Whatever contributions Isaac Morley and J.B. Stilley made as mid-19th century municipal engineers have been lost in the mists of time. But we do know they made history.

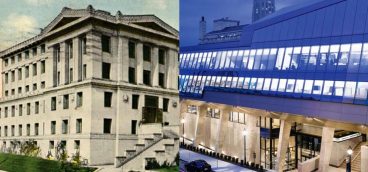

In April 1846, the pair received the first two engineering degrees from the Western University of Pennsylvania, later the University of Pittsburgh. In 2021, the Swanson School of Engineering, as the school is now known, is celebrating its 175th anniversary, and it’s come a long way from that inaugural class of two.

Through its history, Swanson — it became that to honor a 2008 gift of $41.3 million from alum John A. Swanson, founder of ANSYS, Inc. — has conferred so many degrees through its eight departments that it boasts nearly 30,000 living alumni. Perhaps more important than those numbers is the impact that talent has made on the region, the country and the world.

Dr. James R. Martin II, current dean of engineering for Swanson, says it’s no surprise that the school emerged as a leading engineering institution from its modest beginnings.

“Our engineering school was developed in the first place in response to the Industrial Age. The epicenter was largely here in Pittsburgh, which had the raw materials, the ability to transport heavy loads, and people coming here from all over the world. Our school was in response to the need to understand how we could have a structured approach and to understand things like metallurgy and how to capture energy out of the ground. The innovation that happened here set the foundations of the Industrial Age that allowed our country to prosper. That’s probably our biggest accomplishment.”

Pitt’s engineering’s expansion didn’t happen all at once. As new needs arose, its curriculum grew. The departments of Civil Engineering and Mechanical Engineering debuted in 1868, soon to be followed by Mining Engineering (1869), Electrical Engineering (1892) and Metallurgical Engineering (1909). In 1910, the school introduced the world’s first Department of Petroleum Engineering.

During this rapid growth spurt, Swanson got an important boost from the Mellon Institute, which founded departments of Chemical Engineering and Industrial Engineering that were folded in in 1919 and 1921, respectively. Later additions would be Environmental Engineering (1969) and Bioengineering (1998).

Curriculum diversity has been a key factor in Swanson’s impact, allowing it to tread where more narrowly focused institutions could not. In 1952, for example, Swanson launched an initiative that would evolve into the Undergraduate Cooperative Program with Industry, a pioneering co-op effort that provided quick career paths for students and well-trained new hires for industry. In 1961, Prof. Norman Wackenhut of the Mechanical Engineering Department collaborated with Dr. George Magovern, professor of surgery in Pitt’s Department of Medicine, on development of a mechanical heart.

Swanson’s reach has been international as well, particularly with the 2013 creation of a joint venture with Sichuan University of China. Through the Sichuan University-Pittsburgh Institute, Pitt became one of only five U.S. universities — Carnegie Mellon University is another — with large-scale partnerships with counterparts in China.

Yet perhaps Swanson’s greatest impact came during the world wars when it retargeted its expertise for rapid-fire training of troops. In 1917, Pitt established a reserve corps for engineering, mining and chemistry students, creating Camp Hamilton in the Allegheny Mountains for enlistees. Later, a detachment of 326 soldiers from Minnesota arrived on campus for training in auto mechanics and sheet metal technology, useful battlefield skills. Over the course of the war, that number swelled to more than 2,200.

Swanson’s role in World War II went farther, as more than 25,000 men and women participated in Engineering, Science and Management Defense Training courses sponsored by the U.S. Office of Education. That total placed Swanson in the nation’s top five engineering schools for this particular mission, which featured tuition-free, non-credit, mostly evening courses to attract local workers.

“A lot of the steel used in those wars went over the Hot Metal Bridge,” Martin says. “Our industrial strength won those wars, and we were a pivotal player in both wars.”

During WWII, Swanson adopted a year-round academic calendar to help students finish their studies — and deploy to the battlefield — more quickly.

Swanson used its expertise to help the U.S. Armed Forces with specific, sometimes deadly, problems. The U.S. Navy, for instance, asked the Department of Metallurgical Engineering to determine why so many of the Navy’s 20-mm and 40-mm anti-aircraft projectiles were exploding prematurely in loading plants and guns, killing U.S. personnel. A Swanson team suggested a fix, which was implemented before the war ended.

