without a doubt, the course of my life was determined largely by my upbringing. My mother died when I was 6, and while my father was still around, my brother, Robert, and I were taken into the care of our mother’s parents and they raised us, with significant help from my mother’s aunt.

My mother’s parents, particularly my grandfather, were interested in song and poetry and, as she grew, my mother became interested in those things, too. She liked to sing, and often did, especially with my grandfather. In our home, the grown-ups would also, at times, speak rather poetically, usually in Arabic, a language that I did not understand. But when I listened, even as a small child, I knew that I was hearing thoughts and feelings expressed in a mode of speech that was above the normal.

My dad was Assyrian, a descendant from the oldest race of people in the Middle East. His father moved from Mosul, in what is now Iraq, to Jerusalem, where my father was born. At about 14, my dad emigrated with his brothers, via Mexico, to Pittsburgh where, uneducated but resourceful, he became a merchant of Oriental rugs and linens. He made it his business to know people who appreciated such fine goods, from Upstate New York to Florida, and made a good living selling his wares to those who could afford them.

My mother’s father was Lebanese and fled his homeland at a time when the Ottoman Empire was conscripting young Christian men into the police force to do its dirty work while they ruled. He refused to comply with the conscription and was smuggled out, emigrating, via Marseilles, to New York, and then to Maine. From there, he relocated to a small Lebanese community in Pittsburgh and established a business making covers for mattresses. Several years later, he brought his mother, his brothers, his wife, his son and his daughter (my mother), to join him. His father chose to stay behind.

