When Wampum High School was Small Yet Big

In the well-trod regions of the sportswriting firmament, there is a progression in cliches used to describe successful coaches. It starts with “winning” and escalates to “renowned” and culminates with — ultima gloria — “legendary.”

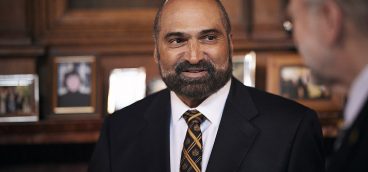

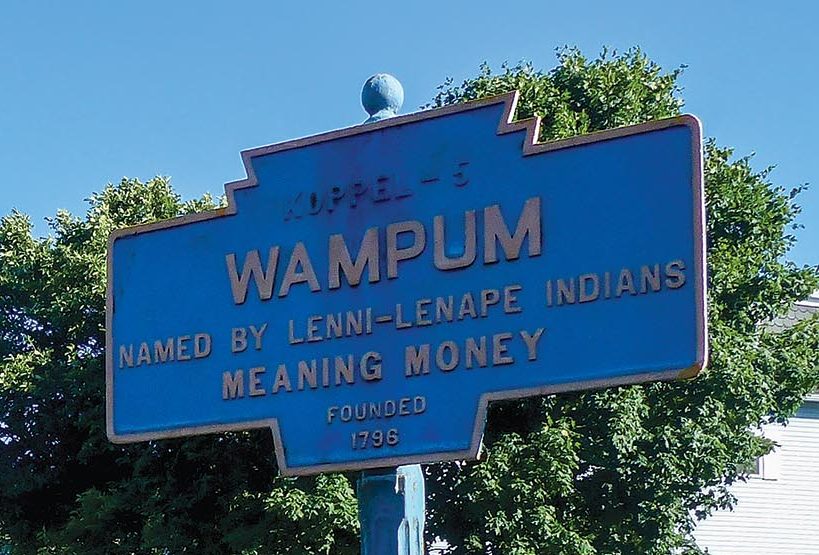

With justification, sportswriters in Lawrence County, which borders Pennsylvania and Ohio about 40 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, reflexively apply the adjective legendary to L. Butler Hennon. Hennon coached basketball at tiny Wampum High School, the smallest school in the county (and the state) for 28 years. At Wampum he was not only the basketball coach, but the baseball coach and the principal and the social-studies teacher — and the janitor for the high-school gym as well. He was immediately recognizable around town by his silver hair, softly rounded features, black metal-and-acetate spectacles, and conservatively tailored suits.

The New Castle News, the county’s major daily newspaper, once put it this way: “Among high-school basketball coaches, there’s L. Butler Hennon and then there’s everyone else. He achieved a level of legendary coaching excellence that put a hamlet of 1,100 people on the national map.”

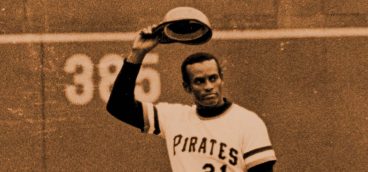

As tiny as Wampum High School was (enrollment typically numbered fewer than 120 students), it would have been even tinier without the influx of students from two neighboring semi-rural communities: Big Beaver and Chewton, the home of Dick Allen, who went on to slug 351 home runs in a 15-year Major League Baseball career, played mainly with the Philadelphia Phillies and Chicago White Sox. Allen and his four brothers, Coy, Harold, Ron, and the oldest sibling, Caesar, whose last name was Craine, were standout basketball players at Wampum from the 1940s to the early 1960s.

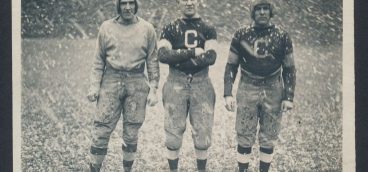

At Wampum, Hennon coached the Allens and scores of other players, drilling and motivating them to realize their potential as basketball players. In the process he accomplished these things, in competition typically against much larger schools:

