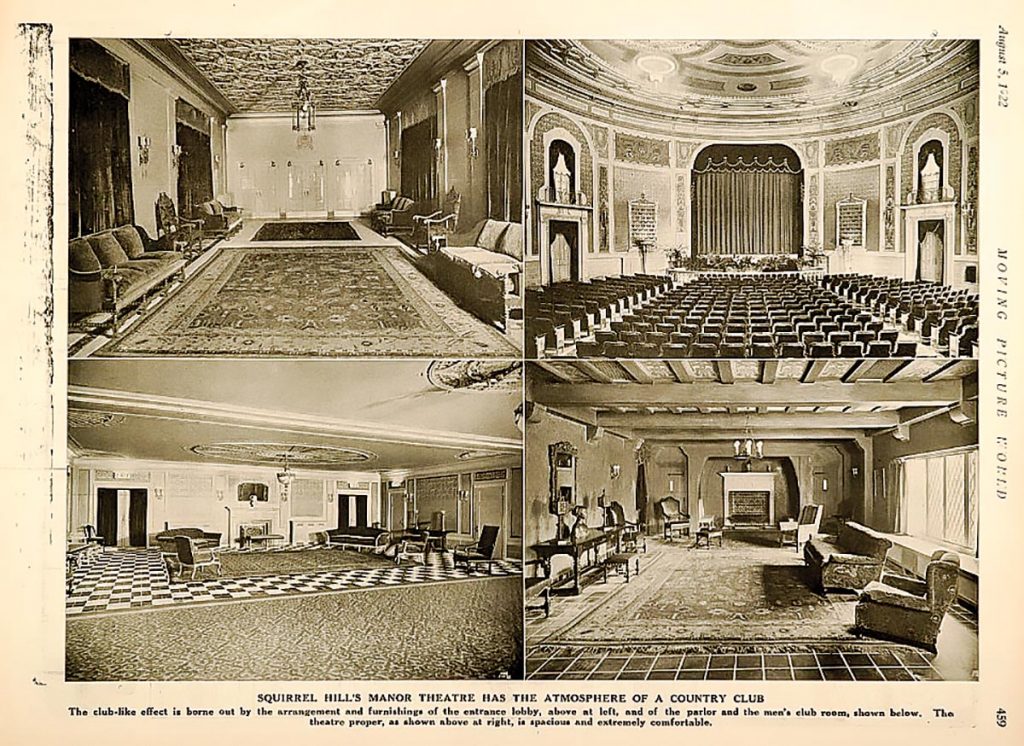

On opening night a century ago, velour drapes accentuated the auditorium doors and Juliet balconies. A newfangled ventilation system filtered smoke from a cigar lounge. And beneath an ornate plaster ceiling, Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce president Marcus Rauh dedicated the Manor Theater before a standing-room-only crowd of nearly 1,500.

Bookended by pandemics, the “photoplay” theater on the corner of Murray Avenue and Darlington Road has faced the spectrum of doomsday scenarios — megaplexes, VHS, DVD and streaming video — that have turned out the lights of sof many theaters like it. And for 100 years, it has survived and thrived.

Even before its “automated curtain machine” opened for the first time, art critics deemed the Manor to be one of the “most beautiful and harmoniously designed theaters” they had ever seen. According to The Pittsburgh Press, the Rowland & Clark theater group and architect Harry S. Blair were “responsible for giving to Squirrel Hill one of the country’s finest theaters.”

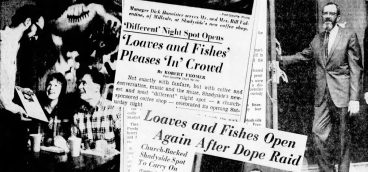

And since then the Manor has played host not only to films but also to local history. Jewish holiday services were common. So too were “Junior Commandos” collecting ashtrays for naval men during wartime, and “scrap matinees” offering free admission in exchange for five pounds of metal. After a long day in 1924, Rita Bennett triumphed over 1,036 competitors and was crowned “Perfect Baby” in the under-2 category. In 1929, Audrey Maxine Crone and Eleanor Lawrence survived multiple elimination rounds before moving on to represent the Manor as semi-finalists in the Warner Brothers “Miss Sunshine” pageant. And the theater appears to have been racially progressive as well, with owner Warner Brothers telling the Pittsburgh Courier in 1931 the company “always welcomed Negroes … and offer every courtesy and convenience to their patrons, according to race or color …”

Current Manor owner Rick Stern was in college when his father Ernest and his father’s cousin George sold the Manor and the rest of their Associated Theaters circuit to the Cinemette Corporation in 1974. When Cinemette ran into financial trouble in 1978, the Sterns bought the theaters back. After converting the Manor to a twin-screen, they sold the circuit again in 1987, this time to New York-based Cinema World. Soon after, rumors about the Manor’s demise circulated. Despite the financial backing of The Seagram Company’s Bronfman family, Cinema World’s then-president Jeffrey Lewine announced the Manor’s closing, and suggested that Rick Stern run it himself.

