Ralph Kiner, Frank Thomas and Greenberg Gardens

At the end of the 1946 season, the Detroit Tigers placed Hank Greenberg on waivers. That season, he had led the American League in home runs and RBIs, but the Tigers they felt they couldn’t afford Greenberg’s $75,000 salary. The 35-year-old Greenberg cleared waivers in the American League, and the Pittsburgh Pirates, under new ownership, headed by majority owner John Galbreath and including Bing Crosby, claimed the rights to Greenberg.

Greenberg disappointed Pirate ownership when, bitterly disappointed by the Tigers releasing him after spending his entire career in Detroit, he announced his retirement from baseball. Undaunted, John Galbreath asked Greenberg to have lunch with him in New York. Greenberg insisted that he wouldn’t change his mind, but he agreed to have lunch with Galbreath.

When Galbreath asked Greenberg for his objections to playing in Pittsburgh, Greenberg mentioned “the fences in you ballpark. Pittsburgh has a big ballpark. I’m used to a ballpark that’s 340 down the left-field line. Yours is 380 feet.” Galbreath responded by showing his willingness to accommodate Greenberg: “Don’t worry about that…. How far is that in Detroit? 340? We’ll bring the fences in so it’ll be 340. When Greenberg then asked for a salary of $100,000 and Galbreath said, “You got it,” Greenberg agreed “to play one more year.”

The distance down the left-field foul line at Forbes Field was actually 365 feet and 406 in left-center field. Between the left field foul line and the 406 mark was a mammoth 27-foot high scoreboard topped by a Gruen clock.

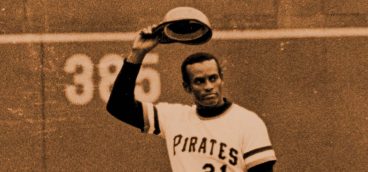

When rookie Ralph Kiner led the National League with 23 home runs in 1946, he tied Johnny Rizzo for the most home runs in a single season by a Pirate right-hand hitter. Only one other Pirate right-hand hitter, Vince DiMaggio had hit over 20 home runs in a single season (21). It had not been a park conducive to home runs.

But in 1947, to accommodate Greenberg and shorten the distance in left field to 335 feet, the Pirates put up what became known as Greenberg Gardens. Made out of plywood and chicken wire, the eight-foot fence, later heightened to 16 feet. was so flimsy that a batter once hit a ball that went through the chicken wire and was awarded a home run by the umpires. The 30-foot open space between the wall and the fence was used as bullpens by the Pirates and opposing teams.

Greenberg Gardens didn’t do much to help Greenberg, who hit only 25 home runs. It was well below his average, but good enough to set a Pirates single season record if it hadn’t been for Ralph Kiner. In his second season with the Pirates, Kiner, taking advantage of Greenberg’s tutelage and Greenberg Gardens led the National League with 51 home runs.

In 1948, Greenberg was gone, but after Kiner’s remarkable season, the Pirates kept Greenberg Gardens. Kiner responded by tying Johnny Mize for the National League lead in 1948 with 40 home runs. He would go on to lead or tie for the National League home run crown for the next four years, including 54 home runs in 1949, giving him seven consecutive seasons going into 1953. In all, he would hit 71 home runs into Greenberg Gardens.

In 1952, Kiner hit 37 home runs, his lowest total since the Pirates erected Greenberg Gardens but good enough to tie Hank Sauer for the home run title. During the off-season, Kiner got into a contract dispute with General Manager Branch Rickey that rankled Rickey, who told Kiner that the team had finished in last place with him and could finish in last place without him. True to his word, Rickey traded Kiner in mid-season 1953 to the Cubs in one of the most controversial trades in Pirates history.

Rickey may have well felt comfortable trading away Kiner because he had a rookie who could hit with power and promised to be the next Ralph Kiner. He was also likely to be a fan favorite because he was a Pittsburgh kid who grew up in the Oakland area, only a baseball throw from Forbes Field.