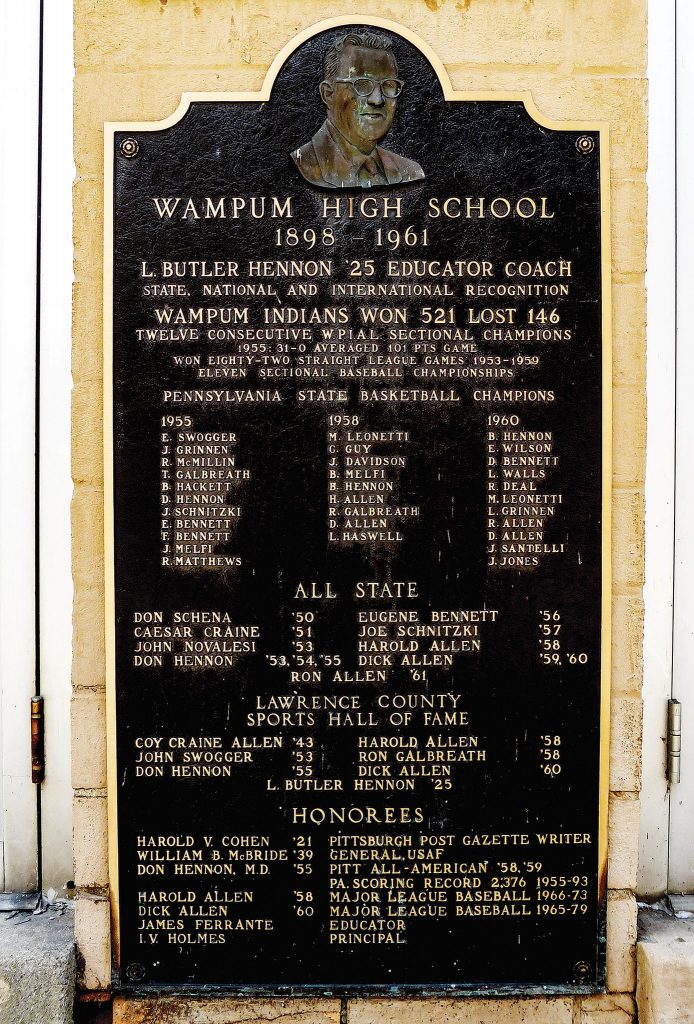

He won 521 games, including 82 consecutive league victories from 1953 to 1959, 15 section titles, and three state championships.

In what was then the Class B division in Pennsylvania high-school basketball, he developed nine All-State players, including his son Don Hennon, a two-time University of Pittsburgh All-American whose 1,841 career points set a school scoring record that lasted for 19 years.

He introduced training techniques that were considered so innovative and novel — “decades ahead of their time,” says Jim Santelli, a player on Wampum’s 1960 state-championship team — that they were featured in a photo essay in Life magazine, titled Training Tricks Help Wampum Swamp ‘Em. In practices his players, for example, wore weighted jackets, gloves, and blinders to improve their quickness and dribbling skills, and honed their leaping ability on a jumping machine equipped with an arm that flashed when touched.

Noted Life: “A casual visitor dropping in to watch basketball practice at Wampum (Pa.) High might wonder if he had wandered by mistake onto a comic skit in the school variety show. The players wear galoshes, weighted jackets, and clumsy workman’s gloves. . . . ‘When they take the weights and galoshes off, they move like elves,’ [Hennon] says.”

Such extraordinary media coverage of the team and Butler Hennon largely ended in 1961, when the Pennsylvania Department of Education merged Wampum with Ellwood City to create Lincoln High School. The Wampum Gym, located on Main Street across from the former high school, has been rechristened the L. B. Hennon Recreation Center. A bronze plaque that summarizes Wampum’s basketball history, ornamented with a sculptural relief of Butler Hennon, is displayed on the center’s exterior.

Today the center is open only occasionally. Its stillness is in sobering contrast to the time when the place resounded almost continually with noise. The gym was the venue for boisterous standing-room-only crowds at the Wampum varsity players’ home games and at other times for the squeak of aspiring younger players’ rubber-soled sneakers scraping the hardwood floor; at Butler Hennon’s decree, the gym was left unlocked day and night so that boys would be free to come and practice there at any time. (And some Wampum boys did indeed shoot hoops in the middle of the night at the gym.)

When Wampum High School ceased to exist in 1961, something vital went out of Wampum. Wampum suddenly seemed diminished, inasmuch as the Wampum High School basketball team was integral to the town’s self-image. The team matters, so we matter. Wampum without its high-school basketball team was Oakland without Forbes Field, Brooklyn without the Dodgers, Alexandria without the Lighthouse.

