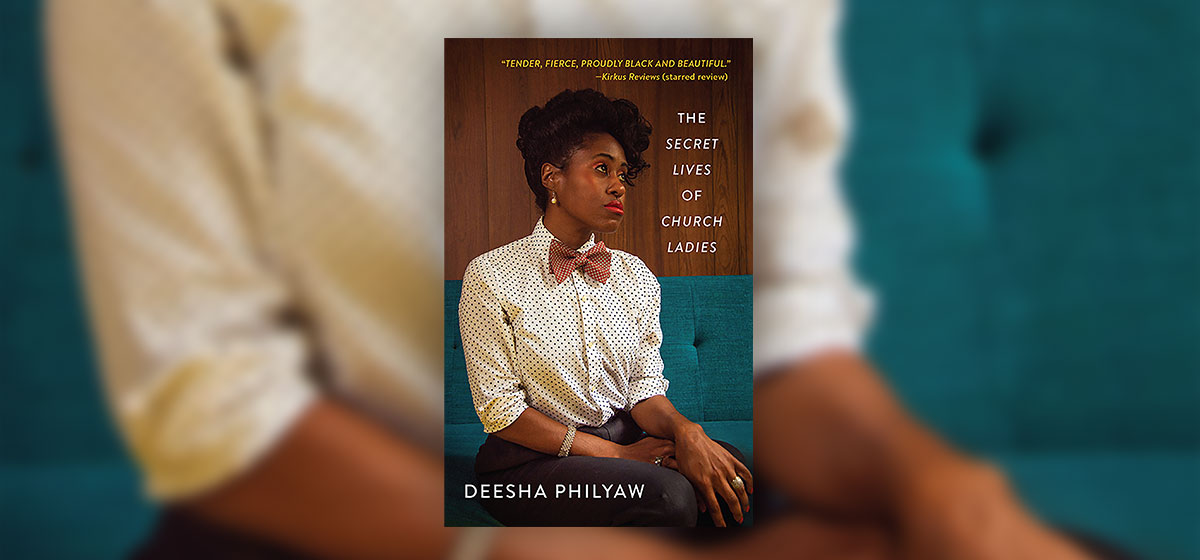

The Secret Lives of Church Ladies Wins Widespread Acclaim for Wilkinsburg Writer

To say that Deesha Philyaw is having a moment would be an understatement. Since the beginning of this year alone, the Wilkinsburg-based author has raked in numerous awards for her debut story collection, The Secret Lives of Church Ladies (West Virginia University Press, 2020), beginning with the Story Prize in March, followed by the coveted PEN/Faulkner Prize and the 2020 LA Times Book Prize: The Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction in April. The book was also a finalist for the National Book Award and is currently being adapted for television by HBO Max, with actress Tessa Thompson as executive producer.

In a climate where black artists are expected to create work focused on racist violence and trauma, thus centering what Toni Morrison called “the white gaze,” The Secret Lives of Church Ladies is a refreshing balm — a celebration of black women and girls as they explore their sexual desires and identities on the road to self-actualization. In these 10 distinctive, vibrant stories, the deftly drawn characters, many of them queer, reckon with who they truly are in the face of rigid expectations from their elders and their church.

In “Jael,” a woman discovers that her great-granddaughter is gay when she reads her diary. The narrative jumps back and forth between the great-grandmother as she grapples with how to reconnect with Jael and Jael as she lusts after the preacher’s wife and arms herself against the predatory older men in the community. The grandmother is always one step behind Jael, until a shocking act of revenge brings their stories together. “Peach Cobbler” also centers on a multi-generational relationship, though this one hinges on the narrator’s ability to keep quiet about her mother’s decades-long affair with a married preacher. Readers will find it hard not to smile at “How to Make Love to a Physicist,” a second-person story that puts them into the shoes of Lyra as she struggles to accept her body and embark on a promising new relationship.

While most of the stories have a sex scene or two, “Instructions for Married Christian Husbands” is one of the most provocative and alluring. As the title suggests, the story is a list of directives from a serial mistress to her married lovers. In a section entitled “Foreplay,” the narrator remarks, “I build monuments to my impulses and desires on the backs of men like you.”

Another bright spot is “Snowfall,” an atmospheric portrait of a woman who must let go of the past to live more fully in the present. During an icy Pittsburgh winter, college professor Arletha romanticizes her sunny southern upbringing and alienates her girlfriend Rhonda in the process. The contrasting imagery is what really shines here: the couple shoveling out their car in the morning, the icy drive to work, memories of sun tea and blue crabs and picnics. It all blends together beautifully in the final scene, where the couple enjoy a steamy lowcountry boil during a snowstorm. Philyaw writes, “I two-step my way into Rhonda’s arms, and we swing each other around and around until the crabs are ready and our faces are damp from the moist, salty air.”

The final story, “When Eddie Levert Comes,” is a departure from the rest of the collection for its third person narration and heartbreaking subject matter. “Daughter,” nameless, defined solely by her dutiful role, provides round-the-clock care to her ailing “Mama,” while her brothers shirk all responsibility. It’s a touching tribute to the lengths children go to to keep the connections to their parents alive.

Toni Morrison famously said, “I’m writing for black people in the same way that Tolstoy was not writing for me, a 14-year-old colored girl from Lorain, Ohio.” Philyaw seemed to echo this statement in a recent interview with the LA Times when she said, “Here’s what’s going to make me happy: publishing this book. And then if black women love it, I did a good job. And then if other people love it, too, awesome. I want my joy not to be dictated by something so fragile as prizes, because taste and trends are subjective. There’s going to be a time when people aren’t excited reading about black women. I’m still going to be writing about black women.” Prestigious prizes aside, it’s safe to assume that readers will be delighting in Philyaw’s work for many years to come.