Photography by Richard Kelly for Rivers of Steel

November 7, 2022

Step on board the good ship Explorer and get ready to enjoy your exciting outing on Pittsburgh’s signature rivers. No jazz combo, no dancing here, but there is a tour guide who will introduce you to the stops along your journey.

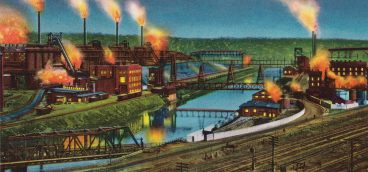

Over there are the former iron-making Carrie Furnaces spanning Rankin and Swissvale, abandoned in 1982 but now serving as a classroom of sorts for metal arts. Next up, the Pump House & Water Tower in Munhall, site of the bloody 1892 Battle of Homestead between steelworkers and Pinkertons.

If this seems like an unusual excursion, it is, because it’s not conducted by one of the well-known river tour companies. Instead, it’s a product of the Rivers of Steel Heritage Corporation, an organization whose mission is to preserve the region’s legacy as the country’s hub of steel production — and teach newcomers about that vital but nearly vanished role.

“What happened here in southwestern Pennsylvania wasn’t just important to this region, but it is a story of the building of the modern world,” says Augie Carlino, Rivers of Steel president and CEO. “When you look at all the transformative elements that came out of America in the 20th century and the late 19th century, Pittsburgh was at the center of it —not just in steel-making, but also in what became modern American business practice. Corporate boardrooms that we are so familiar with were almost invented here in Pittsburgh. It was an industrial transformation, and it was a business transformation.”

While some groups had tinkered with the idea of preserving the region’s industrial heritage and culture, the movement got its defining impetus with the 1996 passage of the National Heritage Areas Act. The legislation set the groundwork for creation of 55 such zones across the country, including the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area. The newly formed Rivers of Steel entity was designated the official steward of the heritage area and four historic sites including Carrie Furnaces; the Pump House & Water Tower; the W.A. Young & Sons Foundry & Machine Shop in Rice’s Landing, and Homestead’s Bost Building, where the organization is headquartered.

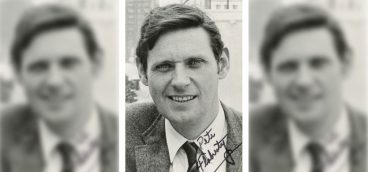

Carlino was a natural to lead Rivers of Steel. Growing up, he watched his family operate as the most important Democratic power in Pittsburgh’s 8th Ward (Bloomfield) and so cut his teeth on politics.

“I was always on the front lines in elections,” he recalls. “But what I was really intrigued by was policy making,”

He got to study that at the University of Pittsburgh, where he dual-majored in political science and rhetoric/communications. (He’s only three credits away from a third major, this one in math, which helps him manage Rivers of Steel’s annual budget of about $5.5 million and staff of more than 70.) He worked for the late Rep. Bill Coyne in Washington and later signed on with a lobbying firm. All those experiences come in handy, as Rivers of Steel interprets its mission broadly.

Tours, of course, are the most visible component, attracting up to 12,000 visitors a year before the pandemic cut into attendance. (Passengers don’t disembark at the historic sites, but Rivers of Steel also offers a walking tour of Carrie Furnaces.) Carlino notes that guests on the Explorer get a narrative of Pittsburgh’s industrial history that’s easy to digest but largely stripped of folklore: no Joe Magarac, no undue lionization of our most famous entrepreneurs.

“We’ve been told that our tours are more grounded in fact and less in folklore,” Carlino says. “But we’re not trying to give you the Ph.D. tour. We’re giving you the information in a very conversational way but in a way that doesn’t blow things out of proportion.

“We are not just a history of dead, rich, white men. If we only talk about the transformation, we would only know about Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick and Andrew Mellon. They’re important, but so are the ethnic workers and black Americans. All these people made those men who they were by their sweat and their blood and their labor. And we don’t talk about them enough.”

Following the killing of George Floyd, Rivers of Steel reviewed its scripts to make sure they accurately portrayed the experience of African-American workers in the region’s mills.

“We remind people that if you were black and worked at Carrie, you were given the most dangerous job in the mill because you were seen as the most expendable commodity in the labor force. We won’t hide from that.”

School groups get priority for tours, but when Explorer is available, private parties can — and do — rent it for weddings, banquets and other catered events and are free to bring their own entertainment. (Jazz combos and dancing after all!) Other components of Rivers of Steel’s activities may be under the radar, but they’re as important to the group’s mission. They include:

Documentation and preservation of industrial sites. Federal law requires documentation of historic sites before they’re razed for redevelopment. Working with a number of partners, Rivers of Steel helps developers do that, capturing the original sites with written, oral and video documentation … and sometimes suggesting that the developers feature artifacts from the original facilities in their plans. ”We have payroll records from U.S. Steel Duquesne Works from the first day it opened,” Carlino notes. These archives have become a unique resource for scholars, researchers, filmmakers and videographers. The collection is so sprawling that some of it is housed at Indiana University of Pennsylvania and other repositories.

Arts programs. When Carrie Furnaces shut down, “guerilla urban artists,” as Carlino calls them, infiltrated the site and used it for graffiti and other forms of artistic expression. Rivers of Steel pounced on the opportunity to establish an instructional and display site for metal arts. Carlino hopes to train people as metalworkers and welders, jobs that are in high demand but hard to fill. “We’ve demonized the trades. We’ve demonized graduating with a high school degree and going on to a trade school. We look down on that as less significant in the hierarchy of status. Yet these types of jobs are so essential to the survivability of our country.”

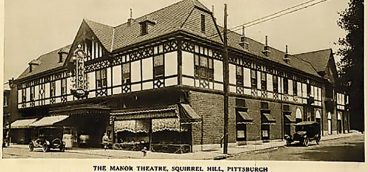

Bus tours. To spark tourism, Rivers of Steel goes beyond even its own river excursions. As what’s known as a “receptive services organization,” it packages tours for motor coach lines bringing visitors to town. Attraction tickets, restaurants, hotels — Rivers of Steel assembles the packages for its clients, who then sell them to theirs. It may seem an unlikely venture for an organization dedicated to preservation of our industrial heritage, but it’s important of itself and in paying the bills, as about one-third of the organization’s revenue comes from earned income.

A new Rivers of Steel thrust will be helping still-distressed former mill towns identify and secure grant money to assist them in attracting new businesses, sprucing up streetscapes and feeling better about their own prospects. This outreach will complement the group’s existing brownfield revitalization efforts.

“If we can create an appreciation for who we are and what we are,” Carlino says, “maybe we can stop the downturn in some of these communities. What we should never lose is the identity of who we are as people. Yet that’s what threatens our communities.

“When you see churches closing or merging or being torn down, when you lose a factory, you lose part of your identity. Our job is not to stand in the way of any transformative element but to say, as we change as a region, let’s give a nod to who we were and what role we’ve played in the development of America and the world.”