The $3,000 Hippopotamus

“Lucy is dead” was the headline of the March 17, 1902 Pittsburgh Press article that announced the passing of Lucy Juba-Nile, the popular hippopotamus that had been dwelling at the Highland Park Zoological Garden (now called the Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium) for the previous three years.

Lucy had been ill for about a week. Initially, city veterinary surgeon Dr. J.C. McNeil was asked to consult on the case. But McNeil mostly treated draft horses used by Pittsburgh’s police, fire, and public works departments, and he quickly found himself out of his element. Renowned zoologist and veterinarian Dr. William Conklin was rushed in from New York City to diagnose Lucy’s condition and advise on her care. No expense would be spared to preserve the Zoo’s most valuable asset. Conklin was one of the few people in the country with any plausible claim to hippopotamus expertise. He had achieved national fame for his role as attending physician to the hippo family at New York’s Central Park Zoo prior to his ouster in 1892 by Tammany Hall politicians.

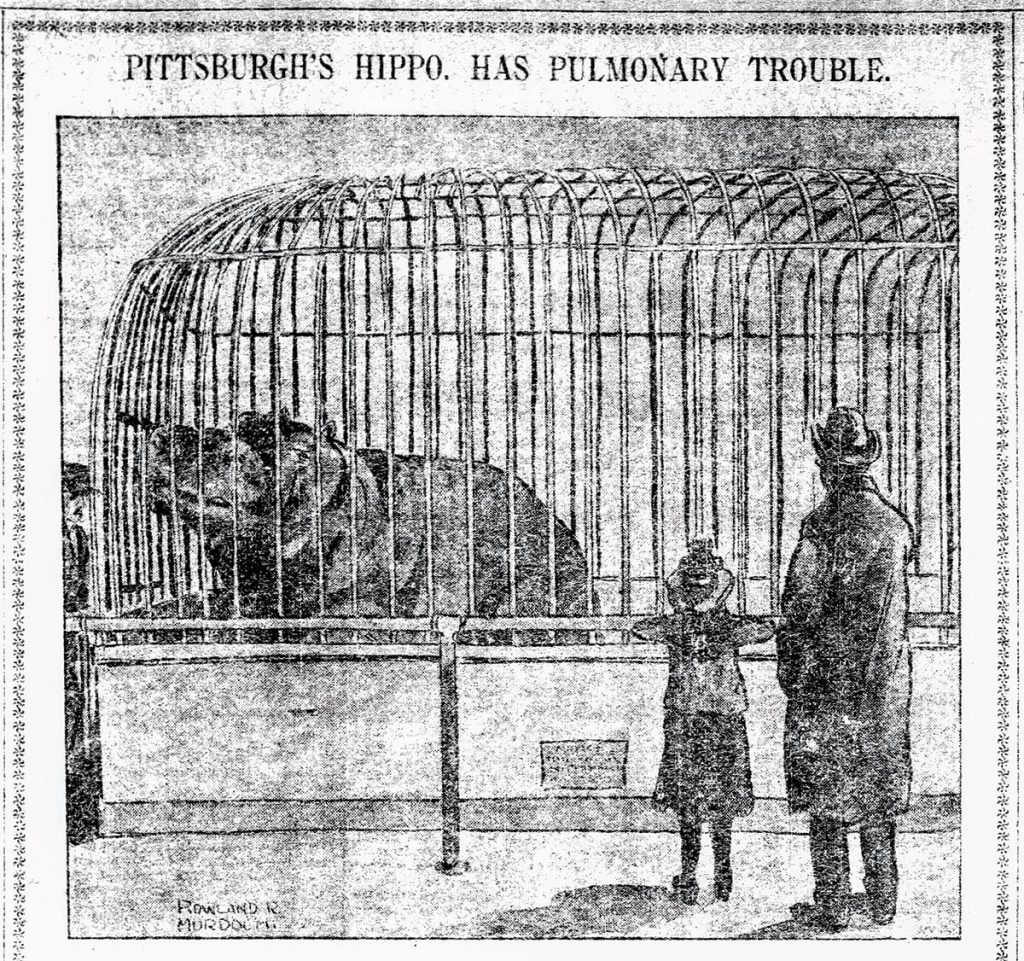

Dr. Conklin’s skills were to no avail, as Lucy was too far gone to save. First, she was diagnosed with pulmonary trouble, then “appendicitis, or something closely resembling appendicitis.” Following the post-mortem, the examiners hesitantly concluded that the cause of death was “an impaction, due to the condition of folds of skin” or maybe “inflammation and complications due to the hardening of a cancerous growth in one of the lower organs of the body.” Conklin’s reputation notwithstanding, hippopotamus doctoring at that time was really more guesswork than science.