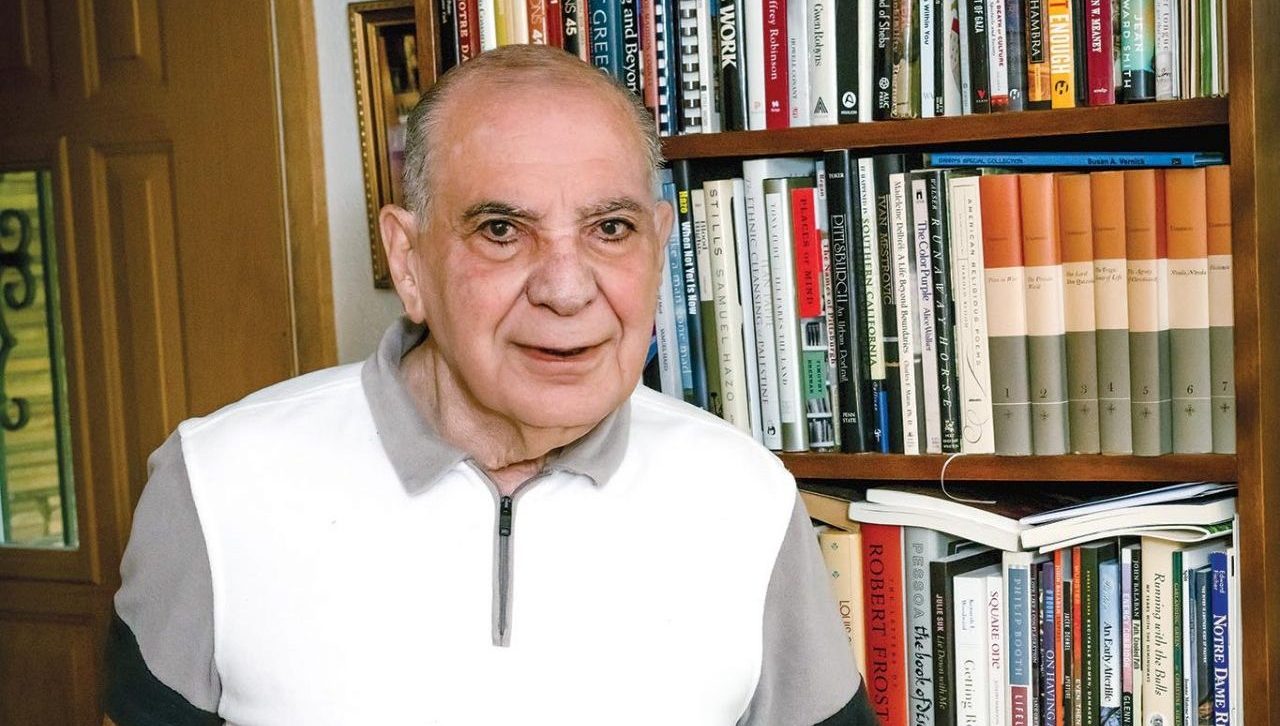

Sam Hazo

- International Poetry Forum, founder and director (1966- 2009)

- Honorary doctorate recipient, Notre Dame University (2008), and 11 other institutions

- Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, first poet laureate (1993- 2003)

- Duquesne University, McAnulty Distinguished Professor of English, emeritus (1955-1998)

- United States Marine Corps, Captain, regular and reserve (1950-57)

- University of Notre Dame, B.A., English literature (1949)

Upon arrival in America, my mother taught herself to speak and write English. And while her formal education ended with elementary school, it was obvious to all that she was very bright. Before long, the pastor of Epiphany Church asked my mother if she would be a teacher for immigrant children who did not know English and she obliged. A few years later, she also became a nurse for a Greek physician, whose patients mostly spoke only Greek. To serve them better, my mother taught herself conversational Greek, adding it to the two other languages she spoke: Arabic and English.

As I said, at an early age, I became aware that a mode of communication existed that rose above that of mere conversation, and that stuck with me. In 1945, a doctor in Pittsburgh named Leo D. O’Donnell provided a scholarship for me to attend Notre Dame University. (He liked to keep a boy there because he was an alumnus.) My tuition, at that time, was $375 per semester. That included tuition, room, board, books and laundry. Even adjusted for inflation, that sum is unbelievably low. In the ‘40s, the cost of a first-rate education was $750 per year.

Initially, I was inclined to be a lawyer. Thank God I decided against that. But I decided to major in English literature, for which I had a great teacher named Frank O’Malley. He introduced us to not only English and American literature, but to continental literature as well, the latter of which focused on literary movements such as humanism, existentialism, and absurdism in modern European literature, mainly fiction, with special attention paid to key literary figures such as Albert Camus and Frantz Kafka. Professor O’Malley also taught us that serious writing had to have a moral and even a theological dimension. When one reads literature, it is important to deduce the author’s concept of mankind. What evocation of the nature of man is coming through? Are we just beasts on the prowl? Or are we morally and ethically sound?

In our coursework, we read Graham Greene, French translations of François Mauriac and Ignazio Silone, and other political writers from Italy and France. Particularly, I read the works of French philosopher Jacques Maritain. Years later, when I was working on my doctorate, I asked if I could do my dissertation on the aesthetic of Maritain. The English Department gave me the go-ahead, so I wrote it, and had occasion to meet Maritain when he was teaching at Princeton. I left him a copy of my manuscript and, to my surprise, he wrote an introduction to it. Three or four years ago, someone at the Franciscan University Press heard about that manuscript and asked to see it. I sent it to them, along with Maritain’s introduction, and it was published — after 60 years!

In 1949, I graduated from Notre Dame with a degree in English literature. I returned home and got a job as a reporter at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, having been hired by a man there named Joseph Shuman, who was an excellent editor. Shortly thereafter, however, Joe was succeeded by a fellow named Frank Matthews, with whom I did not get along, and I was fired from the paper after six months. That shook me up — so much so that, believe it or not, I went to work on a farm in Herman, Pennsylvania, in Butler County.

In 1950, the Korean War broke out. I enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps and went through boot camp and all that, after which half of my battalion was sent to Korea. I was dispatched, however, to Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia to work at an Air Force Station. I was commissioned as a lieutenant, and went to what was then called “Platoon Leaders Class,” which was basically just infantry training. After that, I thought, “This is it. I’m off to Korea.” Instead, I was sent to a post in Portsmouth, Virginia, as a legal officer.

