The Book on Pittsburgh

Wherever Stefan Lorant went in his life – whatever job he held, whatever town he lived in, whatever nation – he had a remarkable knack for being in the right place and for sniffing out who the most important people were and meeting and befriending them.

Previously in this series: Stefan Lorant, Part I

In Germany, as an outsider from Hungary, Lorant gave Marlene Dietrich her first screen test (she failed miserably), made a lifelong friend of Greta Garbo, dated Leni Riefenstahl, traveled on diplomatic trips with Weimar Chancellor Heinrich Brüning – bizarrely, I used to run into Brüning in Hanover, New Hampshire – and often chatted up Adolph Hitler in cafes in Berlin.

In England, despite speaking little English, Lorant lunched with Prime Minister Ramsay McDonald at Chequers, with Churchill (also at Chequers), and lunched with Joseph P. Kennedy while the latter was Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s.

All his adult life Lorant was fascinated by the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in America. What attracted Pittsburgh to him, Lorant told me, was “the damned brawn of the place.”

Yes, Germany (Lorant’s first adopted country) had the Ruhr Valley – at least, they had it after Hitler brazenly took it back in 1936 – with its coal and steel production. And England (Lorant’s second adopted country) had its Manchester (steel) and New Castle (coal).

“But Pittsburgh,” Lorant said, “had it all and much more besides.” And it was true. Pittsburgh had steel (the United States Steel Corporation, then the world’s largest company), coal (Consolidation Coal Co., the largest coal producer in America), aluminum (Alcoa, the world’s largest aluminum maker), glass (Pittsburgh Plate Glass, or PPG, the nation’s largest glass producer), electrical equipment (Westinghouse), prepared food (Heinz), oil (Gulf Oil, one of the famous Seven Sisters), banking (Mellon and PNC), diversified manufacturing (Rockwell), and so on.

But being fascinated by Pittsburgh didn’t extend to actually wanting to visit the place, because Pittsburgh had paid an enormous price for its brawn. By the 1940s the city was arguably the most polluted town in the world. Simply living in Pittsburgh was the equivalent of smoking two packs of unfiltered cigarettes a day. The clouds of pollution were so thick the streetlights had to be turned on at 10 o’clock in the morning, and men had to change their detachable collars at lunchtime.

But after World War II ended, Pittsburgh began to clean up its act. The unlikely duo of Richard King Mellon, head of the Mellon family, and Mayor David L. Lawrence, head of the Democratic Party, banded together to create the original “Pittsburgh Renaissance” – not to be confused with the city’s later “Renaissance II,” beginning with the collapse of the steel industry in the early 1980s, or the recent “Renaissance III,” as the city converted itself into a tech hub focused on artificial intelligence, robotics, autonomous vehicles, and cutting edge healthcare. (Pittsburgh is very into reinventing itself.)

Under Mellon and Lawrence, smoke control and urban renewal transformed the face of the city. Vast swaths of land and buildings near the Point (where the Ohio River forms) were demolished, and the Lower Hill District, occupied mainly by African-Americans, was completely destroyed.

But now that Pittsburgh’s air could (almost) be breathed, Stefan Lorant decided the place might be worth a visit after all. And what he saw astonished him. Never before (according to Lorant) had a great city so completely reinvented itself. Pittsburgh was now worthy of being chronicled – by Lorant himself.

As he had done in Germany and then England, Lorant ingratiated himself with movers and shakers in Pittsburgh. He befriended Edgar Kaufmann, department store magnate and owner of what was then the most famous private home in America, Fallingwater. (Kaufmann encouraged Lorant to write about Pittsburgh.) He befriended Theodore L. (Ted) Hazlett Jr., who ran the A. W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust, which had helped spearhead the Renaissance. (Ted helped fund the Pittsburgh book.)

And Lorant befriended Ambassador Adolph W. Schmidt, who had managed Paul Mellon’s family office before becoming Ambassador to Canada. I later ran a different Mellon family office and “Schmitty” was an advisor and mentor to me. He told me many stories about Lorant and advised me to “keep your distance,” advice which, had I heeded it, would have made my life much smoother.