Somewhat surprisingly, a few bigwigs from city government and top executives of Carnegie Museum were present throughout much of the ordeal. None of them had paid much attention to the recent slew of animal deaths at the zoo but this was no ordinary animal. This time was different because the latest casualty was Lucy the Hippopotamus – the Sweetheart of Pittsburgh!

Lucy had been the star attraction at the Highland Park Zoo since her arrival in January 1899. Children and adults alike had fallen in love with the cute young hippo. Adoring crowds lined up to view her from the first day she was presented to the public. The city actually went into mourning after her death; the Pittsburgh Daily Post said: “This news caused much regret, as the big animal had many friends and admirers, who felt that the loss was a personal one.”

Lucy died on a Saturday and the usual large crowds that visited the zoo on Sundays were dismayed to hear the central wing of the zoo building was closed due to the autopsy then underway on the hippo. Many people asked to be admitted to view the post-mortem and get their last glimpse of the treasured animal, but all were denied entry. Lucy’s bones and skin were turned over to Frederick Webster, taxidermist at Carnegie Museum.

Lucy was not the first hippo to set foot in the Steel City. That honor goes to the highlight of a traveling circus called “The Great Forepaugh Show,” which visited Pittsburgh in 1877. Their gaudy newspaper ads blared: “At a cost of $20,000 in gold, we have added a living male HIPPOPOTAMUS. The first one ever seen in this city, and the only one ever landed alive on this continent. IT SWEATS BLOOD! It is the GREAT BEHEMOTH OF HOLY WRIT.”

Circus ballyhoo aside, there is no doubt that in 19th century America hippopotamuses were very uncommon creatures that were sure to attract the attention of curious gawkers. In 1885 the superintendent of the Philadelphia Zoo said there were only eight hippos in the entire country. Although one or two others had been displayed briefly in Pittsburgh since the Great Behemoth of Holy Writ passed through in 1877, Lucy was the first to become a permanent resident. The events that led to her installation can be traced to the machinations of two of the most high-profile Pittsburghers of that era, Christopher Magee and William Flinn.

The story of Magee and Flinn has been told many times and does not need to be repeated here except to remind readers that they were the two most powerful political bosses in late 19th and early 20th century Pittsburgh. After long careers as party leaders and local government officials, by the 1890s both were state senators with their hands in numerous business enterprises that today would be considered serious (if not illegal) conflicts of interest.

On Christmas Eve 1895, Magee surprised the city by making a gift to the citizens of Pittsburgh on behalf of the Fort Pitt Traction Company where he was the president and Flinn was a major stockholder. Magee donated $100,000 (later increased to $125,000, equivalent to $4 million today) to construct a zoo building in Highland Park, which would be “free to the people.”

The new Zoological Garden was intended to replace the motley collection of animals at the Schenley Park Zoo, a makeshift operation including such uninspiring specimens as indigenous raccoons and groundhogs plus some less familiar species like parrots and bighorn sheep. Aside from a few broken-down lions cast off from circuses, the most noteworthy inhabitant was Gusky the elephant, a gift of Pittsburgh department store magnate Mrs. J.M. Gusky.

Oversight of the Highland Park project was entrusted to city Public Works Director Edward Bigelow, the “Father of Pittsburgh Parks” whose statue today graces the entrance to Schenley Park outside Phipps Conservatory. Bigelow was an avowed animal lover and the Schenley Park menagerie was his special hobby horse. Needless to say, he was thrilled with this new opportunity. Bigelow also happened to be Magee’s cousin, although nepotism was not really a factor in the decision to establish the facility. Rather, Magee’s gift was simply a business investment.