After the high school closed, Wampum’s population diminished as well: fewer than 700 residents live there today, down from 1,189 in 1970. The town’s shrinkage is an all-too-familiar narrative locally, reflecting an aging demographic, a declining birth rate, the loss of good-paying industrial jobs, and a once-vibrant Main Street lined with local businesses that ultimately failed.

In fact, the only business on the town’s Main Street that has survived since Don Hennon was shattering basketball scoring records in Wampum more than 60 years ago is Marshall Funeral Home. “Proudly Serving Four Generations, Since 1905,” the Marshall Funeral Home website declares. Gone are Main Street enterprises such as Scala Shoe Store, Victory Café, Al’s Super Market, Brown & Houk Hardware, Roberts Flower Shop, Wampum Hardware Co., and Repman’s drug store, all of them ultimately supplanted by the big retail and restaurant chains that moved in elsewhere.

Dick Allen, who in high school was nicknamed Sleepy for his hooded eyes, would come over from Chewton to hang out with the guys at Repman’s. A big Coca-Cola sign was bolted more than 10 feet above Repman’s storefront. The guys would say, “Sleepy, see if you can touch that Coca-Cola sign.” Sleepy was about 5’9” as a high-school sophomore, and he could easily leap and tap the sign. The sign was dusty, so Sleepy’s fingerprints were visible on it. Each year he left his fingerprints a little higher on the sign.

After graduating from Wampum High School in 1960, Sleepy went on to also leave his fingerprints in Big League baseball and did his own bit to increase national awareness of Wampum. At the end of his baseball career, when he joined the Oakland Athletics in 1977, the team’s equipment manager asked him what uniform number he wanted.

“Sixty,” Allen said, without hesitation. “For Wampum High School, Class of 1960.”

He had one other request for personalizing his Athletics uniform. He didn’t want his last name stitched on the back, he wanted something else: WAMPUM.

WAMPUM

60

It was his way to demonstrate his steadfast affection for his hometown. It was a way to validate and celebrate his feelings for a precious place far, far away from California, a place in western Pennsylvania where his mother Era imposed limits and discipline on him, where he was proud to build on the athletic legacy of the Allen brothers, where he never encountered the kind of racial prejudice that he did afterward, where he was Sleepy instead of the rebellious Bad Boy of Big League baseball, as he was often simplistically portrayed on the sports pages.

Era cleaned houses in Wampum to make a living for her five boys and four girls. “My mom did a swell job of raising us,” Dick always said. When Era died in 1995, Dick and his wife Willa moved from their retirement residence in Florida to Wampum to live in the home on the hill that he built for his mother with the $70,000 signing bonus he received from the Phillies 35 years earlier. Era sat under a huge oak tree on the hill daily and watched the crew construct the house. Her rascally Dickie — who for boyhood fun liked to swat stones with the sawed-off handles of her old brooms, resulting in some broken windows at neighbors’ homes — died in 2020 at age 78. He is buried in Clinton Cemetery in Wampum.

In his day Butler Hennon was called the Michelangelo of high-school basketball coaches. If so, his masterpiece, his equivalent of Michelangelo’s epic David sculpture, was his son Don, who in his senior year led what is considered the greatest Wampum basketball team. That 1955 team averaged 101 points per game in the regular season and steamrolled to a 31-0 record, en route to winning the WPIAL and state Class B championships.

But whereas Michelangelo’s David measures 17 feet tall, Butler Hennon’s Don is a mere five feet, nine inches in height. But Butler Hennon’s Don was a colossus in basketball at Wampum and later at Pitt, an undersized, once-in-a-generation prodigy in a sport that favors towering players.

At Wampum, Don Hennon averaged 32.3 points per game in his senior year and scored a total of 2,376 points over four years — a state record at the time. He and his Wampum teammates were so dominant in the 1955 season, he recalls, that in “one game we were winning, 89-15 at the break, and I had to sit the whole second half.” It was one of 10 games in which Wampum scored more than 100 points and Hennon played sparingly, if at all, in the second half.

Butler Hennon was defensive about criticism that his teams ran up the score against haplessly overmatched opposition. As he told Myron Cope for a 1958 Saturday Evening Post feature story: “The reason we run up high scores is that I don’t know how to teach a boy to do less than his best at all times.” He urged his players to “always play as though you’re 30 points behind. … My philosophy of coaching is to create in a boy the desire to perform as near to his capacity as he can. Look, if I’m just competitive with you and I beat you, I’m done. There is no more to do. But if I’m competing against myself, too, then I’ve always got someone to try to beat.”

