A Victim of the Life He Led

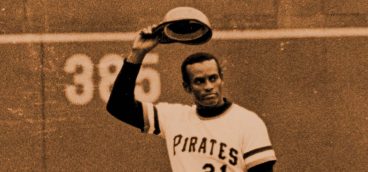

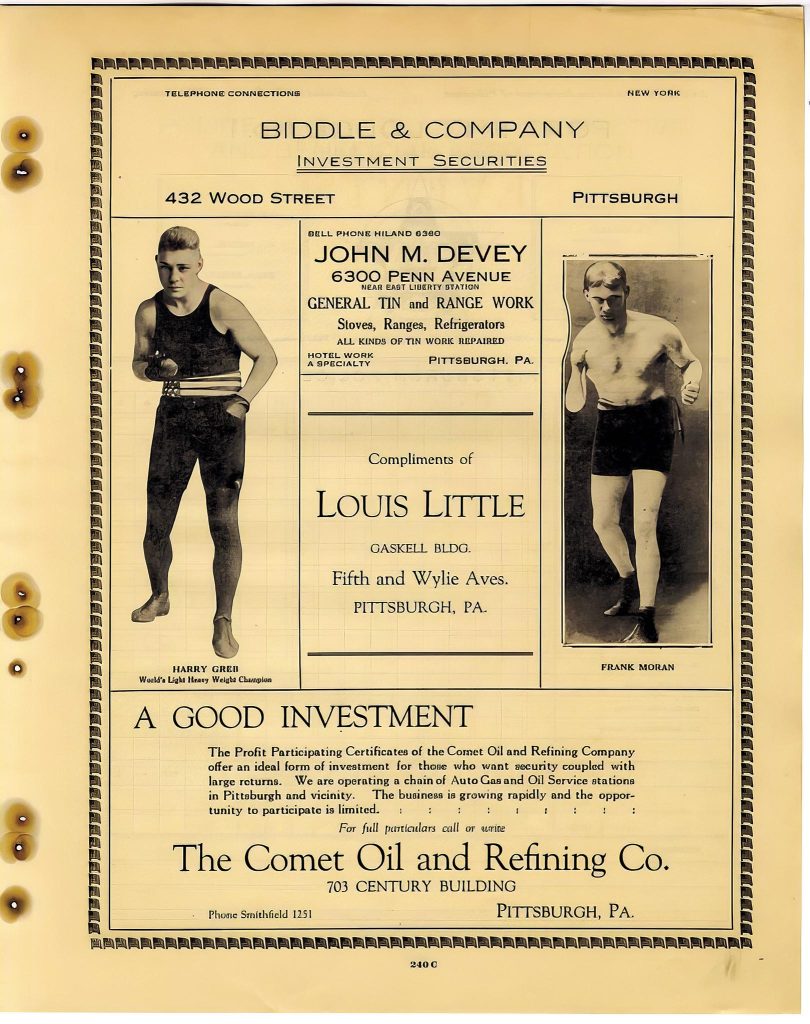

Pittsburgh is unquestionably one of the great fighting cities in the United States. The city and its surrounding boroughs have produced world champions Billy Conn, Michael Moorer, Paul Spadafora, and a whole host of other world-class pugilists. Experts in the fight business place two-time world champion Harry Greb on top of Pittsburgh’s pugilistic slag pile. They regard the former middleweight and light-heavyweight champion as one of the most accomplished fighters in boxing history.

In 1955, The Ring magazine, the Bible of boxing, elected Greb to its Hall of Fame and the International Boxing Hall of Fame (IBHOF) in Canastota, N.Y., inducted him in 1990. In an end-of-the century retrospective issue, The Ring ranked Greb as the greatest middleweight of all time. That same issue called Greb the second-greatest pound-for-pound fighter ever, behind Sugar Ray Robinson.

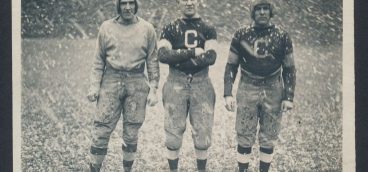

Greb defeated a total of 12 future middleweight, light-heavyweight, and heavyweight champions, an illustrious group that includes 11 inductees of the IBHOF. Most notably, the natural middleweight Greb, who fought at around 160 pounds, defeated 175-pound light-heavyweight champion Gene Tunney to take his title in 1922. Greb was the only fighter in 89 professional bouts to ever defeat “The Fighting Marine,” who went on to beat Jack Dempsey for the heavyweight title in 1926.

Greb was also one of the most prolific fighters of all time. Between 1913 and 1926, he fought at least 300 times professionally, taking on as many as 37 bouts in a single year.

Nicknamed the “Pittsburgh Windmill,” Greb earned the moniker with his confrontational, free-swinging punching style. He blitzed opponents of all sizes with a flurry of inside punches that resembled the chugging of a locomotive. The little remaining footage of Greb’s fights shows him to have been a dynamo of perpetual motion when he swung his fists. In an era characterized by slim fighters in all weight classes, Greb’s physique stood out. He looked like a Greek god with his bulging biceps, tight stomach, and pronounced trapezius.