Looking back, I learned some valuable lessons during my time in the service, one of which was this: Never choose a profession that is based on total obedience. I don’t care if it’s the military or a church, the government or a business, there must be room for dissent. In life, you may find yourself, at some point, in a position of duty to someone for whom you have no respect and that could compromise you, completely. The punishments for disobedience may vary, but they all amount to the same things: unfavorable discharge, court martial, excommunication, pay reduction, or firing — all in an attempt to silence and dominate you.

For a time at Portsmouth, there was a colonel named Harlan Cooper and, one day, I asked him, “Sir, may we organize a football team here?” I thought it would be fun, a morale booster. Well, he proceeded to ask me all kinds of questions about this and, finally, when he learned where I went to college, he said, “So, you’re from Notre Dame. Well then, you must know something about football.”

With Cooper’s permission, we scheduled several games and played against some Navy teams, losing the first five, but winning the sixth. Once the “season” was over, I went to Col. Cooper again and asked, “Would it be possible to have a dinner for the team at the Officers’ Club?” He said, “Sure. Just tell the ‘niggers’ not to come.” I said, “Sir, I can’t do that.” Consequently, I was relieved of my position as a legal officer and spent my last two months in the Marine Corps doing crap jobs on the base. The only thing that pleased me during that time was when Col. Cooper asked each of the 23 white men who played on the football team to come to dinner at the Officers’ Club, and they all turned him down, to his face.

When I was discharged from the Marines, I went down to register with the Veterans Administration and a fellow there asked me, “Do you want to sign up for the G.I. Bill?” I said, “No. I went to college before I joined the service.” Then he said, “I don’t mean undergraduate school. The G.I. Bill offers you four years of education. It doesn’t matter whether it’s undergraduate or graduate.” So, I said, “OK. Put me down. I’ll go for an M.A.,” to which he replied, “Look, I’m going to put you down for a Ph.D. because, if I don’t, and you decide later that you want to do it, they won’t cover it.” So, thanks to the G.I. Bill, I enrolled in graduate school and, in time, got an M.A. at Duquesne and a Ph.D. at Pitt. My dissertation was in literary theory.

Just like in the service, in grad school, I learned some important things, one of which was that it has nothing on undergraduate education. Later on, having earned my doctorate, I was teaching at Duquesne and was, from time to time, asked to teach a graduate-level course. Of course, I was willing. But mostly, I preferred teaching at the undergraduate level because that’s where education really happens. Graduate education is so specialized that nobody really learns anything. The students simply absorb enough information to pass their exams, and that’s it.

In my opinion, much of the problem with higher education is that the only reason some people go to college is to get a degree so they can get a job. Then they get that job and, sure enough, life happens, and they reach retirement age. Heaven to them is going to Florida for the winter. Why? Because there’s nothing they love to do. They live idly for about five years and then they die, out of boredom, I guess.

So, here I am today, safely ensconced in my hometown. And when it comes to “livability,” I’ll take Pittsburgh over any city anywhere, any day in the week. There’s something about Pittsburgh that feels permanent, but I can’t tell you what it is. One day, I stopped a fellow to ask for directions. He looked at me and asked, “Are you from here?” I said, “Yes.” Then he asked, “Do you know where such and such is?” I said, “No,” to which he responded, “Come with me. I’ll show you.” That doesn’t happen in many places.

Rand McNally once touted something called “The Most Livable Cities Graph” and Pittsburgh was ranked second only to Dade County, Florida, as having the oldest population in the country. Some said this was because people like it here so much that they stay forever. But that’s not the reason. A lot of people in their 20s and 30s go somewhere else to work and many of them, when they begin to have children or finally decide to retire, come back here. Many even choose to live in the neighborhoods in which they were raised, and are happy to grow old here. That’s why the age of Pittsburgh’s population remains so high.

