Bill Virdon: He Made Everything Look Easy

In the spring of 1956, I was a senior at Pittsburgh’s South High and the starting center fielder for the school baseball team.

For aspiring high school center fielders, the decade of the 1950s was a great time to be playing baseball and dreaming of a big league career. In the National League, there were three center fielders, Willie Mays, Duke Snider, and Richie Ashburn headed for the Hall of Fame. Over in the American League, there were future Hall-of-Famers Mickey Mantle and Larry Doby.

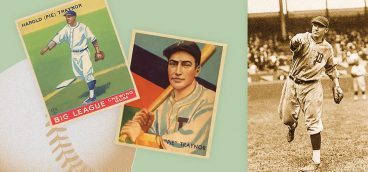

My idol, however, going into the 1956 season, was Pirates center fielder Bobby Del Greco, a Pittsburgh native who grew up and played baseball in the Hill District, just across the river from my working-class South Side. On the recommendation of Pie Traynor, Pirates general manager Branch Rickey had signed Del Greco as a teenager, and, by the 1952 season, at the age of nineteen, Del Greco was playing center field at Forbes Field.

The 1952 season was a disaster for both the Pirates and Del Greco. While the Pirates finished the season with a 42-112 season, the worst in the team’s modern history, Del Greco, in 99 games, hit an anemic .217 with one home run and 20 RBIs. After spending the next three years in the minor leagues, he returned to the Pirates in 1956. While, once again, he struggled at the bat, he played a brilliant center field, especially at a mammoth Forbes Field.

On May 13, 1956, I was sitting in the left-field bleachers at Forbes Field for a Sunday doubleheader against the Philadelphia Phillies. In the first game, Del Greco, who was hitting under .200, broke out of his hitting slump and launched two towering home runs over the 406 mark in left-center field to lead the Pirates to a 11-9 victory over the Phillies.

I was thrilled with the home runs, but so was St. Louis Cardinals general manager Frank Lane, who was at Forbes Field that Sunday to look into the prospect of making a trade with the Phillies or the Pirates. Lane had made so many trades in his career that he was known around the major leagues as Trader Lane.

