretel Ehrlich, whose work introduces one section by explaining, “A captured stream is regarded as ‘beheaded’ when its headwaters are taken by its captor stream…some misfit, or underfit, streams begin this way.” Using this wide range of voices works well as tone-setter for what’s about to be revealed or the disconnection she’s endured trying to learn her background.

In the chapter “Red Sugar,” (the title poem of an earlier collection), she writes, “When I was young, I was a comet with an unending shimmering tail, and I flew over the brokenness below that was my life. I didn’t know until I was 12 that we carry other bodies inside us. Not babies, but bodies of blood that speak to us in plutonic languages of pith and serum.” The chapter continues with her approaching a woman in a restaurant she feels connected to because of “the one song I can keep as mine…some people call it eating weather,” a gut feeling telling her the woman is of the same blood, possibly a sister to the mother she’s never met. The language here and in the overlapping chapters is eerie and evocative of the body, asking questions with no sure answers. While there are commanding moments of traditional storylines, Beatty seems comfortable making this lyrical style her own.

At its core, American Bastard is an understandably existential affair. However, there’s a tonal change that’s bound to buckle a few hearts when she opens up about her bond with her adoptive father, lovingly portrayed as “my lifeline, my salvation. The one person in the world who made sense to me.” A World War II vet and a steelworker, “he knew I was lost,” buying the young Jan books and sports equipment so she could “slam balls into the house, day after day, breaking windows.” The affection for this man is palpable in different scenes. She writes of his drinking a longneck beer on a back porch, teaching the budding writer “how to tell stories,” then making her a rug by hand so “’After I’m gone, you can put this by your bed. The first thing you feel when you get up will be soft.’” It’s a stark contrast to what she won’t get from the biological parents.

The quest for understanding the circumstances of one’s birth and being are complicated for the adopted. Add the shame and stigma that once surrounded an unmarried teen mother, and it makes sense that her story will never be complete. In “I wear the red dress,” we witness the first meeting of mother and daughter in a downtown office building: “You might think it cold and strange that I’m studying her in detail while she’s crying — this woman who supposedly is my mother. But the body and blood is everything. Not knowing if there is another person out there who has your blood, looks like you. That’s everything to the adopted child. I was 32-years-old when I met my birth mother. But at this first meeting, and still today, I’m the adopted child with a couple of pieces of information.” If there’s a thesis to be had, this might be it.

When Beatty tracks down her birth father outside Boston, the three-time Stanley Cup champion and golf pro is initially warm but grows cold and distant, lending little in closure and connection. American Bastard isn’t a book with a tidy, uplifting ending the way pop culture often paints these reunions. Instead, as expected from a writer who plies in brutal honesty, readers get a gut-punch in “Dear adoptive parents.” In it, she pens an open letter to those who buy into this stereotype with eyes wide shut instead of considering the costs: “A past erased. No way back home. Maybe you’re a good person. At least the child is better off. Maybe not.” So much to consider from a writer who continues to have so much to offer.