Then and Now

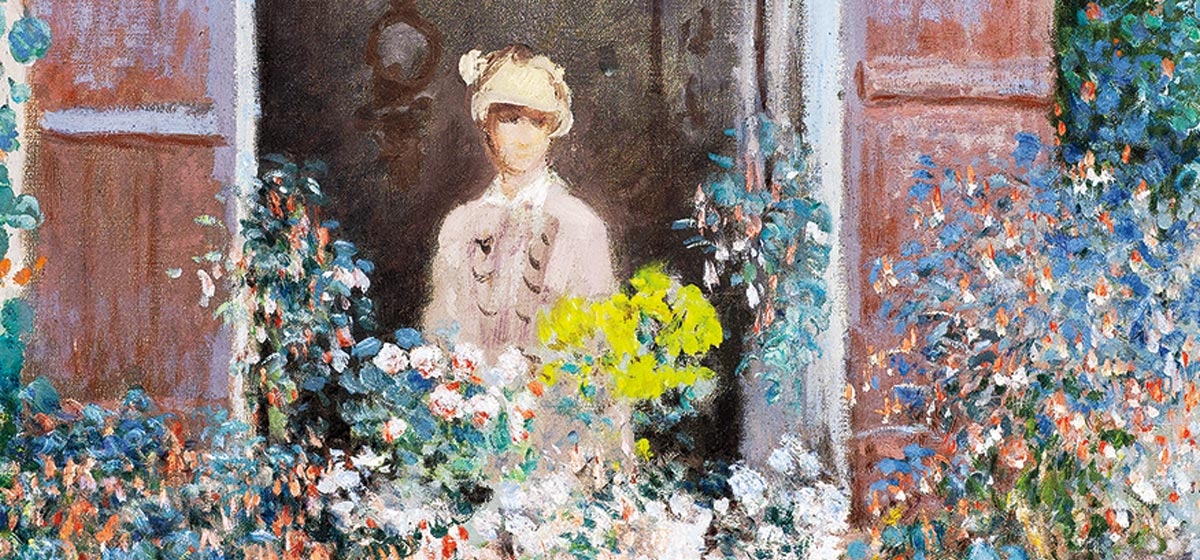

After a foray into fashion, The Frick Art and Historical Center has returned to its comfort zone with “Van Gogh, Monet, Degas: The Mellon Collection of French Art from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts” (March 17-July 8, 2018).

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”136″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon amassed an extremely large collection of art, and while he was most interested in British art, they also bought a lot of French art. They had an affinity for Edgar Degas, giving over 100 pieces, primarily sculptural studies and drawings to the National Gallery of Art (NGA). In this show, Degas’ small racetrack scenes and the intimate scene in a millinery shop reveal his ability to animate an ordinary activity by experimenting with spatial shifts, moving to the flatness that would characterize modern art.

The star of the show is sure to be “The Little Dancer” by Degas, which has captured hearts for over a century, though its initial reception was rather cool with viewers expecting ethereal beauty, not a realistic depiction of a 14-year-old girl. The original, given to the NGA by the Mellons, was the only sculpture exhibited during the artist’s lifetime because he tended to experiment with movement in his sculptures, using them as studies for other works. The original was in wax, with this bronze being one of many cast after his death, but it hints at the textured surface of the original. It’s quite unusual as Degas dressed his work in real clothes and human hair that he covered with a layer of wax, except for the tutu.

The show includes all the major French artists, but it rounds out the usual suspects with lesser known artists, those working before and after impressionism, and unusual works by major painters. Particularly interesting is a small group of interiors that span from Monet to Matisse to Picasso. Gauguin, known for his Breton landscapes and Tahitian scenes, is here with an atypical still life, while Manet and Morisot, both figurative artists, are represented with beach scenes. This variety allows a look at the edges of such a popular movement.

Paul Mellon, the son of NGA founder Andrew Mellon, left Pittsburgh for Virginia horse country, and his enormous collection went to his favorite museums elsewhere. Over 1,000 pieces went to the NGA, a much smaller number to the Virginia museum, and he established the Yale Center for British Art and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art in London. He and his sister Ailsa Mellon Bruce, a patron of the Carnegie, did combine their foundations into one, which partially endowed the Carnegie International and commissioned the report on the International that led to the move to one-person shows in 1977 and ’79.

It’s inevitable to compare this collection to the Carnegie’s impressionist holdings bought by Sarah Mellon Scaife. Unlike the Cone sisters of Baltimore who were buying early on and who put together a phenomenal group of works, the Mellon cousins entered the market much later, leading to idiosyncratic collections. It would have been wonderful to see the two collections together as they complement each other in a way that gives a much fuller look at the nuances of the impressionist moment, looking at both the stars and the outliers, the icons and the rarely seen work, thus broadening our understanding of that popular period.

Five local photographers showcase immigration issues

If you missed the photographs about immigration at the Jewish Community Center’s American Jewish Museum this fall, you can still see them at the Westmoreland Museum of American Art in Greensburg through April 22.

The brainchild of Brian Cohen’s umbrella organization The Documentary Works, this exhibition features the work of five Pittsburgh photographers, Brian Cohen, Scott Goldsmith, Nate Guidry, Lynn Johnson, and Annie O’Neill, who document stories about contemporary emigrés in a city known for its large immigrant population.

As Cohen wrote, “Working with the premise that ‘we all come from somewhere,’ the group explores the central role that immigration and migration have played, and continue to play, in the formation of our identity and culture, and in sustaining our economy, and in so doing, aims to create a space for civil, constructive conversation about belonging and cultural heritage today.”

The show gives viewers a look at one aspect of social justice in our city. To understand the relationship between art and social justice, I turned to Melissa Hiller who, as the director of the American Jewish Museum, has furthered their mission with thoughtful exhibitions and programs concerning the issues of our times.

Q. Why did this show appeal to you?

A. The photographs were made by some of the city’s most talented documentary photographers. The photos are evocative and thoughtful, and merit being exhibited in a gallery setting. I knew the show would create pathways for us to create public programs that explore the current, and frankly, divisive questions around immigration, Americanism, and who belongs. The JCC was founded in 1895 as a settlement house in the Hill District. Our roots remain connected to settlement house ideals, so we have a stake in talking about issues that affect communities. It also appealed to me that when Brian conceived this project he hoped it would travel to venues like the Westmoreland. When you finish reading a good book, you want everyone you know to read it, and I feel that way about this project. Every museum has opportunities to make this project their own, and to connect the work to their own stories, to their visitors’ stories, and even to their own collections.

Q. As a child of the Sixties, our generation felt we could change the world through protests. Art didn’t play as large a role then. Today artists talk about affecting social change and transformative art and engaging the larger community about social justice. What’s different now?

A. I think the strict rules throughout history that governed the ideas around what art is and who artists are have completely transformed, and much of that transformation occurred in the 1960s. In many ways, artists are actually the most suited for instigating change or awakening us to different realities because they make it possible to imagine what change looks like, sounds like, and feels like.

Q. What is the relationship between art and social justice?

A. Creative expression moves us in the soul and hits us in the gut, so artists have this unparalleled power to strip away facades and help us to see, hear, and feel other perspectives and other people’s stories and challenges. Art and humanities are very often the root system of how we find common ground, build empathy, see other sides of the coin, and connect value to people who are different from us. For this, I think artists are really patriots.