***

Edward Henry Greb was born on June 6, 1894, near his family’s home in Pittsburgh’s East End. He was the son of German immigrants Pious and Anna Greb, parishioners at St. Philomena’s, then the German Catholic parish in Squirrel Hill. It is unlikely that very many other Catholic parishes can boast two boxing world champions. Like Harry Greb, light-heavyweight champion Billy Conn was raised in St. Philomena Parish.

Twenty-year-old Pious emigrated from Germany in 1880 and settled in Pittsburgh’s vibrant German community. In 1892, he married a fellow German immigrant named Anna Wilbert. Pious made a steady living as a stone mason and the family settled into a home at 138 N. Millvale Ave. in the Garfield neighborhood. The Grebs had six children, including a little boy who died as a baby and a girl, Lillian, who died as a teenager. Harry was the oldest boy and had four sisters. Ida, who was just two years younger, remained the closest to Harry throughout his life.

For many years, a myth persisted that Harry Greb’s last name originally had been “Berg” and that he started spelling the name backwards because he thought it sounded “too Jewish.” Decades after his death, a sportswriter found Greb’s birth certificate, which showed the family name was, in fact, “Greb.” The Berg/Greb story never rang true anyway. Greb did not display prejudice and proved himself to be a strikingly open-minded person for his era.

Young Harry Greb was known to be a lover and a fighter, a reputation he retained for the rest of his life. Friends and family remembered him as simultaneously pugnacious and affectionate, willing to scrap with much bigger kids in their East End neighborhood while also carrying home the books of whichever girl caught his fancy that afternoon.

He learned to box in the numerous gyms and athletic clubs of Pittsburgh as a teenager, soon proving to be an apt pupil of several local trainers. Sixteen-year-old Greb started working at Westinghouse’s East End plant as an electrician’s assistant before turning to boxing full time.

He turned professional in 1913 and made an immediate mark on the local boxing scene, finishing the year 7-2-1. In late November, he suffered the only knockout of his career and rebounded by going undefeated in his next 18 fights. For the next four years, Greb plied his trade primarily in Pittsburgh, losing just nine of his 104 prize fights by the end of 1917. It took the promotional guile of one of Pittsburgh’s best fight promoters to get Greb noticed beyond Western Pennsylvania.

The young middleweight moved beyond Pittsburgh’s athletic clubs because of his leather-lunged manager, James “Red” Mason. A tireless advocate for his fighters, Mason used his bravado and connections to the East Coast fighting establishment to get Greb the kind of bouts that made him a championship contender.

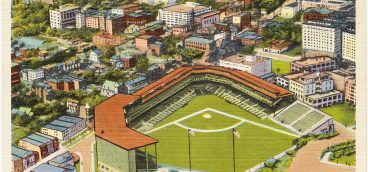

Over the next few years, Greb toiled his way to the top, defeating several former champions before finally getting a world title shot in 1922. His push for the title was nearly derailed in 1921 during a bout with Kid Norfolk. Early in the fight at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, Norfolk gouged Greb’s eye, detaching the retina in Greb’s right eye and rendering him blind in that eye for the rest of his life. Few beyond Greb’s immediate family and personal doctor knew of the severity of the injury. Beyond its impact on his vision, Greb’s right eye was painful, subject to disease, and frequently infected. For the next five years, he went toe-to-toe with some of the world’s most dangerous men with severely impaired vision.

Greb didn’t get a shot in his typical middleweight division, but instead a shot at Gene Tunney’s light-heavyweight title. On May 23, 1922, the 13,000-plus fans assembled at New York’s Madison Square Garden witnessed Greb lay a horrific beating on the taller and heavier hometown hero. Seconds into the fight, Greb busted the champ’s nose and spent the rest of the evening fighting close to Tunney’s body, turning his face into a “bloody ruin” and “hamburger,” according to United Press reports. Greb won the belt on a unanimous decision and Tunney spent the night in the hospital, as doctors worked to repair his battered visage.

Tunney would regain his light-heavyweight title against Greb the following year by split decision and the pair would fight a total of five times. Over the course of their rivalry, Tunney and Greb became close friends. The future heavyweight champion later cited Greb’s encouragement and guidance as a significant aspect of his preparation for fighting Dempsey.

After Greb dislodged light-heavyweight champion Tunney, sportswriters wondered if Greb could move up and beat heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey himself. Greb had, in fact, done just that in a private bout. While Dempsey trained for his December 1920 title defense against Bill Brennan, the champ brought in Greb as a sparring partner. After two rounds of vicious body blows from Greb, Dempsey called the whole thing off. Publicly, Greb said he thought he could beat Dempsey for the title but never got his shot. Instead, Tunney got the chance and took Dempsey’s belt.

