You Can Go Home Again

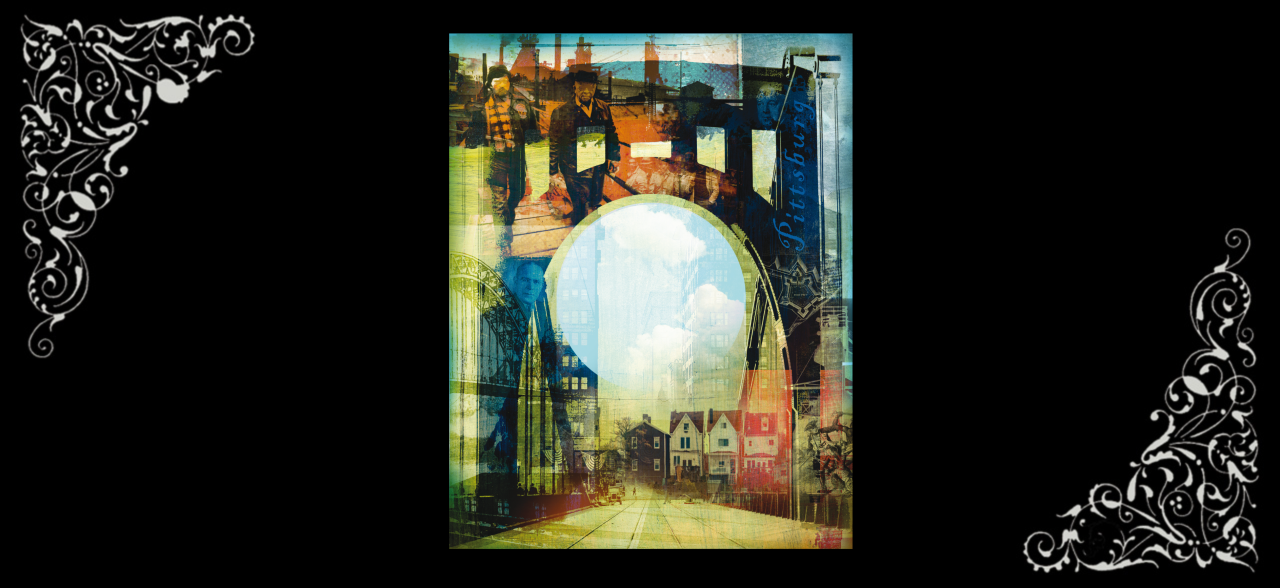

Illustration by Daniel Marsula

August 13, 2024

In 2010, Forbes magazine ranked Pittsburgh as the “most livable city in the United States.” It has fluctuated from three to nine in the rankings since then, but it consistently is among the top 10 with respect to “friendliness, economic opportunity, civic pride” and other positives. In 2010, writers came from across the country — particularly from New York — to discover what it was about Pittsburgh that made it so “livable.”

Having been born in Pittsburgh and having lived here by choice all my life, I read many of these articles and did not gain any insights into Pittsburgh’s “livability” from any one of them. Almost all of these articles seemed nothing more than “journalism on demand,” rife with statistics and supportive quotes from “authorities.” It was the language of advertising from start to finish. Shortly after that, I wrote my own essay about Pittsburgh as I knew it, and that essay was subsequently published in Carnegie Magazine.

A month after that essay appeared, a woman I did not (and still do not) know walked into my office without an appointment and said succinctly, “I read your essay in Carnegie Magazine and found it accurate. I think that you should expand it into a book on the subject.” That said, she turned and left.

As a result of her visit, I did write a book on the subject, called “The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You.” To my complete amazement, it went through five editions and, as a result, I have learned or relearned many things about Pittsburgh that reveal the “real city.” For example, I revisited my old doubts about why the Founding Fathers kept the name of William Pitt, the British prime minister, as the root of the city’s name. It had changed once already, from Fort Duquesne to Fort Pitt, after the British defeated the French in the French and Indian War. And yet, after the American victory in the War of Independence, why was Pitt’s name retained instead of removed as the Duquesne name had been?

And then there was the decades-long debate on whether to add an “h” to the Germanic “burg” so that Pittsburg would become Pittsburgh. Other “burg” cities did not seem to have a problem, since by definition a burg is simply a fortified city, but in Pittsburgh it was a battle that was not settled until July 19, 1911. A final “h” was legally added to Pittsburg to set it apart from Harrisburg, Greensburg, Sharpsburg, Mercersburg, Wilkinsburg and other burgs.

I often think that there may have been an imagined sense of “class” that was missing from “burg.” By making the case for the addition of the “h” to Pittsburg, one general suggested that the original suffix may have been “borough.” That sounded almost Scottish and could be pronounced more softly than “burg.” (I learned only recently from a scholar that Pittsburgh originally did end with an “h” before it adopted the Germanic ending.) The general’s plea was too little, too late. The state had a large German immigrant population (commonly known as Pennsylvania Dutch) and the ultimate outcome was the compromise solution of July 19, 1911. The “h” was added permanently, but with or without the “h” the pronunciation remained the same. It was really a paper victory because the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and the University of Pittsburgh had opted consistently for the “h” in Pittsburgh from the beginning.