Lucy Juba-Nile from the Raymond E Bamrick zoological archives.

A few months after the unexpected Christmas Eve announcement, Magee and Flinn engineered the creation of the Consolidated Traction Company, which combined many Pittsburgh street railway companies (including all those leading to Highland Park) into a single citywide operation. Magee’s stipulation that access to the zoo would be “free to the people” was a compelling incentive for folks to spend a nickel on a streetcar ride to this splendid new Highland Park feature. Creating an amusement park or some other diversion at the end of their lines was a common strategy employed by traction companies to generate revenue on Sundays when otherwise their vehicles would be virtually empty as people were not going to work.

While his cousin’s public transit schemes were playing out, Bigelow and the hastily constituted “Zoo Commission” met regularly with architects to design the forthcoming structure. Building contracts were soon issued and ground was broken in June 1896. Construction was well underway by spring 1897 and Bigelow’s attention then turned to stocking the place. Much of the Schenley Park collection would be transferred to Highland Park, but the high-class zoo Bigelow envisioned would require more exotic offerings. Costs of acquiring unusual animals would be borne by wealthy patrons who would donate the funds for purchasing their favorites.

Thus, William Flinn began his quest for the seldom seem Hippopotamus amphibious. While he and Chris Magee were equal partners in the pursuit of money and power, they both liked being the big dog in every situation. Of course, each wanted to present the largest and grandest animal to the zoo. Because Magee was funding construction, he got first dibs and he chose to provide an elephant as a companion for Gusky. So Flinn decided to pursue the next best alternative – a hippopotamus. Even though it was only the second-biggest African animal, Flinn secured some bragging rights as hippos were more expensive than elephants.

By summertime Bigelow was giddily visiting the major zoos in eastern cities for advice on pricing and he initiated negotiations with the Barnum & Bailey Circus to purchase some of their unneeded stock. In September he flippantly said, “I don’t expect to work any for the next two months. I am going to the circus every day.” But as is so often the case, the prosaic calculations of accountants trumped the fanciful notions of dreamers. Bigelow was brought back to earth when City Controller Henry Gourley refused to authorize Bigelow’s acquisition of an ancient hippo from some shady circus manager. Gourley’s cost/benefit analysis suggested the decrepit animal would not live long enough to be worth the investment and he pointedly advised Bigelow to work with a more reputable animal dealer in the future.

Chastened, Bigelow took Gourley’s advice and made a connection with Carl Hagenbeck of Germany, a well-known animal collector who captured creatures in the wild and supplied them to circuses and zoos worldwide. Bigelow contracted with Hagenbeck to provide dozens of first-rate animals for the new zoo, and a high-quality hippopotamus for Mr. Flinn was near the top of his shopping list. Without much prompting, Flinn flamboyantly agreed to provide $3,000 (equivalent to $96,000 today) for the purchase of a 3-year-old hippo from Hagenbeck.

The brand new Zoological Garden was ready for occupancy in May 1898 when Flinn brashly trumpeted plans for “his” hippo: he decreed that the mighty beast would be named “Admiral Dewey” in honor of George Dewey, the national hero who had just won the Battle of Manila Bay during the ongoing Spanish-American War. Flinn thought that moniker was appropriate because he believed a hippo is essentially a water creature. (Lest we forget, the word “hippopotamus” is derived from Greek for “river horse.”)

The Highland Park Zoo officially opened June 14 with only the same familiar critters that had been relocated from Schenley Park. Hagenbeck’s first consignment of animals arrived the following week but no hippo was among them. Subsequent shipments arrived sporadically, but still no hippopotamus. At long last, Bigelow received word in October that Flinn’s hippo had been captured and would soon be on the way to Pittsburgh. But an unforeseen note was sounded: the creature Hagenbeck would deliver was described as a “baby” hippopotamus.

Flinn had been promised a 3-year-old animal, and he now balked at the purchase as the item did not meet the original specifications and the price seemed to be exorbitant for something that still needed to be fed with a bottle. Hagenbeck was a shrewd negotiator; he responded by saying the hippo was “a beauty” and because hippos “in captivity are very rare, the price may be lower than it seems.” Flinn could not renege on the deal now, so he agreed to Hagenbeck’s terms.

