Most students in 19th century America walked to their local one-room schoolhouse to learn reading, writing and arithmetic in a classroom with a handful of other kids ranging in age and ability. With the youngest children seated at the front of the class, they memorized and recited their lessons. Once a mainstay of public education with 190,000 one-room schools operating in the U.S. in 1918, they all but disappeared by the late 1930s as the way America learned shifted to teaching students in larger, more formal consolidated schools segregated by grade level.

In 2020, the one-room schoolhouse concept made a comeback with “learning hubs” popping up as makeshift classrooms in YMCAs, Boys and Girls Clubs and other community-based settings as an emergency response to widespread school closings during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The hubs, which coordinated instruction with local school districts, organized small groups of students and teachers who were able to meet in-person and work together more intimately than the larger classes in their regular schools allowed.

“You had kids in mixed grades in the same room. It was going back to the one-room schoolhouse philosophy from the early days of schools,” said Lisa Abel-Palmieri, president and CEO of Boys & Girls Clubs of Western Pennsylvania, which operated seven learning hubs in Allegheny County during the 2020-2021 school year. “When we think of learning innovation, we think of kids having to be separated into different rooms in different grades. But for some kids, we’ve seen that not having those constraints improved their outcomes.”

Researchers consider learning hubs one of the bright spots for education during the pandemic and a possible model for broadening educational options in communities. But, just as the 19th century one-room schoolhouse disappeared, learning hubs are vanishing as funding to combat pandemic-related learning loss has shifted to school districts, which reopened in the fall.

NEED FOR A SAFE SPACE

COVID-19 dealt schools an immediate crisis when it swept it into southwestern Pennsylvania in March 2020. Schools closed and districts scrambled to piece together strategies to bring instruction to students remotely. Even six months later, when the 2020-2021 school year began, there wasn’t a uniform strategy for schools in the region or list of best practices to guide their response to the lingering pandemic.

Approaches varied among school districts, ranging from fully in-person instruction to fully remote instruction, all of which were subject to change if the public health crisis warranted. Remote learning, which before COVID was mostly limited to cyber charter schools, became a common characteristic of the pandemic response. Nearly 93 percent of families with school-age children in the U.S. reported receiving some form of remote or distance learning during the pandemic, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. Pittsburgh Public Schools, the region’s largest district, started and remained fully virtual for most of the school year.

But remote learning was not without problems. Some students lacked the devices and broadband access it required. And remote learning strained families who relied on schools as a safe place for their children while the adults were at work.

In many families, there wasn’t a parent or guardian available to become an instant teacher. An estimated 26 million U.S. workers with children 14 or younger don’t have in-home care options, according to a 2020 analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data by the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit think tank.

“I think we don’t like to think of K-12 schooling as fulfilling that child care need but it’s probably a good time to acknowledge that,” said Cara Ciminillo, executive director of Trying Together, a Pittsburgh educational nonprofit. “You have a lot of families that are essential workers. They work in the health care industry, the service industry; they’re mail carriers, bus drivers – they do all the things that are critical to our community continuing to function. And their young, school-age children need a safe place during the day.”

Nonprofits, churches, child care providers — groups with experience operating community-based learning programs, such as after-school programs — emerged as ready allies to help school districts confront the crisis.

A NEVER-ENDING SUMMER CAMP

In September 2020, the Allegheny County Department of Human Services, the United Way and Trying Together directed some of the pandemic relief funds received under the federal CARES Act dollars to local early child care and out-of-school time providers to try an educational experiment.

A network of 62 learning hubs was created to serve students during the 2020-2021 school year as part of a partnership between the county, Allegheny County Partners for Out-Of-School Time and Trying Together. The cost amounted to about $800,000 a month.

“In Pittsburgh there is a lot of collaboration and partnerships,” said Amy Malen, assistant deputy director at the county Department of Human Services.

“With this, we said let’s pool it together, let’s create a joint funding opportunity and make it as easy as possible to have providers have one place to go to seek funding. I don’t know if that’s something we would’ve thought to do if there hadn’t been this urgency.”

Churches, YMCAs, Boys & Girls Clubs, licensed child care providers and community centers stayed open past their typical hours. They functioned as pop-up classrooms — creating an environment for kids to do their schoolwork. Community learning hubs provided a safe place to learn and reliable WiFi for virtual classes. They provided lunches. Experienced child care providers and educators oversaw the students working in small groups as the kids beamed into their remote classes.

For many, it was as if “summer day camp never ended,” Abel-Palmieri said.

Across the country, more than 350 learning hubs operated during the 2020-2021 school year, according to the Center for Reinvention Education, an education research center, which created a database to track learning hubs.

In Allegheny County, the funding allowed out-of-school-time providers like Boys & Girls Clubs to hire additional staff and expand their hours — staying open for 13 hours a day last year.