Historians have concluded that the migration of people from Europe to the United States in the first two decades of the 20th century was one of the largest — if not the largest — in world history. Immigrants came to escape everything from starvation to political, religious and economic suppression. The Irish, for example, continued their immigration that began with the potato famine in the middle of the 19th century. By 1903, more than 11 million had migrated, with 4 million coming to America and making their homes in cities such as Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Scranton and Pittsburgh. Many went into positions of governance in the church, politics, police and fire departments and educational institutions. The Sisters of Mercy, for example, established a grade school and high school, Mt. Mercy College, and Mercy Hospital. Once when I asked former Gov. Bob Casey Sr. to explain the achievement of these Irish immigrants, he said simply, “They knew the language.”

The central Europeans (Poles, Hungarians, Slavs, Slovaks and others) came later, as did the southern Europeans, to define the population of Pittsburgh — many of them worked in the steel mills and coal mines and maintained strong family values. That same work ethic was perpetuated by their children. I once mentioned to a sports writer that some of the most outstanding quarterbacks and running backs of the mid-20th century (George Blanda, John Lujack, Joe Montana, Joe Namath, Charlie Trippi and Dan Marino) came from western Pennsylvania. He agreed, and noted that all of them regarded football as not only a sport but also a job. They worked as athletes at their positions as their fathers had worked at their laboring jobs. Lujack’s father, for example, was a boilermaker.

Then there’s the matter of Pittsburgh’s bridges. Officially, there are 446 of them. At least there were until one adjacent to Frick Park collapsed. It since has been restored, but even with 445 bridges, Pittsburgh still would have been recognized as having more bridges than any other city in the world — even more than Venice. This is occasionally disputed, but I think that Pittsburgh, having three rivers that require bridges at least 300 feet long, must have qualified comfortably when the bridges were counted officially.

Pittsburgh’s bridges were designed by some of the best bridge architects in the world, including John Roebling, who went on to design the first suspension bridge of its kind between Brooklyn and New York: the Brooklyn Bridge. David McCullough — the renowned Pittsburgh author who wrote, among his many books, “The Great Bridge” — estimated that 21 men died in construction accidents, including the bridge’s architect, John Roebling. A more interesting fact about Roebling survives from his Pittsburgh period. Told that his Pittsburgh bridge was suspected of having a defect, Roebling took it upon himself to scale the superstructure and inspect the so-called defect. Not knowing who he was, onlookers thought they were about to witness a suicide. German-born Roebling had trouble convincing them that he was who he was and that this was his bridge.

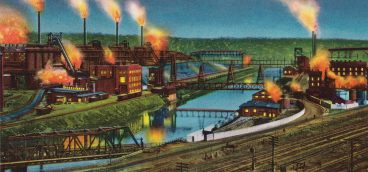

Those born in Pittsburgh in the latter decades of the 20th century and the early decades of the 21st have no memory of decades when smog (factory smoke plus fog) was the mid-century atmosphere of the city. There were many smoke-saturated days then, when it seemed like late evening at high noon. As a high school student, I remember walking to Central Catholic High School down Fifth Avenue from Shady Avenue five days a week. When the smog was heavy, I could barely see my hand if I held it out at full arm’s length in front of me. In addition, the neck side of my shirt collar would be coated with black dust.

In the forties, it became urgently obvious to everyone that something had to be done. A fatal smog (carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide and metal dust) in Donora that killed more than 20 people and sickened hundreds in 1948 was the last straw. Mayor David Lawrence, Richard King Mellon and other civic leaders initiated change, i.e., diesel and natural gas became substitutes for coal, laws against the use of soft coal were strictly enforced, and industries gradually became more reliant on technology. The end of the Second World War curtailed the military need for steel armaments and ammunition, and Pittsburgh began to grow and flourish as a center for medical research (think of the Salk polio vaccine) and care. Since 1954, there has been a 90 percent decrease in pollution by smog, amid determined efforts to keep Pittsburgh from being known as “The Smoky City” ever again.

The smog factor, created by steel production in Pittsburgh, did have a positive side despite its sickening effects. Winston Churchill stated on more than one occasion that the Second World War was won by steel. Since most of the steel used by Allied forces against the Nazis was produced in Pittsburgh, Homestead and Aliquippa, some have even been quoted as saying the war was won in western Pennsylvania.

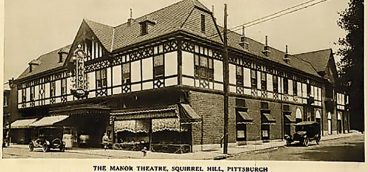

Most of the aforementioned facts are common knowledge, but what truly distinguishes the city is the effect it had — and still has — on many of its citizens. This effect seems to remain the same, although the population of Pittsburgh has shrunk since 1950 from more than 600,000 to slightly over 300,000. Because of dwindling job opportunities in the last decades of the 20th century and the opening decades of the 21st, many college graduates left the city for employment in New York, Los Angeles and other U.S. cities and abroad, and worked there until retirement.

At that point, many of the retirees decided to return to Pittsburgh to live out their remaining years. Some even moved back to the very neighborhoods and houses where they grew up and had lived before they left. What drew them back? Some say it was a sense of “home” that they found nowhere else. Whatever it was, it was more than nostalgia.

I was reminded of something I read, years past, about seniors in the Pittsburgh area being second in number only to the senior count in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. I found that hard to believe then (as I do now), but if there is any truth in it, why couldn’t it be explained in reference to the steady number of those senior retirees who returned from God-knows-where, to be combined with those who never left?

Knowing how the seemingly impossible at times becomes possible in Pittsburgh, I would be the last to doubt the possibility, no matter how presumptuous it might appear. The presumption could have been possible. After all, this is a city where Fifth Avenue crosses Sixth Avenue and no one has ever questioned the sheer impossibility of that.