Regular bulletins from Hagenbeck tracked Admiral Dewey’s journey from Africa to Germany and then across the ocean to New York and ultimately to Pittsburgh. There were multiple delays along the way; as 1898 turned into 1899 impatience grew among Pittsburgh’s animal fanciers. The long-awaited hippopotamus finally arrived in Pittsburgh via train on Jan. 27 and without any fanfare was immediately whisked away to Highland Park.

If Flinn was disappointed that his $3,000 hippopotamus was only as big as a puny, half-grown cow, he never let on.

Perhaps the biggest surprise to everyone was that Admiral Dewey turned out to be a girl. Flinn’s original name now seemed to be totally inappropriate, so she was dubbed “Lucy Juba-Nile” by G. Wash Moore, superintendent of city property. She was captured in the vicinity of a village called Juba on the upper Nile River; it is unclear why Moore picked the name “Lucy.”

We will never know if William Flinn had any regrets about his philanthropic gesture, but other Pittsburghers were not at all disappointed with the size (about 600 pounds) or gender of the animal. Despite the cold weather, huge crowds turned out on Sunday, Jan. 29 to meet Lucy. The Pittsburgh Press said: “A general reception, which lasted for almost five hours, was held in order to introduce her to the people of Pittsburg[h].”

It is no wonder that so many people showed up at Highland Park on that frigid January day; for weeks the local newspapers had whetted the appetites of Pittsburghers for the new curiosity by serving up almost daily updates on the hippo’s progress. On the Friday preceding Lucy’s first public appearance the Pittsburgh Press featured a depiction of a smiling hippo on page one labeled “Our Baby Hippopotamus.” This sketch undoubtedly gave Pittsburghers a sense of pride in their city’s possession of such a scarce animal. The next day the Press published a front-page cartoon captioned “Baby Hippo at Home,” which showed other zoo animals rushing to greet Lucy. Incongruously, she was portrayed wearing a dress. Possibly the most bizarre aspect of the scene was that Lucy was shown walking on her hind legs and carrying a purse along with a baby bottle. Hopefully none of the readers truly believed that this is how hippos actually present themselves, but these two charming drawings probably contributed to the robust turnout on Sunday.

The superintendent of the zoo was Ernest Tretow, an animal trainer with a great deal of experience handling elephants. It was not long before Lucy became his special pet. Tretow delighted in rubbing his hands over Lucy’s back and making excited children squeal when he showed them his “bloody” hands. (The “blood” that hippos sweat is actually an oily substance that protects their skin much like sunscreen.) Tretow tried to teach Lucy tricks as he had long done with elephants, but he accomplished little beyond routinely inducing Lucy to leave her water tank during zoo visiting hours.

For the entire three years Lucy held court, the community never tired of her; the hippo enclosure was often the first stop during a day’s outing in Highland Park. From the moment she arrived Lucy was kept in the spotlight as the newspapers documented her life at the zoo. Like proud grandparents, Pittsburghers carefully monitored her development and voraciously devoured any new information about her. Readers were provided such minutiae as the nutritional value of her diet. Early on, a close watch was kept for signs of the eruption of teeth. The Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette’s announcement that Lucy had graduated from milk to wheat bran was quite a scoop. The hippo’s growth rate and weight gains were of considerable interest.

Lucy Juba-Nile as illustrated in a Pittsburgh newspaper in the

early 1900s.

Lucy was the most pampered creature in the city; in June 1901 the Pittsburgh Daily Post noted: “The hippopotamus at Highland Park was sick for a few days, and it was necessary to heat the water of the pool for a day or two.” The old-style zoos of the era emphasized cages for displaying the animals with little thought given to their space needs, but in September 1901 as Lucy grew larger she was granted “more commodious quarters” befitting her privileged status. By the time of her death Lucy had reached 2,500 pounds and she was still not full-grown.

While Lucy’s premature death was quite a blow for many people, reality soon set in and before long the public’s fickle attention was directed elsewhere. The newspapers tried their best to keep readers’ eyeballs focused on happenings at Highland Park, but none of the other zoo animals possessed the charisma of Lucy the hippo. Subsequent zoo reporting all too often consisted of little more than brief notices of new arrivals such as the lion cubs born in August and rattlesnakes acquired in September.