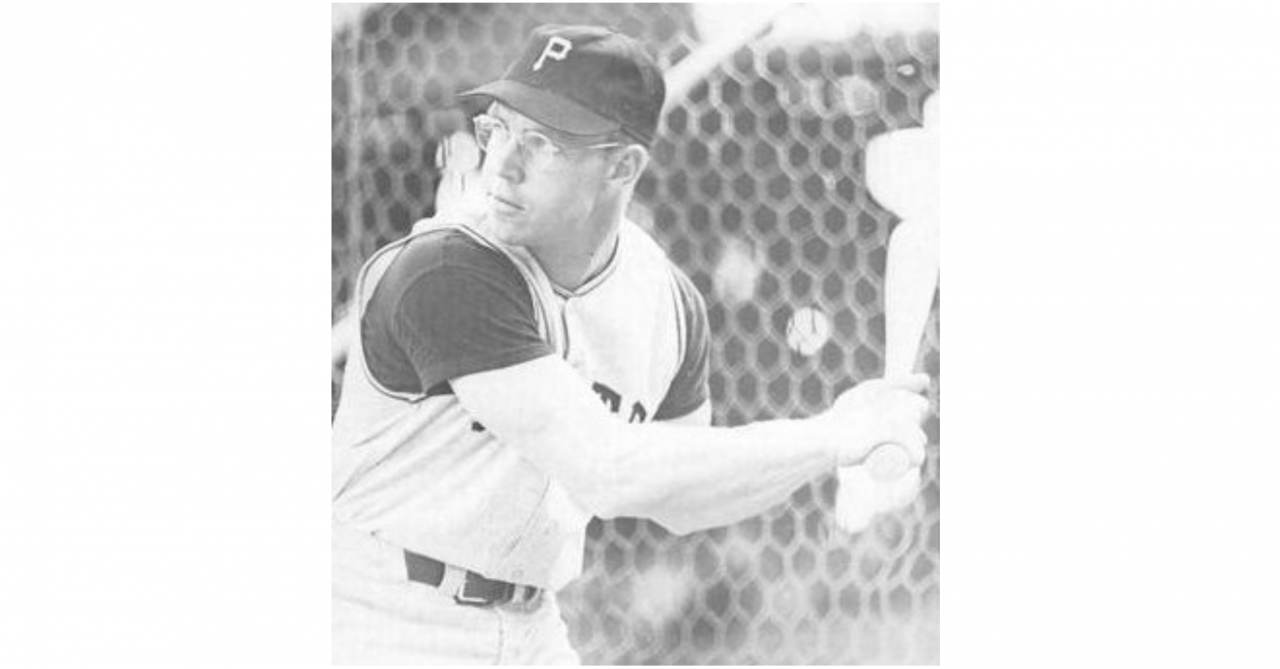

The Cardinals already had a young center fielder in Bill Virdon, who in his first season was named the 1955 National League Rookie of the Year. Virdon, however, wore glasses and was off to a slow start in 1956. Fearing that Virdon’s eyesight was failing, Lane offered Virdon to the Pirates for Del Greco, an offer that Joe L. Brown, who had replaced Rickey as general manager, quickly accepted and threw in pitcher Dick Littlefield in the bargain.

Trader Lane wasn’t done. That summer he proposed offering Donora native and Cardinal legend Stan Musial to the Phillies for their ace pitcher Robin Roberts, a deal that was vetoed by Cardinals owner Gussie Busch. Undaunted, Lane traded another Cardinal favorite, Red Schoendienst to the New York Giants, a deal that shocked Cardinal fans and infuriated Musial, Schoendienst’s best friend. A year later, Lane was out of a job.

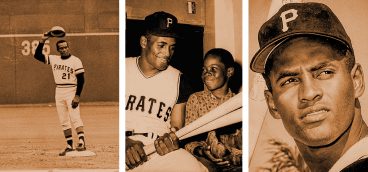

As for that Virdon-Del Greco trade, it worked out for the Pirates, but not for the Cardinals. While DelGreco continued to struggle at the plate and was traded to the Cubs less than a year later, Virdon hit .334 for the Pirates in 1956 and finished a combined .319, second best in the National League behind Hank Aaron. He also seemed to have a steadying influence on Robert Clemente, who struggled in 1955, his rookie season, but hit .311 in 1956, good for third best in the National League, just a point ahead of Musial.

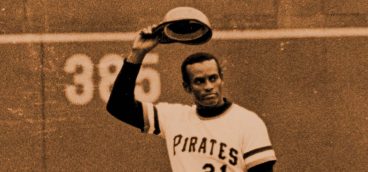

Virdon was a gift to the Pirates, but he also was a gift to a skinny center fielder from the South Side. While Virdon wasn’t a natural, like Willie Mays, he played the game with intelligence and grace. Clemente, who played alongside Virdon for a decade, said that “Virdon made everything look easy.”

Watching Virdon, I learned the value of quickness and timing, of getting a jump on the ball, of taking the right angle into the outfield gap, and waiting for the exact moment to reach out to make the catch. I also learned to slide under a ball hit in front of me instead of attempting a diving catch. Not only was it safer, it put me a position to pop up and make a quick throw back into the infield.

Though Bill Virdon didn’t have the power of Mantle and never hit over .300 after his first season with the Pirates, he was so skilled at looping the ball over the infield that Bob Prince called him the Quail because his hits resembled dying quails. He had such a knack for getting on base that his manager Danny Murtaugh had him leading off in front of Dick Groat.

A left-handed batter, Virdon never hit many home runs at Forbes Field with its high screen protecting the right field stands, but he was capable of driving balls into the Forbes Field’s wide outfield gaps. He hit more triples than home runs in his years with the Pirates and often finished in the National League’s top ten. In 1962, the same year he won a Gold Glove, he led the National League in triples.

Virdon’s most memorable hit came in the bottom of the eighth inning of the seventh game of the 1960 World Series when his ground ball took a bad hop and struck Yankees shortstop Tony Kubek in the throat. Instead of a double play, Virdon’s bad-hop hit set up the rally that culminated in Hal Smith’s three-run homer to give the Pirates a 9-7 lead.