For decades the Wampum players have been gathering for breakfast on the first Thursday of every month and swapping stories about the glory days. “Some of them are even true,” quips Bob Hackett, a member of the 1955 Class B state-championship team. The players originally met at Jata’s Diner in Wampum. But it closed in 2019. Then they met for a time at the Wolverine Restaurant in Ellwood City. But it closed, too. Now they meet at Hito’s Restaurant in West Pittsburg, north of Wampum.

Men who came of age in the 1950s and 1960s, especially men who played sports then, tend to be reserved and reluctant to articulate their feelings. To that generation, being perceived as touchy-feely is to be perceived as being, uh, unmanly. There’s the joke about the husband in his 70s who cared so deeply about his wife that he almost told her he loved her. So it’s striking how frequently the Wampum players of the 1950s and 1960s feel compelled to utter the L-word, the dreaded word “love,” when talking about Wampum and Butler Hennon. When “love” tumbles from their lips, it’s said freely, with sincerity and no embarrassment:

Wampum loved the basketball team, and we loved Wampum.

Butler Hennon loved his players.

On the basketball team we loved each other. There was a selfless feeling: We wanted our teammates to perform as well as we did ourselves.

Butler Hennon’s players loved him like a father. Just about all his players will say that.

When the newly consolidated Lincoln High School opened in the fall of 1961, Butler Hennon was named the school’s basketball coach. But the Lincoln players’ depth of feeling for Butler Hennon and the attitude that they brought to the basketball team somehow weren’t the same, the Wampum players say. Butler Hennon couldn’t conjure up the same coaching magic there that he did at Wampum.

Of course, even a coach as gifted as Butler Hennon can’t win championships without talented players to draw on. Despite his exhaustive attention to coaching details and his long-held contention that any boy can excel in basketball if he is willing to pay the price of hard work in mastering fundamentals, he didn’t have access to the same level of player athleticism at Lincoln that he enjoyed at Wampum. His Lincoln teams compiled a record of 106-112 in 10 seasons before he retired in 1971. Overall, he is one of 15 boys or girls basketball coaches in WPIAL history to win more than 600 games.

Declares Jim Santelli, who played on the first Lincoln team: “The Lincoln players looked at basketball differently. There were nowhere near as many dedicated players at Lincoln. There was no way in the world that Butler Hennon — or anybody else — could coach at Lincoln the way he did at Wampum. He just couldn’t coach in the same way.”

Why?

“Because it didn’t work anymore,” Jim Santelli replies. “Things change, stuff happens. That’s all there is to that.”

To Jim Santelli and his Wampum teammates, their town, their basketball team, and their coach were a testament to certain values: hard work, perseverance, civic pride, frugality, decency, a sense of community, a respect for tradition. Those values reflected a less affluent, less culturally divisive, less impersonal time. In those days, they agree, the nation was smaller and not as mobile, materialism and the social virus of income inequality were not yet rampant, the federal government was not yet the enemy, boys fought with their fists instead of with guns, and neighbors, unlike in many localities now, were more than strangers.

Of course, even growing up in such a seemingly idyllic place as Wampum at that time was no guarantee of a life of happily ever after. The lives of some Wampum players, in common with fallible human beings anywhere, have been blighted in adulthood by alcohol and drug problems, job firings, overwhelming debts, failed marriages, and unhealthy, shortened lifespans.

But the vast majority of players believe they have lived better lives because they grew up in Wampum and knew Butler Hennon. They say this, above all, was the lasting lesson they learned from their coach: Winners do what losers won’t.

The number of teammates who are grateful for Butler Hennon’s guidance and who attend the breakfasts at Hito’s Restaurant grows smaller with each passing month, as death takes more and more of them. “We are the Last of the Mohicans,” Jim Santelli says ruefully. “There were 10 people at the last breakfast.”

The Wampum players are always reluctant to leave the breakfasts, about paying their tabs and finding their car keys and driving home to get on with the rest of the day, and someone always thinks of still another anecdote to share. So they smile and settle back in their chairs at Hito’s and listen and savor the time when they were young and athletic and champions, when Main Street was flourishing, when Sleepy Allen was leaping and touching the Coca-Cola sign above Repman’s, when Wampum High School was small yet big, and when their beloved and legendary basketball coach was putting their town on the national map.