Especially nowadays, you get a different kind of art in times of war, variously patriotic, indignant and escapist. When these elements exist together, they are best nurtured by the democratic postulate, which, in times of war, itself hangs only by the skin of its teeth.

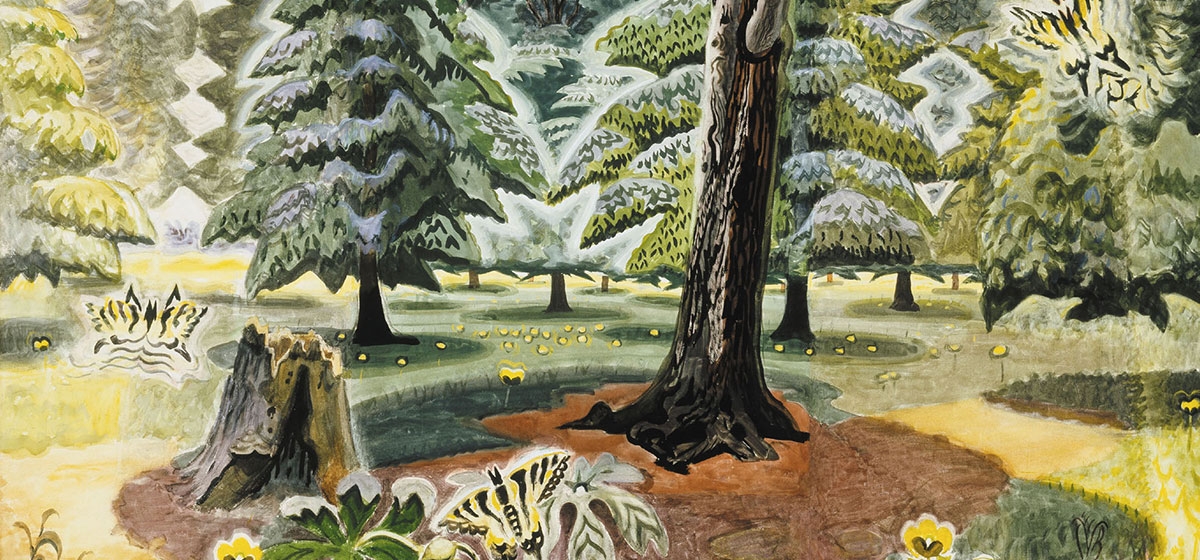

Painting in the United States 2008, the superb show at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg (until Oct. 19) is, despite its title, notabout now, with its particular wars, but about then, 60 years ago, during WorldWar II. From 1939 to 1949, the Carnegie International exhibition series became a victim of war, forced to contract to a national survey only. From 1943 to 1949, seven exhibitions dedicated to a survey of painting in the United States annually selected 300–350 artists for inclusion, unjuried, except for the prizes. (Note, not sculpture, not Canada, but travelers to the United States, such as James McBey, a Scot, and Salvador Dali, a Spaniard, were oddly slipped into the galleries.) Just fewer than 50 paintings in the Greensburg show epitomize this series. It is a remarkable achievement both in quality and concision.

And it comes at a particular moment in time. The art of the Forties has had a rough time of it in the ensuing 60 years. The New York School, which had little impact on these exhibitions, was to launch American painting of its own kind into international stardom. Its artists, Pollock, de Kooning and Rothko, made little impact in Pittsburgh. And after that, Pop. And then the deluge.

I have always thought that it is collectors who save the soul of art (except when they are too rich or confused to think straight), aided by a determined group of scholarly curators and a small body of specialist dealers. All are represented in this show. They have managed to remind many museums of the treasures that have often been languishing in their storerooms. The art of the Forties in America is on the map again, traveling in great museums throughout the world, in strange, quirky frames of wormy chestnut and other such whimsies. (I wish we could train our catalog designers to illustrate work in their original frames when possible.)

In the Greensburg show, you could be forgiven for forgetting that wars were being fought, so warmly were the home fires burning. Grandma Moses’s evocative Old Checkered House, 1853, (1945-46) and Hovsep Pushman’s Past Golden Days, (1945) look back sentimentally. The Depression, too, is viewed through the eyes of social realism in Ben Shahn’s Father and Child (1946) and Robert Gwathmey’s Hoeing, (1943). These two aspects of realism are confounded by Charles Sheeler’s flawless Winter Window, (1941). Surely this, like his photographs, ultimately depicts the purest reality? Not so. Inside the window is one kind of truth, beyond it quite another, plausible but impossible.

So although realism is to all intents and purposes the prevailing force in this exhibition, one soon recognizes that the underlying psychological cross-currents of sentiment, anxiety and fear, which are characteristic of the 20th century as much as this single decade, make all these paintings deep and complex. Realism is dished up variously. Providing these different slants are Edward Hopper and his poetic omissions, Edward Cadmus with a rather uncharacteristic work, George Tooker, more uncomfortable than usual, and Jack Levene eliding realism and satire in a spectacular painting.

Surrealism too, that foreign implant, is represented by Dorothea Tanning (women figure well in this selection, as they did at the time).

Abstraction? Always the rub! The catalog does not hide from us the prejudices of the local and national press at the time. The Pittsburgh Press questioned the “wisdom—or sanity—of awarding the $1,000 first prize… to an abstract.” But here the selectors, John O’Connor and Homer Saint Gaudens, stood their ground.Arthur G. Dove’s Arrangement in Form II, (1944) is not alone in the show, although it is perhaps superlatively uncompromising, whereas other abstracts fudge their credentials somewhat. It makes up for the omission of any real trace of abstract expressionism, the trump card of the next generation.

This show is the work of Barbara Jones, the museum’s curator, firmly supported by director Judith O’Toole. It could not come at a better time, and it is difficult to imagine how it could be bettered in the space available. For this, and for her continuing work at the museum, Jones at the opening dinner was awarded the Westmoreland Society’s Gold Medal, trimmed with green silk, her defining color and the ultimate chic.