Bill Mazeroski became the hero of the 1960 World Series when he hit his dramatic home run in the bottom of the ninth after the Yankees had tied the score, but Virdon, with his fielding, running, and hitting, was the most consistent Pirate in the clutch during the entire series.

In Game One, Virdon scored the Pirates first run after he walked, stole second, took third on an errant throw, and came home on Dick Groat’s double. In the top of the fourth, with the Pirates leading 3-1, the Yankees had two men on with only one out when Yogi Berra hit a deep drive to right-center field that Virdon tracked down and made a leaping catch at the wall, while barely avoiding a collision with Clemente. Instead of tying the score the Yankees scored only one run in the inning.

In the bottom of the fourth, Mazeroski’s two-run homer gave the Pirates a 5-2 lead. Two innings later, Virdon’s double off the right-field screen scored Mazeroski on the way to a 6-4 Pirates win.

In the Pirates critical 3-2 victory in the fourth game that tied the1960 World Series at two wins apiece, Virdon saved the Pirates with his bat and his glove. Trailing 1-0 in the top of the fifth, the Pirates tied the game on a Vern Law single and took a 3-1 lead on Virdon’s clutch two-out base hit. In the bottom of the seventh, the Yankees rallied and trailed the Pirates 3-2 with runners on first and second with only one out. When Bob Cerv lined a ball deep into the right-center gap, it looked like the Yankees would take a 4-3 lead until Virdon made a sensational sliding catch at the base of the wall. The Pirates held on for a 3-2 victory and tied the series on their way to their dramatic World Series victory.

Looking back on the 1960 World Series, Pirates pitcher Bob Friend said “Virdon hurt the Yankees.” Virdon had seven hits behind only Mazeroski, with eight, and Clemente, with nine. He tied Mazeroski with five RBIs and had three extra base hits, only one less than Mazeroski. But more than his clutch hitting, Virdon’s sensational catches saved two critical Pirate victories and kept the Pirates from being swept by the Yankees. Before Mazeroski’s home run, Virdon may well have been the Pirates‘ most valuable player.

Virdon and Clemente played beside each other from 1956 until Virdon was released and retired in 1965, but that wasn’t the end of their relationship. In 1968, the Pirates brought Virdon back as a coach. He was a Pirates coach when Clemente led the Pirates to the 1971 World Series championship, and, in 1972, after Danny Murtaugh retired, became the Pirates, manager in what became Clemente’s last season.

In 1972, Virdon led the Pirates to an easy division win. His Pirates were leading the Reds 3-2 and were three outs away from a National League pennant and a return trip to the World Series when a Johnny Bench home run and a wild pitch cost them the game and the pennant. Less than three months later, on New Years Eve, Roberto Clemente died in a plane crash.

When the Pirates struggled in 1973, they decided, late in the season to replace Virdon with Danny Murtaugh, but the Pirates still fell short of the playoffs. Virdon was hired in 1974 by the Yankees and went on to win The Sporting News American League Manager of the Year award. In 1980, he managed the Houston Astros to their first playoff appearance and won The Sporting News National League Manager of the Year award.

After his years of managing, Virdon returned to the Pirates as a coach and gave Pirate fans one more memorable moment. In 1991, at the Pirates spring training camp, the 69-year-old Virdon was conducting an outfield drill when he was confronted by Barry Bonds. Virdon, who had a reputation for toughness, didn’t back down, and when Jim Leyland heard the argument, he ran into the outfield and told Bonds to get off the field. He told reporters, Bonds “is not going to run this camp. He can just go home.”

On November 23, Bill Virdon died at the age of 90. With the approaching 50th anniversary of Clemente’s tragic death, there will be much written about arguably the greatest player in Pirates history, but it’s also an appropriate time, as the first anniversary of Virdon’s death approaches, to remember the player, who, as a teammate, coach, and manager, was so much a part of Clemente’s career and played such an important role in Pirates history.

While he wasn’t among the 19 Pirates selected as the first inductees for the Pirates Hall of Fame, he should be a strong candidate in the years ahead.