Lucy was not easily forgotten by her many fans, though. Fourteen months after her sudden death, a whimsical piece called “Hullabalooish Noise in Highland Zoo” appeared in the May 26, 1903 Pittsburgh Daily Post. It was the work of Pittsburgh florist William “Billy” Loew, who for years wrote a wildly popular humorous column under his nom de plume “The Green Goods Man.” In this particular installment, Loew spun a fantastical yarn recounting a recent trip to Highland Park when he heard a tremendous wail from all the denizens of the zoo. Upon inquiry, Gusky the elephant informed him that the distraught animals had just then been told of the demise of Lucy the hippo, whom they all loved as much as the humans did. Loew solemnly transcribed each of the sad reminiscences and tributes provided by Lucy’s peers. He then ended his tale with a sort of dirge; this is probably the only poem ever written to eulogize a dead hippopotamus:

Great grief prevailed in Highland zoo!

Boo-hoo, boo-hoo!

Beasts and birds made an awful fuss

For the dead hippopotamus;

Raised a hullabalooish cry,

Because old hippo made a die.

When they learned she’d been dead a year,

The noise they made was very queer;

With deep grief the beasts did quake

For all had missed the hippo’s wake.

Another year passed and in May 1904 Pittsburghers were stunned, if not shocked, by the disclosure that Lucy did not die from natural causes, but rather she was murdered! Specifically, she had been intentionally poisoned.

In a statement to the press, Edward Bigelow revealed that poisoning was the reason dozens of zoo animals had died several years earlier, rather than incompetent zoo management as had been suggested at the time; this had been confirmed by a veterinary expert through chemical analysis. The matter had been kept under wraps so as not to alarm the public and also to allow a criminal investigation to proceed unobtrusively.

While all these animals were dying, Bigelow received a stream of anonymous letters attacking the moral character of the city employees managing the zoo and he concluded this was somehow related to the deaths. One day he received yet another letter. But while the letter itself was obviously written by the same hand that had composed the earlier ones, the envelope in which it arrived had been addressed by someone with different handwriting. And more interestingly, this handwriting was identical to that on an envelope Bigelow had recently received from a local businessman who had contacted him concerning some unrelated city business.

Bigelow first consulted handwriting experts, who confirmed that both envelopes had been addressed by the same person. He then confronted the businessman with his evidence, but the man vehemently denied addressing the envelope containing the anonymous letter and refused to shed any light on the identity of the author of the scathing communications. At this point the unsigned letters stopped and no more animals were poisoned. Bigelow’s investigation had reached a dead end, and he gave up the inquiry as hopeless. Although Bigelow believed that the murderer was a certain disgruntled city employee, he never divulged the names of either the suspected animal killer or the duplicitous businessman.

Lucy the beloved hippopotamus was the final victim of the mysterious poisoner. The case has never been solved.

Carnegie Museum taxidermist Frederick Webster finished mounting Lucy’s remains in 1907 and she was placed on display in July. A Pittsburgh Daily Post headline provided her last burst of publicity: “HIGHLAND HIPPOPOTAMUS NOW IN CARNEGIE MUSEUM. Monster That in Life Attracted So Much Attention in Hall of Mammals.” The article reassured everyone that once again Lucy could be visited frequently “by those who made friends with the huge hippopotamus, which for so long was a feature at the Highland Park zoo.”

Now perpetually frozen in place, the late hippopotamus brought joy to Carnegie Museum visitors for many years. At some point in mid-century (museum records do not provide the exact date) the mount was removed from public display. This was probably due to a dried and cracked skin caused by temperature and humidity fluctuations accompanied by deterioration resulting from the dirt and grime of air pollution. The specimen would have become too fragile to be restored and, accordingly, it was withdrawn completely from the museum’s mammal collection.

There have been other hippopotamuses for Pittsburghers to admire at the zoo, including the pygmy hippo currently in residence, but none ever received as much interest — or adulation — as the original grande dame of Highland Park, Lucy Juba-Nile. p