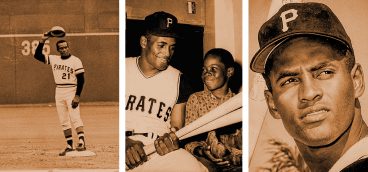

50 Years Ago, Clemente Proved His Greatness

In the spring of 1955, at the same time that I was trying out for my high school baseball team and dreaming of becoming a big league ballplayer, the Pirates were breaking in a flashy rookie outfielder from Puerto Rico.

By all accounts, Roberto Clemente was a natural. Pittsburgh sportswriters described his arm as a “rifle,” his speed as “electrifying,” and his base hits as “frozen ropes.” He was still a raw talent, but he was fun to watch, even when he made a mistake. Long-time Pittsburgh columnist Al Abrams wrote, “Every time we looked up there was Roberto, showing his flashing heels and gleaming white teeth to the loud screams of the bleacher fans.”

Clemente’s only problem was that he was beginning his career in a city with fixed racial attitudes and barriers. As a Latin American, he soon discovered that he was facing prejudice not only because of the color of his skin, but also because of his heritage and accent. Pittsburgh sportswriters went out of their way to exploit Clemente’s “broken English.” If Clemente had a good day, it was because he “heet the peetch gut.” If he started the season, slowly, which he usually did, it was because he “no run fast and no play gut” until the weather got “veree hot.”

For Clemente, 1960 was the turning point in his career. After having the best year of his career and leading the Pirates to a World Series championship, he returned to Puerto Rico believing that he had overcome racial barriers and won the acceptance of sportswriters and fans.

Less than two months later, his joy turned to anger when he learned that his teammate Dick Groat had been named National League MVP. Groat, who missed the last month of the season with a broken wrist, had won the NL batting title with a .325 average, while Clemente, playing in 144 games to Groat’s 122, had batted .314, led the team in runs batted in and was second in runs scored.

Clemente, who refused to wear his 1960 World Series ring, carried his resentment and bitterness into the next season and seasons to come and played the game as if it were a form of revenge against those who had slighted him and injured his pride and spirit. By the end of the 1960s, Clemente had won four batting titles, nine Gold Gloves, and, in 1966, was named the National League MVP.

Finally attracting national attention for his brilliant play, Clemente also began to speak out against racial prejudice. He believed that Latin American ballplayers were a minority within a minority, treated in the 1960s the way African-American ballplayers were treated in the 1950s.

In a decade characterized by political turmoil, he became the most outspoken sports figure in Pittsburgh. When Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968, Clemente was an outspoken critic of Major League Baseball’s decision to ask players and teams if they wanted to go ahead with scheduled games: “When Martin Luther King died, they come and ask Negro players if we should play. I say, if you have to ask Negro Players then we do not have a great country.”

Roberto Clemente’s performance in the 1971 World Series was electrifying and extraordinary. After watching Clemente, Roger Angell, writing for The New Yorker, claimed that “Clemente had played a kind of baseball that none of us had ever seen before – throwing and running and hitting at a level of perfection, playing to win, but playing the game almost as if it were a form of punishment for everyone else on the field.”

Facing sportswriters and the cameras in the Pirates clubhouse after the World Series victory, Clemente asked for their vindication. After 17 years, he had finally proven his greatness: “Now people in the whole world know how I play.”

A little more than a year later, on December 31, Roberto Clemente climbed aboard a DC-7 cargo plane, filled with supplies for the victims of a devastating earthquake in Managua, Nicaragua, that crashed into the sea after takeoff, killing all on board, including Clemente. His tragic death at the age of 37, so shocking at the time, has become the stuff of baseball legend and transformed Clemente into a beloved figure in Pittsburgh.

The real Clemente, however, had begun his career, in 1955, proud of his ability as a ballplayer and his heritage as a Latin American, yet emotionally estranged from America’s national game because of his race and ethnicity. Seventeen years later, after dominating the World Series, that same Clemente, when the baseball world was finally honoring his greatness, recognized his love of baseball and family as the source of his emotional strength, and asked his parents, and not the press or fans, for their blessing.

(Richard “Pete” Peterson is the author of “Growing Up With Clemente” and editor of “The Pirates Reader”)