Despite sportswriters’ admiration for Greb’s skills, the “Pittsburgh Windmill” took a beating in the press throughout his career. Critics called him cocksure and uncommitted to the rigors of training. They chastised his apparent taste for strong drink, the night life, and alleged womanizing. Greb was also something of a dandy, known to flaunt his new wealth with the bespoke clothing and flashy jewelry he sported in public. Footage of Greb’s training says otherwise, showing off an athlete who engaged in rigorous calisthenics, sparring, and abdominal exercises.

“Harry Greb’s methods of training are said to be confined entirely to a shave and a massage before the match,” Pulitzer Prize-winning Atlanta Constitution editor Ralph McGill wrote in 1926 while a young sportswriter for the Nashville Banner. “Harry Greb is becoming a menace to those who teach moral lessons about training and observing rules,” McGill concluded.

While much of the press pilloried Greb for his apparently outlandish lifestyle, he found allies in the era’s vibrant black press, including his hometown Pittsburgh Courier. While many champions, including Jack Dempsey, did not take on black challengers during that era, Greb fought a number of black opponents, including Tiger Flowers, who later took his middleweight title.

For all of the hullabaloo, it turned out that Harry Greb was a committed family man. He married his childhood sweetheart, Mildred Reilly, in 1917. The couple had their only child, a daughter named Dorothy, two years later. Mildred suffered from tuberculosis and her health deteriorated rapidly in the years after Dorothy’s birth.

In early 1922, Mildred, Dorothy, and Harry headed for Saranac Lake, N.Y., then the gold standard for TB-care with its fresh Adirondack Mountain air and village of “cure cottages.” Greb prepared for his first Tunney fight in the Adirondacks to remain close to his wife and daughter. A photograph of Mildred listening to the title fight on the radio appeared in many papers across the country.

Late in the year, Mildred returned permanently to Pittsburgh, with her condition only worsening. Back among her circle of friends and family, Mildred died in March 1923, several months shy of her 23rd birthday. Harry’s sister Ida and her husband Elmer Edwards helped raise Dorothy while her father continued his boxing career.

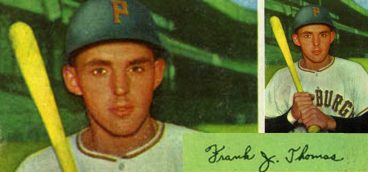

Greb won his middleweight title on Aug. 31, 1923, pummeling champion Johnny Wilson for 15 rounds at New York’s Polo Grounds to earn a unanimous decision victory. Over the next three years, Greb continued to fight frequently, continuing his rivalry with Tunney while defending his middleweight title successfully on six occasions. In February 1926, Greb lost his title in a controversial split decision against Tiger Flowers at Madison Square Garden. Six months later, Greb lost a similarly divisive split decision in the rematch, which proved to be his final fight. He announced his retirement from the ring and planned to open a boxing gym of his own in Pittsburgh.

Tragically, Greb was just weeks away from his death, which was brought on by injuries he sustained both in the ring and on the roadway.

In August 1925, Greb had suffered significant facial injuries in a car crash in Erie, compounding the injuries he already had suffered in the ring.

Just a couple of weeks after his final fight in August 1926, Greb had his right eye removed and replaced with a glass eye. His doctor feared that the trouble with his right eye would soon spread to his left, leaving him permanently blind.

In early October 1926, Greb had another serious auto accident, slamming his car into an embankment in Pittsburgh. He suffered a severely broken nose and had persistent headaches after the crash. On Oct. 21, 1926, Greb underwent reconstructive nasal surgery on the advice of his personal doctor; he was having significant trouble breathing through his nose. After attending his daughter’s seventh birthday party in Pittsburgh, Greb traveled with his fiancée, Naomi Braden, to Atlantic City to undergo the procedure.

Apparently, the movement of the bones in Greb’s nose and skull ruptured a blood clot in his brain. He suffered a brain hemorrhage and never regained consciousness. Just 32 years old, Greb was declared dead the next morning.

“Greb died in a sanitarium here Friday, a victim of the life he led,” a United Press report from Atlantic City intoned with striking callousness, noting that the surgery occurred in the first place because his nose had been “flattened in his most recent automobile smashup.”

The family held a public viewing of Harry’s body at Ida’s home at 1130 Jancey St. near Highland Park. Thousands of mourners passed through the Edwards family’s front room to pay their respects to the “Pittsburgh Windmill.” Similarly large crowds honored Greb outside St. Philomena’s during his funeral and followed the cortege down to Calvary Cemetery, where he was buried alongside his bride, Mildred. Dorothy remained in the Pittsburgh area for the rest of her life and raised a family, and Naomi married a businessman and settled in Florida.

It wasn’t until after his death that Greb’s sister Ida revealed his blindness to the public, almost immediately softening some of the ire slung his way by the era’s sporting press. It didn’t take the sports press long to realize how much they’d missed in the story of Harry Greb. Overnight, Greb became a legend of the ring — forever young, never forgotten by those that saw him, and permanently part of his hometown and his sport’s story.