***

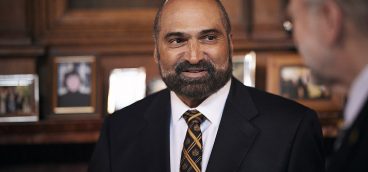

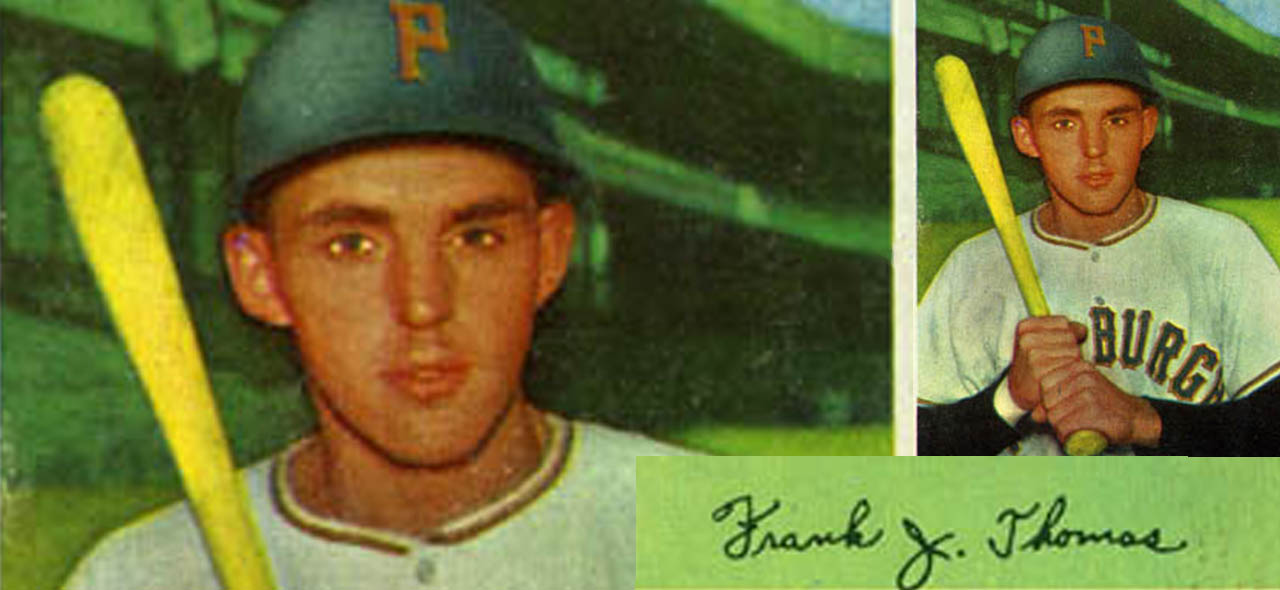

Born on June 11, 1929, Frank Thomas was the oldest son of four children in the family of Bronaslas and Anna Thomas, who had an arranged marriage. A Lithuanian immigrant whose family name was Tumas, Thomas’ father lost his right arm in a work accident, but ruled the family with his strengthened left arm. Thomas once described his father as “very strict and very mean.”

Thomas claimed that he blocked out “most of the memories” of his childhood, but he did remember his uncle Mike “playing baseball with me and walking three miles to Schenley Park every Saturday and playing ball all day long.” He also attended Pirate Knothole games. His mother said that he “never went to bed without a bat or a ball in my hand.”

When Frank Thomas turned 12, his father decided that his oldest son should become a priest and sent him to a seminary in Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada. While at the seminary, Thomas played baseball against local high school teams, and so dominated the games with his power pitching and hitting that when he reached 17, he decided, much to his father’s displeasure, to return home and “become a major league baseball player.”

Back in Pittsburgh, Thomas started out playing sandlot ball with a team sponsored by a local butcher shop until he played his way to a spot on the Little Pirates, a team sponsored by the big league Pirates. He hit so well with the Little Pirates that he attracted bird dogs and scouts. The Cleveland Indians made the best offer, but Thomas wanted to play with his hometown team. When the Pirates agreed to pay off the remaining $3,200 mortgage on his family’s house, Thomas signed a contract with them on July 23, 1947, just six months after he left the seminary. For Frank Thomas, “it was like a miracle.”

His journey through the minors league was slow and frustrating, despite his consistent outstanding play. Twice in his minor league years, when he wasn’t promoted or worse yet was demoted, he decided to quit baseball, but his parents and his wife Delores talked him out of it. He started out in 1948 with Class D Tallahassee, and after playing well, advanced in 1949 to Class B Davenport and Waco; but despite hitting over .300, he was shipped back the next season to Tallahassee. After being invited to spring training with the Pirates in 1950, he stood out and was briefly promoted to Class AA New Orleans, before he was demoted to Class A Charleston.

When the Pirates repeated the pattern in 1951, an angry and frustrated Thomas went home, but after talking to his wife, he reported to Charleston. After playing well, he was finally promoted in late season to the Pirates, where he played in 39 games, batted .264 with 9 doubles and 2 home runs. In 1952, the Pirates, to Thomas’ continuing frustration, sent him back to New Orleans, but the demotion turned out to a blessing. While the Pirates, at 42-112, had their worst season in its modern franchise history, Thomas had a terrific year at New Orleans, hitting 35 home runs with 131 RBI’s. Despite Pittsburgh reporters wondering why Thomas was still in the minors, he wasn’t called up until the last few weeks of the 1952 season, but Thomas believed he finally “made the team.”

***

When Thomas finally made it to the Pirates, he received some excellent advice from Ralph Kiner: “Watch the way they pitch me, because you’re a home run hitter, and that’s the way they’re going to pitch to you, too.” Thomas claimed that he never imitated Kiner, but like Kiner, he cocked his right elbow at shoulder-length, swung with a slight uppercut, and was a dead-pull right-hand hitter. He also had strong hands, the result of playing softball without a glove in his youth, and would challenge opposing players, like Willie Mays, to throw a ball that he couldn’t catch barehanded.

In his first full season with the Pirates, Thomas, playing in only 128 games, hit 30 home runs and drove in 102 runs. After Rickey traded Kiner in 1953, Thomas, who had been playing part-time and had only 4 home runs, became the team’s starting center fielder, batted fourth, and went on a home run and RBI tear.