Because their facilities, as well as many other learning hub providers, are licensed as child care buildings by the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, they are required to abide by strict staff-to-child ratios. As a result, the learning hubs had one staff member overseeing no more than 12 students — an instructor-student ratio much lower than that found in most public school classrooms.

“Learning pods are one of the key innovations that have come out of the pandemic, even though they were probably something that came out of the home-school space when people would gather,” said Temple Lovelace, founder and director of Assessment for Good, an education research organization and former director of special education at Duquesne University. “I really want learning pods to remain. I think that using the community as a resource is critically important.”

Learning hubs drew attention to how and where students learn and offered new partnership possibilities. “The pandemic shed light on a lot of inequities and inequalities that many of us already knew existed and this provided an opportunity to strengthen relationships between school districts and schools and communities,” said Valerie Kinloch, dean of the University of Pittsburgh School of Education. “It strengthened the relationship or should have strengthened the relationship between school districts and out-of-school-providers because at the core of this is ensuring that all students have the opportunity to thrive.”

They also served as a hub for interactions and communication between families and schools.

“There was really tight communication from across every level from superintendent, to principal to teachers,” Malen said. “Schools were really relying on learning hubs to be a safe physical space for kids and the learning hubs needed to rely on the schools to provide the educational content. I think that’s the biggest win.”

Early estimates of the impact the pandemic has had on students suggest an all-hands-on-deck approach will be needed to help them recover from more than a year of disrupted learning.

UNFINISHED LEARNING

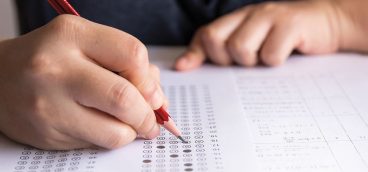

On average, K-12 students in the U.S. finished the 2020-2021 school year five months behind in mathematics and four months behind in reading, according to a 2021 study by McKinsey and Company.

Previous inequities in education persisted. Students in majority black schools finished six months behind in math, and students attending low-income schools ended the year seven months behind based on the previous year, according to the study.

But many education experts consider the term “learning loss” to be misleading. “I’m very concerned with the rhetoric of learning loss and the idea that there was a whole bunch of stuff that students were supposed to learn, but didn’t,” said Justin Reich, director of the Teaching Systems Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“It would be a huge mistake to describe the kids when they come back in the fall as learning losers — if you were behind before, you’re really behind now. Instead, the place to start is to recognize that you can’t stop students from learning — they’ve been learning all year. They may not have been learning the things we set out for them to learn, but they’re learning all kinds of things and we should celebrate what they have accomplished and extend the learning from there.”

Another way to look at learning loss is the need for teachers to challenge students with grade-level content and figure out which specific areas of knowledge a student has yet to master. It’s referred to as “unfinished learning” and is seen as a starting point for addressing the disruptions students experienced during the pandemic.

For many students, the interruption to their school day also affected their social and emotional well-being. About 30 percent of U.S. parents surveyed said their children were experiencing harm to their emotional or mental health, according to a 2020 Gallup poll. And 45 percent felt the isolation from teachers and classmates was a “major challenge.”

But the pandemic also forced educators and policymakers to explore new approaches and rethink strategies for educating children. “What does it look like to teach in person?” Kinloch said. “What does it mean to teach remotely? Why are we putting these two structures at odds with one another? We shouldn’t. If we could provide equipment to enable remote learning, why would we take it away? Why couldn’t we keep those structures we put in place and build on those structures to reimagine public education?”

UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Recent changes in pandemic relief funding make it unlikely the learning hubs that flourished during the pandemic’s darkest days will continue to play such a key role in the education of students.

Funding for Allegheny County’s network of learning hubs had dried up by the start of the 2021-2022 school year this fall.

More federal pandemic relief dollars are flowing into states, counties and cities under the American Rescue Plan, which required them to spend 20 percent of them to address learning loss. But in Pennsylvania, those funds now go directly to school districts.

And it’s unclear what the future holds for the partnerships school districts formed with the out-of-school-time community organizations that operated learning hubs when schools, students and parents needed them the most.

“The biggest worry is that now funding is gone, connections will be gone because learning isn’t happening in our buildings anymore through school districts,” Abel-Palmieri said. “If that just goes away like a light switch, what happens to the gains we’ve made? We have some families saying, ‘I never want my kid going back to their school building.’ They ask: Can they just come here and you can run cyber school?”

The brief era of learning hubs may be over, but their presence in the community during a global pandemic sparked the possibility of expanding a formal system of education beyond a school building. As Abel-Palmieri said, “This idea of out-of-school life and in-school life coming together is the perfect connected learning environment.”