Revenues had fallen by a third after the multiplex Waterworks Cinemas opened in 1990. Two years later, Stern announced in the Post-Gazette that, “Everyone can count on that theater being renovated.” At that point, he owned the building but not the theater. But shortly after, he bought the business back again, also acquiring the nearby Squirrel Hill theater and two others. “I was clearly back in the theater business,” Stern recalled with a laugh. A $400,000 renovation doubled the screens to four, and the Manor’s doors stayed open every day for the next 28 years, until the COVID lockdown in 2020.

Effortlessly nestled into Squirrel Hill’s business district,

the Manor was one of the largest movie houses in

Pittsburgh.

The 1990s were good years, as the Manor and Squirrel Hill Theaters found ways to coexist with Waterworks. Then, in 2000, Loews (now AMC Waterfront) opened three miles away with luxury VIP seating, a sea of free parking and 22 screens. Combined, the two Squirrel Hill theaters had 10. “That impacted us much more dramatically,” Stern said. He closed the Squirrel Hill Theater soon after, but the competition helped the Manor solidify a niche audience drawn to independent films.

In 2012, new seats and concessions and a full-service bar became part of another major renovation, which included bringing back some past grandeur — restoring marble floors in the entryway, along with a plaster medallion above the main lobby.

The evolution to four screens has enabled the theater to respond to shifting customer demographics, especially during the pandemic. “Longtime customers love their foreign films and documentaries,” said general manager Tony Cammarata, noting, however, the three Hollywood films now showing. “Years ago it would have been the other way around.”

The pandemic has tilted demographics younger, toward adults under 35, and adding more blockbuster movies has helped the bottom line. “‘Spiderman’ was one of our busiest days,” said manager Geoff Sanderson, adding that “Black Panther” was the highest-grossing film during his decade at the Manor. Yet Sanderson says that smaller films such as “Grand Budapest Hotel” and “Silver Linings Playbook,” which ran for seven months, also have been very popular.

So what is the financial picture for the last Pittsburgh movie theater of its kind? Stern didn’t discuss specific dollar amounts, but said that, between 2012 and the pandemic, Manor revenues increased 5-10 percent annually. Revenue in 2018 and 2019 was strong, as was the end of 2021.

And it continues Pittsburgh’s historic role as the place that gave rise to the movies with the first nickelodeon in 1905, on Smithfield Street, Downtown. In 1908, Manor co-creator James B. Clark became president of a newly formed $8 million venture called the Moving Pictures Combine. Through it, the Post-Gazette wrote, Clark would “control the entire moving picture business of the world.” He sought to eliminate “the little nickelodeons scattered throughout the country where conditions are not fit for a woman to enter.” By 1915, Clark and his brother-in-law Richard A. Rowland formed the Metro Film Company, which they sold to Marcus Loew, who then acquired film companies Goldwyn and Mayer, forming MGM in 1924. A few years later, Loew began construction on the Loew’s and United Artists’ Penn Theater, now Heinz Hall for the Performing Arts.

Hosting pageants, war drives and religious services through the years,

the Manor was a hub for neighborhood civic life.

“Pittsburgh has figured most importantly in the growth and development of the film industry,” Rowland wrote in a 1941 Post-Gazette editorial. “I remember one day in 1907 when a man came to my office here from New Castle, Pa., for film to go into the theater business. This was Harry M. Warner, now president of Warner Brothers.”

The name Loews is all but gone (now AMC), and MGM soon will be too. Amazon purchased it last year for $8.45 billion. The Manor, however, the last of Rowland & Clark’s Pittsburgh movie theaters, remains. In its first year, back in 1922, the Manor showed “Hail the Woman,” a silent film that it showed again in May of 2022 as part of its centennial celebration — one of 10 films representing each decade of the Manor’s history, including “His Girl Friday” and a high-definition restoration of “The Godfather.”

“I always thought the Manor was a gem,” said Breonna DeVaughn, a young mother working the Manor ticket counter. DeVaughn has been working at the Manor for five months, but has been coming since she was a kid, mostly to see movies she couldn’t see other places. “It’s different. I think people come wanting to make new memories here.”

Mel Berkovitz also has been coming since he was a teenager. He’s in his 90s now, so he has a lot of memories. “My father was a Manor projectionist for Warner Brothers in the ’30s and ’40s. Celluloid film was highly flammable, so reels needed to be rewound by hand. He didn’t like rewinding film, so I came in after school to do it for him.” The Saturday matinee serials were some of Berkowitz’s favorites, especially “The Shadow.” He also recalls weekly raffles called “Bank Days,” where winning ticket holders would leave with an extra $10 or $20, but sometimes hundreds

.

For Dr. Cyril Wecht, the Manor recalls to mind the Rialto theater in the Lower Hill District where he grew up, but “in a more sophisticated, more comfortable fashion.” A Manor customer since his family moved to Squirrel Hill in 1951, Wecht likely sums up the thoughts of many with his description: “The Manor is a wonderful neighborhood theater.” pq

Jason Vrabel is freelance writer based in Pittsburgh.