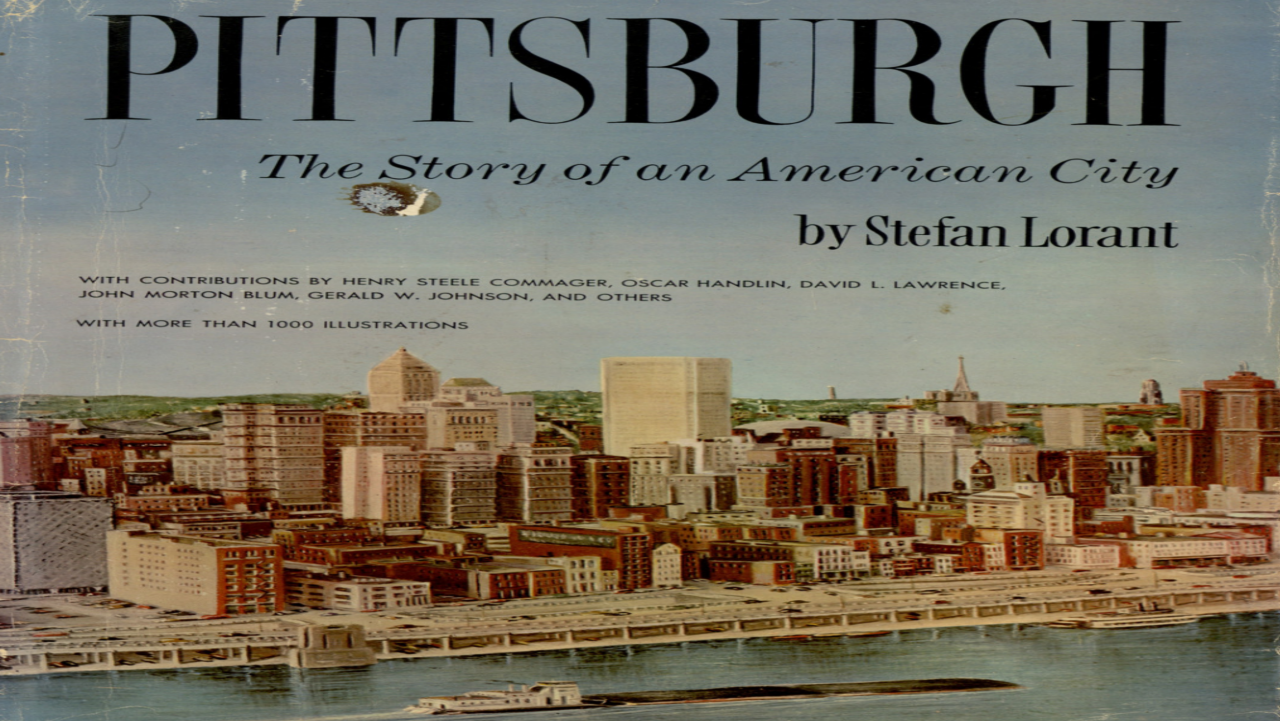

The ultimate result of Lorant’s labors was a book called Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City. The book appeared in 1964 and, despite being a more-or-less vanity project, proved to be both enormously popular and an instant classic. Lorant engaged famous historians to write some of the chapters (Henry Steele Commager, Oscar Handlin – Lorant had studied under Handlin at Harvard) and hired the best photographers in the world to photograph Pittsburgh for the book (Margaret Bourke-White, W. Eugene Smith).

The final book was a kind of “intellectual coffee table book” – 520 pages of sometimes erudite, sometimes silly text, and page after page of often brilliant, but occasionally almost offensive, photography (young women in very short skirts blowing in the wind).

Because Pittsburgh foundations had supported the cost of the book, the original photographs became the property of the City of Pittsburgh. These were ceremoniously delivered to the main branch of the Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood – the grandfather of all the Carnegie libraries.

Thereafter, every few years Lorant would produce a new edition of the Pittsburgh book, basically keeping all the original material but adding new material to bring the book up to date. As a result, the original 520 pages grew to 776 pages – the word “monumental” barely begins to describe it – and the book became too heavy for all but the most sturdy coffee tables.

At some point, this being in-between the fourth and fifth editions of the Pittsburgh book, I was introduced to Stefan Lorant by Bruce and Gail Campbell. Bruce had been the top aide to Pittsburgh mayor, Pete Flaherty, and in that capacity had come to know Lorant, who was now well up in years. Lorant had asked the Campbells to help produce the fifth edition of the Pittsburgh book.

Lorant was eager to publish the new edition while he was still alive. Since I was running a Mellon family office and was the president of the local foundation association, and since Lorant needed financial support, I somehow allowed myself to become involved, having forgotten Adolph Schmidt’s wise advice to keep my distance.

More on this next week.

Next up: Stefan Lorant, Part 3