The Amazing (and Unforgettable) Bayernhof

Tucked away on a cul-de-sac in residential O’Hara Township is a museum you’ve likely never visited. The Bayernhof Museum is the culmination of the vision of Charles “Charlie” Boyd Brown, III (1934-1999), a quirky eccentric who left a legacy for generations to enjoy.

Brown obtained his wealth by founding and running Gas-Lite Manufacturing, which made gas lamps, gas grills and artificial logs. He also was the largest shareholder of Allegheny Valley Bank and an accomplished real estate investor. He grew up in Aspinwall and graduated from Thiel College. In 1968, he rented a helicopter and flew up and down the Allegheny River, scouting locations for a home, and settled on two parcels totaling 18 acres that overlooked the Highland Park Bridge.

Instead of enlisting a construction company, he hired a 17-year-old Carnegie Mellon University student to run things. Using a pickup team of workers, the project took him from approximately 1976 to 1982 to complete. While Brown originally wanted the home to be 47,000 square feet, he was convinced to “downsize” to 19,000. The “contractors” finished one room at a time, and Brown eventually lived in one of the bedrooms, even though outside that room were only studs and planks.

The site had a massive, obstructing boulder, but Brown wanted the home to be at the edge of the property for the best view. Removing the boulder, and the small size of the crew, led to a two-year slowdown.

Brown named the home Bayernhof, which means “Bavarian courtyard,” and it contains countless architectural elements he sourced and imported from Germany to give it a more authentic appearance. With six bedrooms, three full kitchens, eight bathrooms, 10 fireplaces, 12 wet bars and stunning views, it is the ultimate party house. Each bedroom is equipped with a full wet bar, including a built-in blender. One even has an elevator. Brown’s bathroom (and much of the house) has conveniences most people could not have imagined in the early 1980s. Rooms include a gambling room, a billiards room, an office, a boardroom (which was used only twice), a wine cellar, cave and a rooftop telescope with an observatory. The room with a swimming pool boasts a wall of windows with awesome views of the Allegheny River. The house has numerous hidden doors and secret passageways.

During a two-and-a-half-hour tour, guests will learn about the wit and oddities of Brown. He was quite a jokester, and it was often difficult to separate the truth from his fibs. When he died, he left 283 of his signature Brooks Brothers blue oxford cloth shirts, the only kind he wore. (The lone exception to this was when he wore the required white shirt when he applied for membership to the Duquesne Club.)

Although he never married, he was the consummate host. Guests invited for dinner would spend hours having cocktails and hors d’oeuvres (with the Screwdrivers gradually containing less and less orange juice), followed by a tour during which the teetotaler Brown would often disappear. Then, late in the evening, a full dinner would be served in the formal dining room, which seated 16. There were plenty of bedrooms to accommodate guests who were unable to drive home.

As amazing as the house (and the stories about Brown) are, he knew he wanted the home to one day be a museum but felt it needed more of an attraction. He started collecting automated musical instruments and music boxes, including purchasing the entire contents of a music museum in Sarasota, Florida. So Bayernhof is filled with over 150 of these, primarily from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Brown procured most, and the museum continues to add to the collection when exceptional pieces become available.

It is impossible to describe the variety and rarity of this collection, which visitors can hear playing. They have been refurbished, and the foundation Brown set up upon his death continues to preserve and maintain his legacy and the museum’s contents.

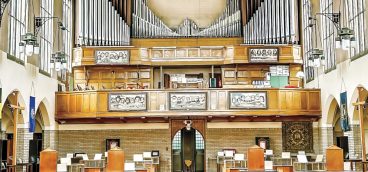

One, the Welte Cottage Orchestrion, was manufactured by Welte and Söhne from Freiberg, Germany. Orchestrions were large, elaborate, automatic music machines created for wealthy people, beginning in the mid-19th century, who wanted the orchestra experience in their homes (or palaces). These mammoth machines imitated a variety of instruments, giving the sound of an orchestral ensemble.

While the musical instruments are a real highlight of the tour, to describe them would be like attempting to describe each work of art in a museum. Similarly, to reveal any more about the house and its contents, or stories about Brown, would take away from the experience of visiting. Suffice it to say that the home, Bavarian/1980s décor, full of rare and detailed contents and fantastic stories provides a unique experience.

Docent-led tours must be arranged in advance, are for guests ages 12 and up, and are not handicapped-accessible, as the home has many staircases, some of which are spiral staircases. For more information, www.bayernhofmuseum.com, or call 412-784-4231 for reservations