Between Fear and Freedom

“Anish! Anish! Oi, Anish! Wake up!” Phurba Dai, our sardar—the expedition leader—shouted in his deep, commanding voice. “It’s already late! Haven’t you woken up yet?” Anish, our cook, was supposed to rise early to prepare hot tea and porridge and wake the rest of the team. But there he was, still fast asleep, curled up just outside our tent, oblivious to the passing time.

It was summit day, and our plan was to leave by 1 a.m., but exhaustion had taken over. Time had slipped away while we dozed off, unaware of the minutes ticking by. The biting cold at 8,000 meters froze the air, the ground, and seemingly, our motivation. We were in the death zone where the oxygen level was too low to sustain human life for long.

Phurba Dai’s voice snapped Anish into action. In a fluster, he began boiling water for tea. I, too, was reluctant to leave the thin warmth of my sleeping bag, having just fallen asleep around midnight. The frost clung to my gear and the tent walls. Even inside, the temperature was close to 13 degrees below zero, and every breath I took felt like inhaling shards of ice.

Despite the cold, I knew I had no choice but to move. Everyone around me was gulping down their tea, the steam rising in the frigid air, but my body ached for just a little more sleep. Still sluggish, I fumbled with my gear. By the time I was ready, it was already 1:45 a.m. — way behind schedule. My hands, stiff from the cold, trembled as I strapped on my boots. There was no time for tea or porridge; I grabbed my gear and hurried off, trailing behind the rest.

The night was unnervingly quiet. Only the crunch of snow under my boots and the occasional gust of wind broke the silence. My breath came hard and fast, loud inside my oxygen mask. That’s when I noticed something was wrong — no oxygen was flowing. My mask had frozen. Panic hit me hard, the biting air stinging my lungs as I fumbled with the mask, trying to fix it.

Finally, after what felt like an eternity, I managed to get the oxygen flowing again and resumed the climb, but the blackness of the night was disorienting. My headlamp cast a small, lonely pool of light, guiding me forward. After about an hour of slow, deliberate steps, I realized I was about 20 meters behind the group, the silence of the mountain pressing down on me.

Suddenly, my headlamp caught something up ahead — a figure, lying motionless in the snow. My heart stopped for a moment. As I moved closer, reality hit me hard: A body. Dead. Frozen in time.

Death is always this abstract concept until it’s right in front of you. Up here, it feels less like an ending and more like something waiting in the shadows, creeping closer with every step. For a moment, I froze, too, my legs refusing to move. What if that were me? What if my body ended up as just another landmark for future climbers to pass by?

I forced myself to keep walking, but the fear had set in deep. Every step felt heavier, as if I was dragging not just my body but my soul through the snow. The cold that had been numbing before now felt sharper, cutting through my layers, making me painfully aware of every breath. My heart raced, more from the terror than the altitude. Each step was a mental battle to keep going, to keep fear at bay.

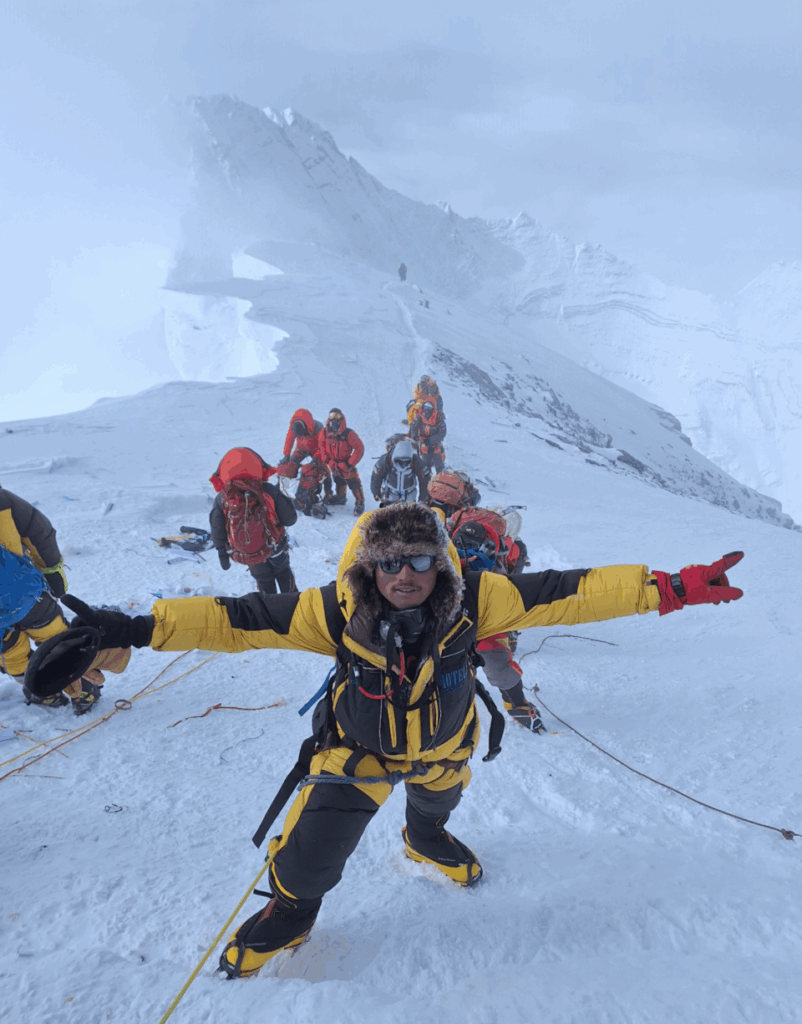

By the time I reached the Balcony — a narrow, exposed shelf at 8,400 meters — I was exhausted, but seeing other climbers was a relief. The wind slapped my face, biting into my skin. My breath formed frost on my eyelashes, and my oxygen mask was caked with ice. The mountain felt alive, breathing with the wind and the climbers.

As the first light of dawn broke, the mountains began to glow. The peaks were brushed with a deep red, like fire smoldering in the cold. And in that moment, the fear that had been gnawing at me slowly eased. There was a strange peace in the quiet chaos around me. The view was unreal — the vast expanse of the Himalayas stretching endlessly below, peaks shimmering in the morning light. It was beauty and brutality all at once, and it pulled me out of my exhaustion.

We were behind schedule but still moving fast. Other climbers struggled with every step, their bodies reaching their limits, but I found a rhythm, something steady that kept me moving forward. Along the way, I passed more bodies — five, in total. It felt unreal. But that’s Everest for you. The mountain doesn’t care about you. Life and death are equally insignificant here.

At 7:45 a.m., I reached the summit, after six hours of brutal climbing on a 25-day trek. The wind at the top of the world was merciless, cutting through my clothes, freezing every part of me. At 29,032 feet, I stood there, looking out over the world. But there was no triumphant rush, no overwhelming pride. Just stillness.

I stood there for 35 minutes, staring at the peaks and the clouds below, trying to make sense of it all. Why had I done this? What had I been looking for up here? Freedom? Peace? Did I find it? I didn’t have an answer then, and I’m not sure I have one now.

What I do know is this: Up here, at the highest point on Earth, everything else fades away. Your fears, your doubts, your pain — they’re still there, but they don’t control you. Maybe that’s the lesson. Life goes on, whether you’re standing at sea level or on top of the world. And so must we.