Chanterelles

February 8, 2024

We bought a small section of woods some years ago that came with treasures not spelled out in the purchase agreement: chanterelles. We had no idea the prized orange mushroom would fruit the following summer. I wasn’t even positive what type of mushroom it was — I’d never foraged for chanterelles before — but after consulting my field guide, I was pretty positive they were chanterelles.

(Regarding mushroom identification, my husband balks at the words “pretty positive.”)

I admit I’m an amateur, despite the fact that I’ve been teaching myself about mushrooms since we moved to the farm 35 years ago. I’ve read enough to know that I never touch, no less pick and eat — barely inhale the air surrounding — a white, gilled mushroom. (It could be the deadly amanita.) I’ve identified puffballs, scarlet cup, chicken of the woods, stinkhorn, turkey tail, and many other types of mushrooms — and I’ve eaten countless pieces of buttery toast slathered with sautéed morels, for which I foraged. So, I’d say I’m fairly confident foraging for morels.

(Regarding mushroom identification, my husband balks at the words “fairly confident.”)

Ok, I am confident about morels.

Foraging for morels is far more challenging than chanterelles, however, for one basic reason: Chanterelles fruit in basically the same spot every year, whereas morels do not. Too much or too little rain might change the timing of chanterelle fruiting, but not the location. My field guide states that chanterelles fruit from July to September, which is when I’ve found them here, and describes them as “orange to yellow,” which is true of ours: some yellower, others more orange. The book claims chanterelles are found “especially along paths.” Spot on! Too easy!

I’ve since found chanterelles all over the farm.

Once I established that the newly discovered mushrooms were chanterelles, I set out to identify the species. I guessed they were smooth chanterelles — Cantharellus lateritius — but I wasn’t sure, so I asked a chanterelle expert, Rachel Swenie, Ph.D, of the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. She said identifying chanterelles can be tricky. “There are many species that look similar and within one species there can be a lot of variability,” she said. From a photo I sent her, she said we had Cantharellus flavolateritius, so I was half right: It was a smooth chanterelle, but flavolateritius, not lateritius, as the latter appears only in the Gulf Coast region of the U.S. Half right, unfortunately, should never be good enough in anyone’s book regarding mushroom identification.

When identifying mushrooms, Swenie considers where the mushroom was collected and which trees were nearby. (I have found beautiful specimens in an oak grove.) She uses scientific methods that a layperson may not, such as measuring spore size under a microscope and conducting DNA sequencing. “It’s like sleuthing,” she said. “You take all the information and at the end see if it helps. It’s rather difficult and takes a practiced eye.”

Doing such tests enabled her to identify a European species of chanterelle previously unknown in North America. The mushroom was sent to her by a citizen scientist in Connecticut and it turned out to be an albino version of Cantharellus cibarius. “It was a very neat find,” she said. “Earlier research had suggested all chanterelle species found in North America were unique to this continent, and that Cantharellus cibarius was a strictly European species.”

Chanterelles are ectomycorrhizal, meaning they form a symbiotic relationship with certain trees, such as oak, birch, beech, pine, fir, hemlock, and spruce. The mushroom is beneficial to the tree and the tree to the mushroom. “Chanterelles increase the surface area of the tree’s root system underground and scavenge minerals in the soil, nutrients that the trees would have difficulty accessing, such as nitrogen and phosphorus,” she explained. “The fungus transfers those nutrients to the tree and, in exchange, the tree sends some of the sugars it produces by photosynthesis to feed the fungus.”