Unfortunately for Thomas, the Pirate decided that, if they could do without Kiner, they could also do without Greenberg Gardens. They torn down the Gardens immediately after the Kiner trade, but they had to put it back up when they were told no team could change the dimensions of its ball park during the season. When the 1953 season ended, they torn it down again. Many in Pittsburgh were happy because they believed that Greenberg Gardens was an eye sore, but Frank Thomas was not one of them.

Without Greenberg Gardens, Thomas hit only 23 home runs in 1954 — the same number of home runs hit by Kiner in 1946, the only year he didn’t have the help of Greenberg Gardens. Thomas went on to hit 25 home runs in 1955 and 1956 and 23 in 1957. He led the Pirates in home runs in each of those seasons with the exception of 1956, when Dale Long, a left-hand batter, hit 29 home runs in the season, setting a major-league record when he homered in eight straight games.

Like Kiner, Thomas, in his early years, had trouble negotiating his contract with Rickey. At one point Thomas refused to report to the Pirates and worked for a while at T& T Hardware, located on the South Side and owned by his uncles. When Rickey criticized Thomas, comparing him negatively to Kiner. he responded, “if you’re going to compare me, give me the same opportunity. Put back Greenberg Gardens for me and I’ll hit you 50 home runs because I can tattoo that scoreboard.”

If there was any doubt that he was capable of matching Kiner’s numbers, Thomas, in 1958, had a season that was a remarkable display of power. He hit 35 home runs, 12 more than any right-hand batting Pirate had hit in one season without the help of Greenberg Gardens, and drove in 109 runs. The Pirates, led by Thomas, had their first winning season in nine years and finished in second place behind the Milwaukee Braves. After his greatest season in baseball, Thomas finished fourth in MVP voting behind Ernie Banks, Wille Mays, and Hank Aaron. Only Banks, with 47, hit more home runs in 1958 than Thomas.

Throughout his years with the Pirates, Thomas felt that he was never appreciated or properly rewarded. He played well in the minors, only to suffer through an up-and-down struggle to reach the big leagues. He hit with power in his first full season with the Pirates, only to see Greenberg Gardens torn down. Though he hit with consistent power in his seasons with the Pirates, he faced season after season of frustrating negotiations with Pirate management. And after he had his greatest season in 1958, the Pirates traded him.

In January 1959, Thomas was in Germany with Joe Garagiola and other players to give baseball clinics at air force bases. It was in Germany that he found out that he had been traded, along with three other players, to the Cincinnati Reds for Smoky Burgess, Harvey Haddix, and Don Hoak.

Pittsburgh was home for Thomas. He and his wife Delores lived in Greentree, where, wanting a big family they would eventually raise eight children. Years later, Thomas still recalled his pain and anger when he learned about the trade: “I was upset to be traded away from the town where I live in. And I would miss the fans, though most didn’t appreciate me until after I was gone — when I returned to Forbes Field I would get ovations.” He also admitted that the Pirates were close to the World Series: “I always say my claim to fame was I was traded for the guys who helped bring the pennant to Pittsburgh.”

After a disappointing 1959 season, the Pirates went on to win the National League pennant and World Series in 1960, but the road for Thomas was frustrating and mostly disappointing. In his remaining eight years in the major leagues, plagued by injuries, he played for six different teams and was twice traded to the Cubs.

In the best of his remaining years, he hit 21 home runs with the Cubs in 1960, 25 with the Milwaukee Braves in 1961, and 34 with the New York Mets in 1962. He was teammates with Ernie Banks and Hank Aaron, but also had the unfortunate distinction of playing for the awful expansion Mets in their first two years, only to be traded in mid-season 1964 by the Mets to the Phillies team that suffered an end-of-the season collapse that cost them the pennant and Thomas’s chance to play in the World Series.

After being released by the Cubs in 1966, Thomas, after 16 years in the major leagues, retired at the age of 37 and returned to his home in Pittsburgh. Over the years, he developed close ties with his former teammates, Dick Groat and Roy Face, and, as an active member of the Pirates’ Alumni Association, participated in various Pirate charity events, including its annual golf tournament.

When the Pirates announced their inaugural Hall of Fame class in 2022, Thomas was not included, though, no doubt he will be in the future. Unfortunately, Thomas will not live to see that moment. He passed away on January 16, at the age of 93.

Kiner, with the help of Greenberg Gardens in all of but one of his six full seasons in Pittsburgh hit 301 home runs in a career that took him to the Hall of Fame. Frank Thomas without the help of Greenberg Gardens in all but one of his five full seasons in Pittsburgh, hit 163 home runs, second only to Kiner on the all-time Pirate list when he was traded away. With the help of Greenberg Gardens. Ralph Kiner became a home run king during his days in Pittsburgh. Without Greenberg Gardens, Frank Thomas became Pittsburgh’s uncrowned home king. The distance separating the careers of Hall-of-Fame Kiner and an often overlooked Thomas was only 30 feet.