The Steelers’ First Great Rivalry: Those Bloodbaths with the Eagles

In 1933, Art Rooney, in anticipation of the elimination of Pennsylvania’s Blue Law banning professional sports from playing on Sunday, paid $2,500 of his racetrack winnings to purchase an NFL franchise for the city of Pittsburgh. Across the state, Philadelphia native Bert Bell, partnering with his friend Lud Wray, paid $2,500 for a defunct NFL franchise to bring the NFL to his home town. Eventually Bell bought out Wray and became sole owner of the Eagles.

The two franchises, the first in Pennsylvania since the birth of the NFL in 1920, should have been natural rivals, but they were so awful for years that their only competition was for last place in their division. The Steelers were so bad that in 1941 Rooney, who, critics claimed, was more interested in local politics and horse racing, did the unthinkable and sold his struggling franchise to Boston playboy, Alexis Thompson, who operated out of New York.

While Rooney was roundly condemned, the deal was actually the beginning of an ownership swap. After selling his franchise to Thompson, Rooney, with half of the money from the sale, bought a major interest in the Philadelphia franchise and became co-owners with Bell. Rooney and Bell then proposed a franchise swap to Thompson, who wanted a team closer to New York. When Thompson agreed, a relieved Rooney had his Pittsburgh franchise back, though only as co-owner.

In 1943, the relationship between the Steelers and the Eagles took another odd twist because of the impact of World War II on professional football. The Steelers lost so many players to military service that they didn’t have enough to fill their roster. A desperate Rooney and Bell contacted Thomas, the Eagles’ owner, who was also short of players. The Steelers and Eagles agreed to combine their rosters and formed what became known as the Steagles. Despite divided loyalties, the hybrid team managed to finish with a winning record at 5-4-1.

After the end of the war, the NFL, faced with a professional football rival in the newly formed All-American Football Conference (AAFC), asked the experienced Bert Bell to become its commissioner. When Bell agreed, Rooney bought out Bell’s interest in the Steelers and, once again, became sole owner.

Another move by Rooney, the hiring of former Pitt coach John “Jock” Sutherland, finally turned the Steelers into contenders. In 1947, they played their way to an 8-4 record and a tie with an improved Eagles team for the division title. Before the playoff game at Forbes Field, Rooney was delighted. He claimed that, after years of losing, he found it strange to be a winner: “It’s a great feeling not having to duck down the side streets.”

Unfortunately for Rooney, his team played like the Same Old Steelers and lost the playoff game, 21-0, to the Eagles. That spring, the Steelers suffered another grievous loss when Jock Sutherland collapsed and was rushed to a Pittsburgh hospital where doctors discovered that he had a brain tumor. He died on April 14, 1948, two days after surgery to remove the malignancy.

The 1947 season proved a turning point for the Steelers and Eagles. After losing to the Chicago Cardinals in the NFL championship game, the Eagles went on to win NFL championships in 1948 and 1949. Their reign over the NFL ended only when the powerful Cleveland Browns entered the NFL in 1950 after the collapse of the AAFC.

The Steelers, after hiring Sutherland assistant John Michelosen, struggled to win games, while developing a reputation, even as they were losing games, as one of the toughest teams in the NFL. That was especially true in their games against the Eagles. While the Eagles dominated the Steelers on the scoreboard, winning ten of twelve games from 1948 to 1953, the games on the field were grudge matches, featured by flying elbows and broken jaws. The Steelers Jack Butler said that it was like “going to war.”

The games led to so many cheap shots and injuries that Commissioner Bert Bell warned the Steelers and Eagles, that “any use of the forearms, elbows, or knees and any striking of an opponent shall be penalized and the player disqualified.” The warning was ignored by both teams, especially enforcers like the Steelers Ernie Stautner and the Eagles Norm “Wild Man” Willey.

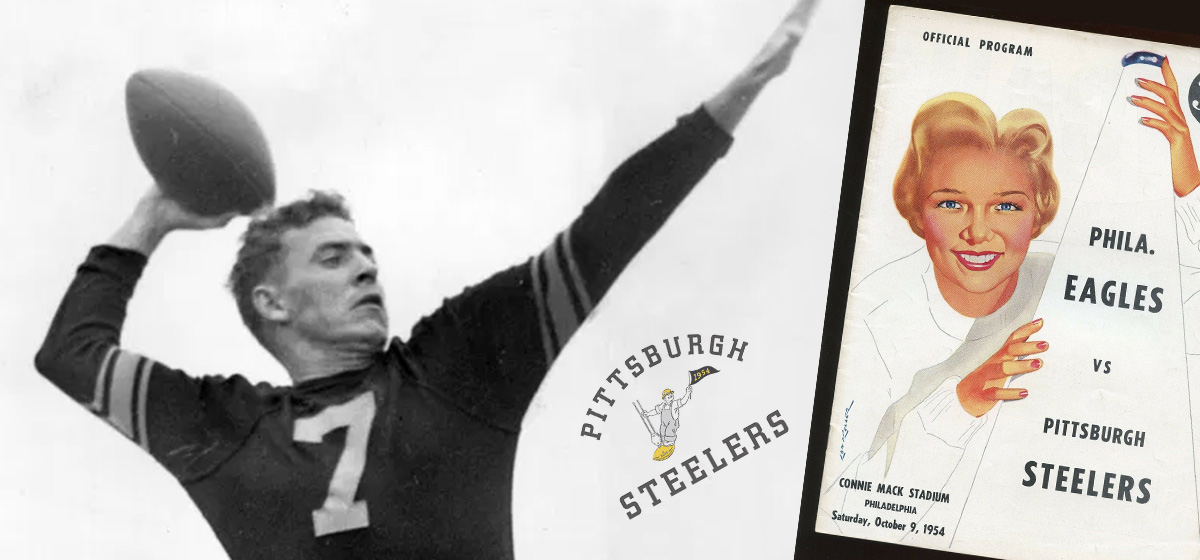

The rivalry reached a climax on Saturday night, October 23, 1954 when the Steelers played the Eagles at a sold-out Forbes Field in arguably the greatest game to that point in Steelers’ history—and it also featured a miraculous catch. Late in the game, with the Steelers clinging to a 10-7 lead, Quarterback Jim Finks, playing with a catcher’s mask attached to his helmet to protect a broken jaw that he had suffered in an earlier game, lofted a pass just as he was hit in the jaw by an Eagles defender.

The wobbly pass should have been intercepted, but Elbie Nickel, who had earlier caught a 53-yard touchdown pass from Finks to give the Steelers a 10-0 lead, leaped between two defenders, tipped the ball into the air, and caught it as he fell to the ground. Three plays later, the Steelers scored on a Lynn Chadnois five-yard run and went on to a dramatic 17-7 victory.

The win gave the Steelers a 4-1 record and a tie for the division lead with the Eagles, but so many players limped or were carried off the field that the Steelers never recovered. They ended the season with a losing record. The battered Eagles never bounced back from their injuries and also fell out of first place.

The dramatic and brutal game was so decimating that it brought the grudge matches between the Steelers and Eagles to an end. There would be other rivalries for the Steelers, especially their on-going turnpike rivalry with the Cleveland Browns, but none as ferocious and bitter as their blood baths with the Eagles in the early 1950s.