Today Swanson is focusing particularly on broader diversity, and it’s done particularly well attracting women. According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, in 2016-2017, Swanson conferred 29.5 percent of its undergraduate degrees on women, ranking it fourth among all U.S. engineering schools. “As engineers, we provide solutions that advance society,” Martin says. “That ultimately is what we are about. With the challenges we have now, such as climate change and COVID, we need a broader group of stakeholders in the workforce to be able to solve all those grand challenges. Our people need to know more than the traditional technical skills. They need to be comfortable working in teams, working with people from different cultures. They need to be comfortable working in that environment to maximize human potential.”

Thus, the school’s vision for the future, embodied in a document titled Engineering the Future, calls for diversity across a broad professional and personal front. Swanson, for example, seeks to partner with corporations and governments to solve the world’s most pressing concerns. To that end, Swanson will encourage its undergraduates to pursue double majors so that they can apply engineering skills across a multidisciplinary front.

“Think about how much of engineering is related to public health,” Martin says. “Engineering can be a great core degree for business, law and medicine.”

To encourage more lower income students, Swanson is waiving its $55 application fee through 2023. Finally, the school will strengthen its recruiting efforts in rural areas and expand its admission criteria to reduce reliance on standardized tests. Last year, Swanson rolled out a pilot program that adds personal interviews as admissions criteria.

“We were looking for a kid with more grit, who had know-how, who knew who to overcome adversity, not necessarily a kid with a perfect SAT score,” said Mary Besterfield-Sacre, Swanson’s associate dean for academic affairs, and director of the Engineering Education Research Center.

In all, 64 applicants were granted such interviews; 51 were accepted and 21, students who likely would have been rejected on the basis of their test scores, eventually enrolled. According to Besterfield-Sacre, the pilot is continuing this year. “We’ll do it again and figure out what it will take to really scale it up. We might have found a better way to find the right student.”

As a high school student, Anaya B. Joynes was leaning toward engineering when a Widener University conference on women in engineering exposed possibilities she’d never considered. “They talked about things like the water management profession,” the Philadelphia native recalls. “I hadn’t heard of that before. I learned how broad and vast engineering is.”

But it was a Pitt program that pointed her to Swanson. Called EXCEL, the initiative offers tools to ease the transition to college, including tutoring, peer mentoring and a two-week STEM summer bridge institute. As an African American woman, Joynes is a member of two minorities traditionally under-represented in engineering; she acknowledges the stress that can create. “There’s extra pressure to make sure I’m representing my race and my gender well,” said the senior who is president of Pitt’s chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers. “But I already knew I would have to do that in the real world, so this is kind of like practice.”

Having women exceed the national average in Swanson’s faculty helps, according to civil engineering professor Melissa Bilec. “It shows what diverse leadership could look like — that’s important.”

While working with the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh, Bilec worked on transforming Pittsburgh’s Hot Metal Bridge to a pedestrian/vehicular thoroughfare. The experience helped her define her specialty and goals.

“That spurred my thinking in repurposing infrastructure,” she says. “I always tell my students that one of the biggest contributors to climate change is the built environment — buildings, roads, bridges — and the materials used to build them as well as the production of those materials. The good news is that we can be a big part of solutions in the future.”

To that end, Bilec and colleague Anne Robertson developed a course exploring how the study of Renaissance architecture and construction may help us modify our own approach to the built environment, a course they’ll teach in Florence through the auspices of CAPA: The Global Education Network. Swanson has championed her outside-the-classroom ambitions, including her position as co-director of Pitt’s Mascaro Center for Sustainable Innovation.

“If I have a good idea or something I passionately I want to pursue, I’ve always been supported here,” Bilec says. “I can’t say that about other places.”

For her part, Joynes says that the vision from Swanson’s female faculty has encouraged her to develop her own. “It helps me see that if she made it through, I can do the same,” she says. “It also helps bring diversity of experience, which is very important because everything we do as engineers affects society. I don’t want to be just ‘book smart.’ I want to be the best holistic engineer.”