My wife, Mary Anne, and I had been married for 10 years and wanted to have children, but with no luck. During those years, we went to see a series of doctors, none of whom could find anything wrong. Finally, one of them said, “I don’t know. Maybe you should think about adopting.” Well, Mary Anne was all for that, but I said, “No, honey. Let’s wait another year.”

Around that time, I got a call from the U.S. State Department asking, “If you’re free in February, would you like to go to Jamaica and represent the U.S. for ‘Literature Week’?” I’d done one other stint for the State Department, so I said, “OK.” At the time, Mary Anne had the flu, but her doctor said, “Take her down there, Sam, because the weather in Jamaica in February is beautiful. It will do her good.” So, we went.

As fate would have it, we got to Jamaica on the same day that Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip arrived for an official visit and, as a result, the Literature Week schedule was cleared for about five days. What did we do? We decided to take a vacation — and that vacation had consequences.

When we returned home, after about a month, Mary Anne said, “Sam, I don’t feel well.” So, I called a doctor friend of mine, who said, “Get me a specimen and I’ll let you know the results on Monday.” So, he called, just as he said he would, and told me, “Sam, Mary Anne’s not only pregnant; she’s been pregnant for about a month and a half. Take her to her doctor, just to make sure, because you’re both in your late 30s now and you’ll have to proceed carefully.”

Mary Anne was, in those days, the secretary for a legal office downtown, so I went there. When I got to her, she looked at me and asked, “What’s wrong?” I said, “Nothing. But you better keep the middle of November free.” “Why?” she asked. “Because you’re going to have a baby.”

Of course, I purchased all of Dr. Spock’s books on the way home and, that evening, we went out for dinner. When next we saw Mary Anne’s doctor, he told her, “I want you in bed for a week.” And when she finally got up, she had never felt better in her life, and that continued throughout her pregnancy. She had the baby with no problem — a wonderful son who has gone on to build a good family of his own, for which I’m very grateful.

I’m now 94 and, the only way to explain that is, I’ve been lucky. To be honest, I don’t feel much different today than I did when I was 40, 60 or 80. But I have found that living, sometimes, is much harder than not living. When Mary Anne took ill, I was in my 80s and, during her illness, I didn’t pay any attention to my age because I was focused on making sure that she was cared for. She had dementia, with a slow and, fortunately, merciful decline. Nevertheless, it was murderous to see such a lovely, intelligent woman gradually lose touch. She died in 2016.

In the Hazo family, we have only one rule for living: “No matter what you do, make sure you love to do it.” In other words, choose what you love to do, no matter what it takes, and there’s no way you’ll end up miserable. Maybe you’ll have it hard here and there but, eventually, things will work out for the best.

My son, Samuel Robert, first taught music in high school, and then in college, and was a band director. At some point along the way, he started composing. Now, his music is being played all around the world. In fact, on the internet, you can see and hear performances of his music in Japan, Australia, Eastern and Western Europe, and Brazil. My son had the courage to follow his passion and that has made all the difference. When you’re a writer, like me, or a composer like my son, you never have to retire because you don’t really have a job. You have something better. You have a vocation and, as a result, you will always be OK.

Throughout my writing career, I’ve been, at various times, a poet, essayist, playwright and novelist, as well as an editor, translator and critic. I’ve authored dozens of books and received my share of accolades. About a year or so ago, I was on a plane and this other fellow had the window seat. When I sat down next to him, he looked at me and said, “My line is shoes; what’s yours?” I said, “I’m a writer,” and he didn’t seem the least bit impressed. “Well, what do you write?” he continued. I said, “I don’t really know what it is until I’ve written it.” And he pressed on. “So, where are you going now?” I replied, “I’ve been invited to a university to recite my poems.” With a look of incredulity, he responded, “And they pay you for that?”