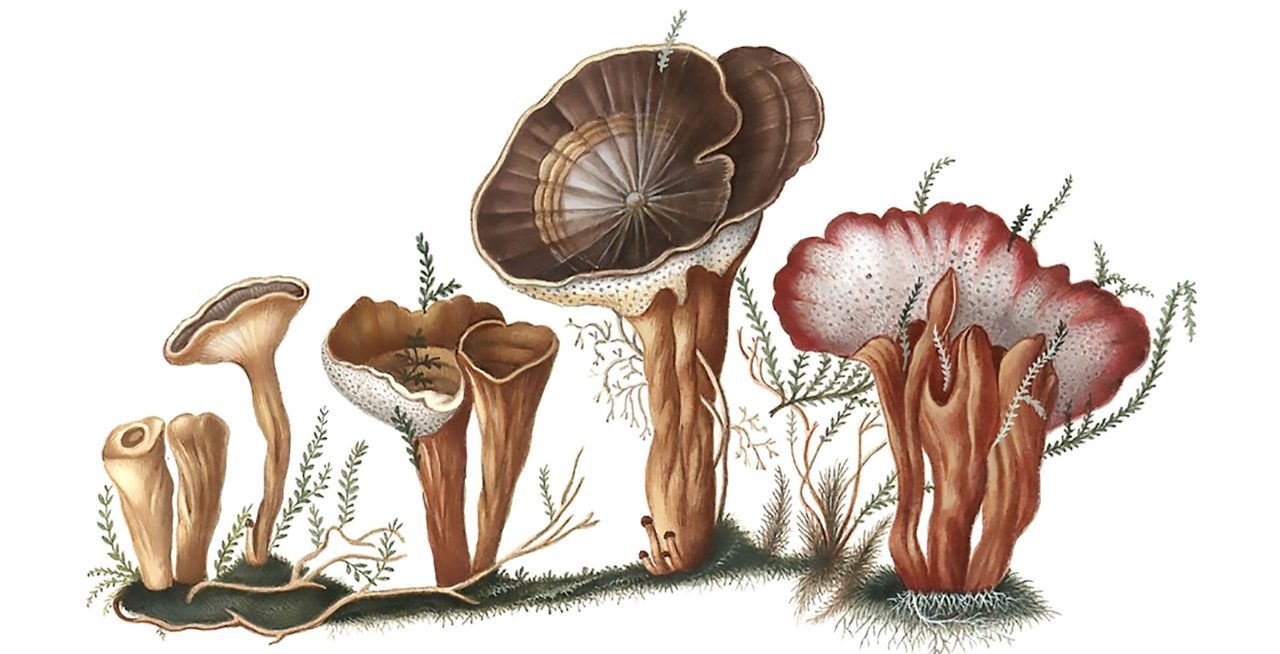

An unusual feature of the chanterelle is that it does not have true gills as most mushrooms do. Instead, it has wrinkles, or “gill-like folds,” Swenie called them. “You can rub the wrinkles off like clay,” she said. True gills cannot be rubbed off.

Numerous mushrooms can be confused with chanterelles. The most common look-alike in our area is the poisonous Jack-O-Lantern mushroom. One key difference between the two, explained John Plischke, a mycologist and founding member of the Western Pennsylvania Mushroom Club, is that Jack-O-Lanterns grow on wood, not on the ground. Still, that can be confusing. “If the wood rots and grows underground, you might see grass instead of wood,” he said. Another difference is that Jack-O-Lanterns grow in large clumps. “A dozen or so caps together,” Plischke said. “One or two chanterelles might grow together, but not a big clump.” Jack-O-Lanterns also have real gills.

Jack-O-Lanterns are bright orange like chanterelles, which may be the reason the two are often confused. But, Swenie said to be wary of using color when identifying any mushroom, because color can vary depending on when the mushroom is picked. “A lot of stuff changes color with age and rain,” she said.

Some foragers claim that chanterelles smell like apricots. I’ve smelled them — and I have a keen sense of smell — but I’ve never smelled apricots. “I don’t smell apricots either,” Plischke said. “Maybe a little fruity, or pleasant,” he said, but no apricots. Swenie pointed out that older and waterlogged mushrooms might also smell different. “Smell is not necessarily a tell-tale sign,” she said.

Other look-alikes include the “the false chanterelle,” Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca, and the shaggy, scaly, or wooly chanterelle, Turbinellus floccosus. “None of these are closely related to one another, nor to chanterelles,” Swenie said. “They just appear similar to chanterelles to the untrained eye.” The only group closely related to chanterelles that may be mistaken for them are trumpets mushrooms, in the genus Craterellus — “sisters to chanterelles,” Swenie called them. They are edible but are hollow down the middle, whereas “the interior of an edible chanterelle will be white and stringy, like string cheese,” she said.

“Really, the best way to learn to distinguish each of these groups is to learn from someone who knows them,” Swenie said. “Joining a local mycology club is often the best way to get this type of experience.”

How to wash mushrooms is a topic that splits people into two groups: those who wash them in water and those who believe water dilutes the taste. Swenie recommends cleaning them with a soft brush, but she isn’t against a quick swish with water. Just don’t waterlog them. “I have done both and personally do not see much of a difference,” she said. “It just depends on how tolerant one is of a little dirt. If the mushrooms are fresh, they will taste good either way.”

Chanterelles should be stored in wax paper or a brown paper bag in the refrigerator, she said. “Either of these options allow for gas exchange, unlike a plastic bag or plastic wrap, which will encourage bacterial growth and spoilage.” Instead of dehydrating chanterelles, she recommends sautéing and freezing them. “However, I have seen folks who swear by dehydrated and ground chanterelle powder for cooking, so again there is some personal preference here.”

Mushrooms are much in the news now with books such as Martin Sheldrake’s Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures and Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees. The much-used term, “the wood-wide web” which describes how mushrooms communicate with trees through the mycelium, has been attributed to Suzanne Simard’s work described in her book, Finding the Mother Tree. A great film about mushrooms is “Fantastic Fungi.” Still, despite all the interest in mushrooms, Swenie said that only 3 to 8 percent of the fungi in the world is currently described. “There are very few mycologists relative to other types of disciplines. Very few people take up that challenge. It’s a wide-open field.” Even amateurs have found new species. “There’s a lot of opportunity,” she said.

I asked Swenie for the definitive book on chanterelles and she said one doesn’t exist. “The science has been changing so much that the literature hasn’t kept up.” But she and some fellow mycologists are working on a book about the mushrooms of the southern Appalachians. When it’s published, I’ll buy it.

Then I will be utterly positive about my mushroom identification.